This story contains descriptions of suicidal thoughts. Please read with care.

In July, a healthcare worker reached out to The Discourse about the treatment of their client Bella Campbell, a 79-year-old member of Ahousaht First Nation and residential school survivor who had lived in a Nanaimo Affordable Housing Society-run building on Georgia Avenue since March.

“From day one she was being, I would say, bullied by the on-site management there,” the healthcare worker, who asked that their name not be published due to the nature of their work, said during the conversation. “They’re not coming to her in a good way to try and figure out what it is that’s happening. They’re just coming in and accusing and blaming and threatening. It’s so inappropriate.”

As described by the worker, the bullying included addressing Bella in disrespectful ways, accusations of connections to drug dealers she does not know and blaming her for making noise when she wasn’t even home.

These types of incidents are not isolated. At least 30 of the people interviewed by or who contacted The Discourse in the process of reporting this series — which included residents, former employees and members of the previous board — expressed similar concerns about the manner in which tenant relations were handled by Nanaimo’s largest non-profit housing provider.

Read more: It Takes a Village The Discourse investigates low-income seniors’ housing

For several months, The Discourse has been investigating allegations about NAHS, which range from intimidation and harassment to assault, being unfairly targeted for eviction and the unauthorized removal of funds from tenant accounts for services they never agreed to.

The healthcare worker’s story was familiar. A retired lawyer named Janis Magnuson who lived in the same Georgia Avenue building had contacted me separately a month prior, with the same concern, that an older tenant in her building — Bella — was being harassed by NAHS staff.

Bella declined to be contacted for an interview, but in early September I received a distraught call from her daughter Louise Campbell, 62, who said that Bella — along with Louise and her sister Colleen Campbell, 58, who also lived there, and are also residential school survivors — were being evicted from their unit at the end of the month.

Louise says her mother Bella got behind on her portion of the rent — approximately one-third — for about three months while the family was in and out of town dealing with a number of family tragedies.

In March, Bella’s daughter Angeline Campbell died. Two months later she lost her son Ronald Thomas, and then in July her brother Josepheus Campbell also died.

“My brother [Ronald] passed away in May. May 25 we lost him. And we had a funeral in Port Alberni around the beginning of June. And we come back home — we weren’t here all the month of May because he was in the hospital in Port Alberni — and there was a notice on our door saying that we had noise complaints. We weren’t even here to be making noise,” says Louise.

“Each time mom was late for rent I took the time to explain our situation to the workers at the NAHS office,” she says, and adds that her main concern is that she doesn’t feel NAHS follows proper guidelines and procedures in that they never phoned or visited to discuss the complaints.

If a resident who usually pays rent on time calls ahead to arrange a late payment because of financial difficulties one month, the landlord and tenant may be able to work out an alternative date for payment, according to the Residential Tenancy Branch (RTB). “We encourage housing providers and residents to try to resolve disputes on their own,” BC Housing advises in a guide for housing providers like NAHS.

“This is all pretty much racial (feels like it to us) because we are targeted and never given a chance to prove or explain our parts about all the complaints against us,” Louise said, via email.

Immediately after her uncle’s death in July, Louise says they returned from dealing with family in Ahousaht and went straight to the office to pay Bella’s rent. “We let them know that we just got in the night before and what had happened and they were like, ‘Oh, my condolences, I’m so sorry’ and whatnot. But the next day, the same lady that I gave the rent to, she comes in with an eviction notice.”

“We do our best to accommodate our tenants, including if they have financial hardship and have challenges paying rent,” NAHS CEO Andrea Blakeman responded, via email, when asked about their policy for dealing with tenants who may have missed a few months’ rent due to emergency circumstances, such as the death of a family member.

“However, occasionally and in rare instances, we may have to evict a tenant due to non-payment of rent or other matters that have led to a material breach of a tenancy agreement. This is never our preferred option and always our last resort.”

The healthcare worker who originally contacted me about the Campbells’ situation says they’re concerned about the broader implications this kind of housing stress can have on tenants’ health.

“I work primarily with an older population, and medically complex, and compromised, and vulnerable. And the fact that they have all of this stress at home, which is supposed to be the place where they can feel relaxed and safe, it just jeopardizes their health that much more. I think it’s egregious and I want it to stop,” they say. “I just feel that the management and the way that the buildings are run is not as they’re advertised. NAHS is supposed to be this inclusive, affordable … organization and I think they’re really falling short.”

