On Nov. 17, North Cowichan began dismantling an encampment on Lewis Street — home to about 75 people — and transitioning residents to other sites around the municipality. The Cowichan Community Care Network, a local group made up of housed and unhoused individuals who meet regularly in the Lewis Street area, says decampment is putting residents at risk of violence and death.

The notice to vacate, distributed to Lewis Street residents on Friday, Nov. 14, lists three temporary sheltering sites. One on York Road north of the dike, another in the trees across from Home Hardware on Beverly Street and one near Paddle Road. Once the operation is complete, camping will no longer be permitted along the street, sidewalks or boulevards on Lewis Street.

The days following the dismantling of the encampment were also met with more than 80 overdoses in the region. Cowichan Community Care Network points to recent research that has shown a link between street sweeps and decampments and an increase in overdoses.

The Cowichan Community Care Network is concerned the sites lack adequate resources such as clean drinking water, hygiene and sanitation facilities, fire-safety equipment, waste-management services and access to harm-reduction or other social supports. They also warn the locations are prone to winter flooding.

The notice distributed to residents did not mention that any of these services would be available at or near the new sites and listed the “newly opened 24/7 shelter, located in the former Ramada Inn,” as an available shelter space — despite the shelter not yet being open.

John Horn, North Cowichan’s director of social planning and protective services, told The Discourse that staff had hoped the shelter — run by Lookout Housing and Health Society — would be operational this week, but an opening delay meant the notice falsely stated that the shelter was open.

A City of Duncan press release dated Nov. 14 stated the shelter would not open until “later next week”, which would have been around Nov. 22 or 23, as set-up was still underway.

“We recognize it’s only a 24-bed shelter and there’s probably 200 homeless folks with no place to live,” Horn said, adding that he hopes the new tenting sites selected by the municipality will have enough space to accommodate everyone from Lewis Street as they transition to other housing options.

While the municipality says it is providing some services at the sites, such as portable toilets and handwashing stations, the Cowichan Community Care Network says residents should have been treated as stakeholders.

“Consultation is key. Nobody was asked where they wanted to go or how much time they needed to make the move,” the group said.

In its notice, the municipality said it recognizes the removal of tents from Lewis Street must be balanced with the need for safe, accessible sheltering alternatives.

“The notice of decampment — which was the first most residents heard of it — was delivered less than one business day before the decampment, clearly demonstrating that the municipality has not engaged in any communication or consultation with residents,” the Network said in a statement.

Concerns over temporary shelter sites

While the municipality has designated three sites that could be used for temporary sheltering overnight, residents will still be obligated to take down their shelters in the morning.

A National Protocol for Homeless Encampments in Canada — created by the UN special rapporteur on the right to adequate housing — states that governments should provide people in encampments with access to clean water, sanitation facilities and heat as well as support services.

Horn told The Discourse the municipality would be providing portable toilets, hand wash stations, deliveries of bottled water, garbage removal and cleaning by municipal staff. Eventually, he said fire suppression equipment such as fire blankets would also be available, which would be provided through BC Housing.

The Network is concerned that there is not enough lighting and that the selected areas, being so close to wetlands, will be flooded in the winter. The area between Beverly Street and the dike is a well known wetland and has been highlighted as such in environmental assessments by the province.

“These are sites we’re quite familiar with, so we expect that they’ll be above the water tables throughout the winter, because that’s on the edge of the marsh,” Horn said.

Horn said the sites were chosen because they were close to street lights, but the Beverly site in particular is away from the road and in the trees which block light, according to the Cowichan Community Care Network. The site at the end of York Road does not have any streetlights in the area that is designated for setting up shelters.

“The ability to stick together in a well-lit public area allows residents a small measure of safety from the constant acts of violence from the public, which can become deadly for people who are isolated,” the Network said in a media release.

In a video obtained by The Discourse, Horn told a legal observer that they will be providing “a lot more services at the new sites than people get here.”

The Network says while different services may be available at those sites, they are concerned about the loss of access to services provided by the Warmland Shelter located on Lewis Street — such as laundry and meals — as well as the loss of access to harm reduction services at the Overdose Prevention Site.