After the eviction at the end of September, Louise contacted me again.

“I have been in the hospital this week. I had a small brain stroke because of all my stress lately,” she wrote, via text. “It’s frustrating but I’m getting through it right now.”

Bella and Colleen have now secured housing with help from M’akola Housing Society, an Indigenous affordable housing provider, says Louise, but she is still struggling to find her own housing.

Read more: What are vulnerable tenants’ rights in non-profit housing?

‘It’s psychological abuse’

On the afternoon of Aug. 4, 75-year-old Buttertubs Drive resident Jim Power says he returned home to a message from his wife that the maintenance supervisor wanted to speak to him.

When he knocked on the door of his on-site office, the employee emerged with “a couple of four-by-four inch pieces of metal in his hands” and started swearing at him, Power recalls, adding he was also accused of removing a “no parking sign” and being “the leader of all the scum people in here.”

At one point he says the supervisor put his hand on his chest. Power stepped back, telling him not to touch him and that he had a medical problem in that area of his body.

“He said, ‘Get the ‘eff off my property, you’re going to be the first on the top of my list to be evicted from this place,’” Power recalls.

After he got home, Power documented the incident and made a report to the RCMP. He then contacted the Nanaimo Family Life Association, the Seniors First BC abuse info line, the Office of the Seniors Advocate and other organizations.

On Oct. 14, he says he received a written apology from NAHS CEO Andrea Blakeman, and was told the employee would be moved from that location, but still sees the supervisor around regularly.

At this point, Power says he would prefer to address the issue via an in-person discussion with NAHS staff and a board representative but is also exploring his legal options. He says he is also actively looking for a new residence for himself and his wife.

“This is blatant senior abuse, whether I’m a tenant here or not. For me it’s psychological abuse,” he says. “I can’t get over it. I think about it every day, still.”

This isn’t Power’s only issue with NAHS. When he moved into the complex five years ago, he set up a landline phone that cost him about $20 a month.

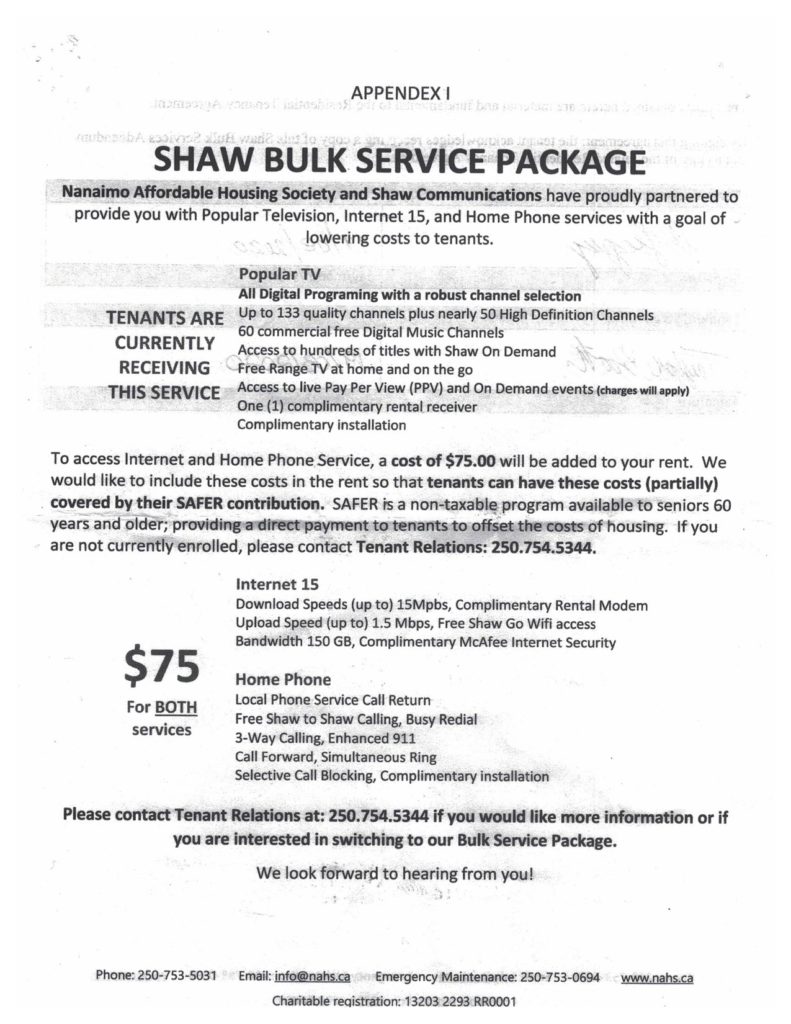

In the summer of 2020, NAHS sent out a notice to tenants about the upcoming implementation of a new bulk phone, cable and internet package with Shaw Communications that would cost residents an extra $75 per month and constitute part of a “new monthly rental rate.”

The package, where provided, was “mandatory,” the notice stated, and “could not be refused, substituted or eliminated by tenants.”

“We would like to include these costs in the rent so that tenants can have these costs (partially) covered by their SAFER contribution,” another part of the notice states, referring to a rental subsidy available to people 60 and older.

It’s unclear whether it was a better deal for residents like Power, who already had three-tier cable included as part of his rent, though it might have been cheaper for some.

“I told [NAHS’s tenant relations manager] I didn’t want the internet because I don’t have access to a computer. And I don’t need your cable, because cable’s in with my rent, and I got a phone from Shaw. So I don’t really need any of it,” he says.

“And that’s when we started noticing about six months later, they were taking money out without being authorized. Which is a type of fraud, in a way,” Power says, explaining he believes NAHS added the Shaw charge to his rent and then removed it from his bank account without his consent.

At this point, which he estimates was in August 2021, Power says he discontinued his pre-authorized direct deposit with NAHS, deducted the money they had taken from his account without his permission, and gave them the remaining balance the next time his rent was due.

As a person with disabilities, he was also battling serious health issues.

“I was waiting for my third heart defibrillator implant. And I was waiting for a call from my surgeon in Victoria at Royal Jubilee Hospital. And before he can get a chance to phone me, Nanaimo Affordable Housing Society cut my phone off,” says Power, who also previously worked as the complex’s live-in caretaker for 14 years, under different management.

“[NAHS CEO] Andrea Blakeman, she came within a couple of days after I complained about it. She said, ‘Well, you did have a cell, right?’ I said, ‘That’s beside the point, but I do have a cell. But you should never cut a phone off, even if you think the phone line belongs to Nanaimo Affordable Housing or not. That’s not a good thing to do in an emergency, like this situation.’”

Since then, Power says he reconnected his phone directly with Shaw and pays his monthly rent via cheque.

At least five other tenants in NAHS buildings also state they were pushed to accept the Shaw package whether they wanted it or not, and claim they had money taken from their accounts by NAHS without authorization.

“Some people don’t even have computers, and they were making them take that. Like basically, ‘You have to do this,’” says Anne Turner, 73, who reached out to The Discourse from where she lives in a NAHS-run building at Selby Street. “I don’t have to do anything I don’t want to do. And then when, of course, they took it out of my bank account, I was just like, ‘I never gave you permission to do this.’”

Turner has a master’s degree from Athabasca University and already had an internet contract with Shaw that suited her needs as a researcher.

“They just issued it like it was a rent increase, but it wasn’t a rent increase. And I was furious,” she says.

The provincial government implemented a rent freeze due to COVID-19 from March 18, 2020 to Dec. 31, 2021, though certain subsidized units were excluded. Even if rent increases had been permitted at this time, an extra $75 represents far more than the percentage of increase allowed in one year.

NAHS did not respond to The Discourse’s questions related to these rental increases but claim the Shaw package was not implemented without each tenant agreeing to it, according to RTB documents obtained by The Discourse.

Read more: What are vulnerable tenants’ rights in non-profit housing?