“If they really were invested at all in the wellbeing of the people living on Lewis Street, they would have consulted with them, treated them as valuable human beings, and above all, they wouldn’t have displaced them before finding a real alternative to sleeping on the ground,” the Network said.

As of writing, there is currently one portable toilet and handwash station at each site but no evidence of garbage disposal services or bottled water.

“The sites are not suitable alternatives,” the group said.

A spike in overdoses

In the days following the decampment, the Cowichan Community Action Team reported that they have seen a spike in drug poisonings in Cowichan. Island Health also issued a drug poisoning overdose advisory for the region on Nov. 19.

The Canadian Mental Health Association: Cowichan Branch, said in a Facebook post that there have been more than 80 overdoses in the region in the past week and thanked the community for helping cover a Narcan shortage after a call-out was made to drop off Narcan at the shelter.

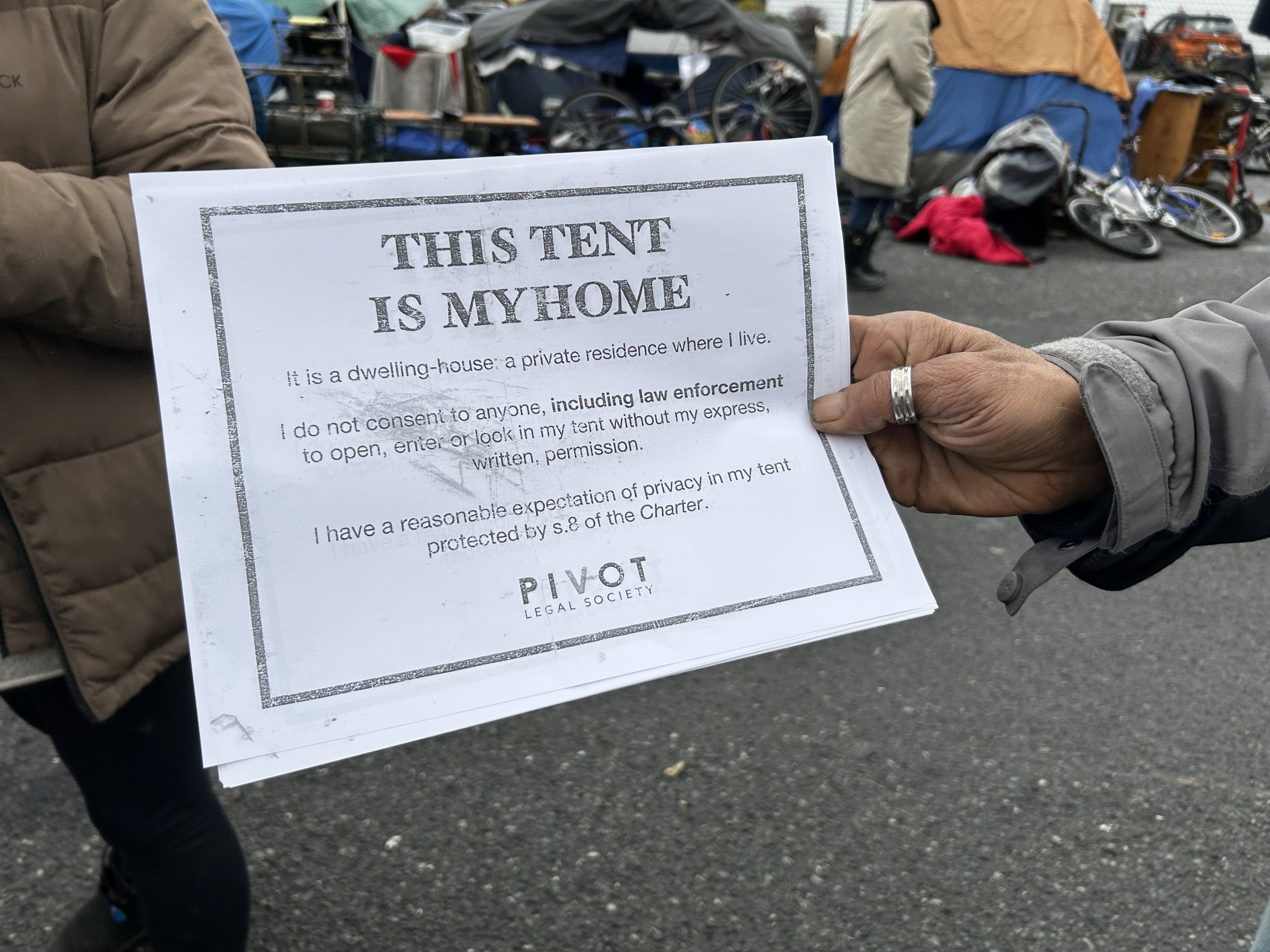

A recent study published in the journal Public Health — authored by researchers from Simon Fraser University, the B.C. Centre on Substance Use, Pivot Legal Society and others — found that street sweeps and confiscation of belongings in Vancouver was correlated with an increased risk of violence and overdose among unhoused individuals for up to six months afterward.

“The statistically significant association between non-fatal overdose and the confiscation of belongings among those reporting homelessness is of significant concern,” the study says.

A finding in the study also suggests that those whose belongings are confiscated from street sweeps could be forced into withdrawal or turn to different drug markets to replenish what was confiscated — markets where they may not have access to safer supply.

“With their belongings taken away, individuals may also feel an increased sense of desperation, distress and instability, potentially leading them to seek comfort in cheaper but more toxic drugs obtained from unfamiliar sources, thereby heightening their susceptibility to overdose,” the study says.

Speaking from Halifax, where she is participating in a federal conference on the opioid crisis, Duncan Mayor Michelle Staples said in a Facebook post that while she’s not “attempting to link” the decampment and recent sweep of Lewis Street with the spike in overdoses in the region, the increase in overdoses highlights how uncoordinated the response has been to the toxic drug crisis from higher levels of government.

“I am struck once again by the sheer reach of this crisis in communities of all sizes and the lack of coordination and will at higher levels of governments to treat this as an emergency,” she said.

Horn could not be reached for comment on the overdoses in time for publication. The Discourse has reached out and will update the article if a response is received.

What does procedural fairness look like?

Cowichan Community Care Network said North Cowichan’s actions do not ensure procedural fairness, as set out in Matsqui-Abbotsford Impact Society v. Abbotsford (City). It’s a court case that saw Justice Sandra Sukstorf rule that while the City of Abbotsford could dismantle an encampment occupying a public park and plaza, the city must respect the Charter rights of encampment occupants and mitigate harms faced by them.

The city was told by Sukstorf to implement a phased approach to relocating encampment residents and said their displacement “should only occur when adequate shelter options, including access to harm reduction services, are available.”

Sukstorf also included other conditions, one of them being that “encampment occupants receive proper notice and a meaningful opportunity to be heard,” so they could have their concerns addressed and express preferences for proximity to necessary services.

“They could have lessened the harm if they’d followed the conditions that the court placed on the City of Abbotsford,” Cowichan Community Care Network told The Discourse.

North Cowichan did not conduct any consultations with the community according to Cowichan Community Care Network.

The Discourse has reached out to the municipality for comment, but has not received a response as of publishing.

The City of Abbotsford was also ordered by Sukstorf to complete an individual needs assessment for each occupant to identify appropriate accommodations.

When asked if North Cowichan conducted a needs assessment, Horn said that falls on the individual service providers who directly work with the community.

Another concern the Cowichan Community Care Network has is the lack of clarity around what will happen to the belongings of residents.

The notice from North Cowichan states that anything left behind will be thrown away, but if belongings were labeled, the municipality would store them for up to 30 days to be claimed at a later date.

Legal observers from Cowichan Community Care Network say encampment residents were not clear on how to label their belongings and that some were mistakenly thrown out as a result.

Ultimately, the Network said anything short of housing people is not enough.

“Moving people from one outdoor location to another, disrupting an already unregulated drug supply, separating people from their community and the services they need, is nothing more than an act of control, and pandering to the most hateful factions of this community,” the group said.