‘Part of a gang’

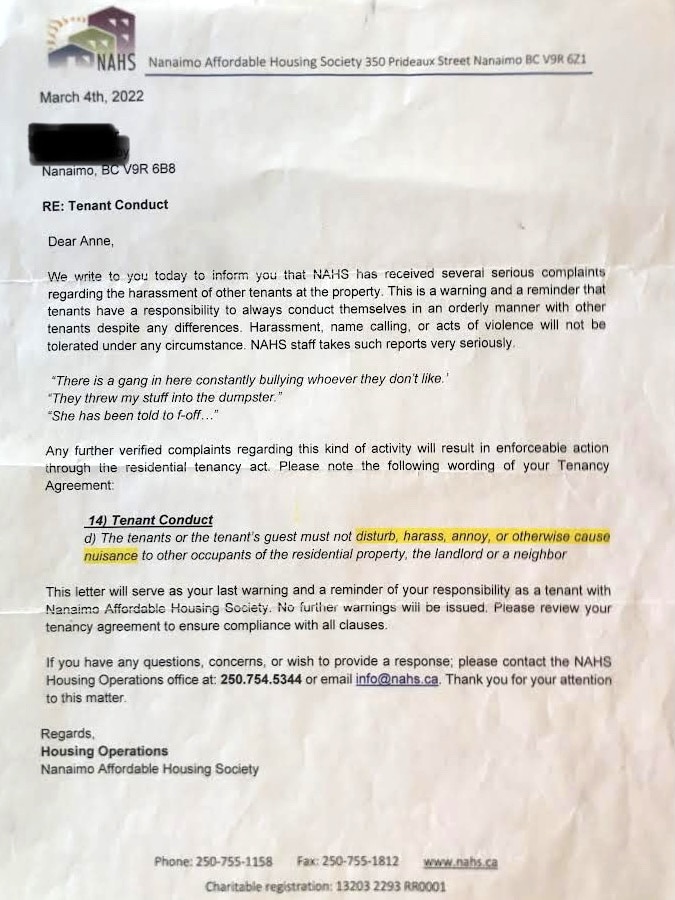

Aside from the issues with her internet, Turner says she received a letter on March 4 from NAHS staff detailing what they described as “several serious complaints” about her that ranged from bullying others as part of a “gang” to swearing at other tenants.

The letter informed her that this would be her “last warning.” though Turner says she had no idea what they were referring to and was unaware of any other warnings.

Confused, Turner shared the letter with some of her academic colleagues and connected with local advocacy representatives as well as the Office of the Seniors Advocate, which is appointed by the B.C. government to independently monitor seniors’ services in their interest.

During a phone conversation, the senior’s advocate agreed that it was harassment, Turner recounts, speculating that perhaps due to her status as a tenant “grandfathered in” from before NAHS took over, there was motivation to replace her with a new tenant who would pay higher rent.

NAHS declined to comment on these allegations. Turner was also advised by the advocate to send NAHS a letter to refute the claims.

In her written response to NAHS in May, Turner said the accusations “baffle(d) me beyond words” and caused her stress and anxiety. “I feel the nature of the letter was meant to threaten or scare me into complacency, with these incidents that you have accused me of,” her response states.

On Oct. 30, Turner emailed The Discourse to say she spoke to the NAHS employee who wrote the warning, who told her that similar ones had been sent out to others in her building and that since the letters had been sent out, those actions had stopped.

“I told [the employee] that I was innocent of all of the accusations and I was really concerned as to when I was going to get the written apology that I asked for. [The employee] was rather lost for words but finally she did apologize to me,” Turner wrote.

The Discourse requested an interview with NAHS CEO Blakeman via email, and included a detailed list of allegations levelled at the society. After consulting with NAHS’ board of directors, Blakeman responded with an emailed statement.

“Our tenancies are guided by the Residential Tenancy Act and we follow the policies and procedures as outlined in the Act. There are times that our tenants have concerns and we do our very best to address these in a timely manner,” the statement said, in part.

Like many non-profit housing providers, NAHS staff “often deal with very challenging issues, such as hoarding, fire and electrical overload, and disputes between tenants” and NAHS does its “very best to address these.”

Should tenants have complaints, they “can connect with the RTB if they feel they are being treated unfairly by NAHS,” Blakeman added.

‘I cannot conclude that the tenant actually had rent amounts owing,’ rules the RTB

Last Christmas, Global News filmed a feel-good segment on Nickie Wilson, 66, when her quick thinking likely saved her neighbour Bob Climt’s life.

But there was something Wilson didn’t tell anyone — that she had almost refused to go on camera because she was in the midst of fighting eviction from her Buttertubs Drive residence and was afraid it might draw negative attention.

Though in previous years Wilson says she always paid her rent on time and in full, when COVID-19 hit, she ran into some trouble.

It started in 2020, when she missed appointments with the tax volunteers who helped the older residents at her complex and didn’t file her taxes for two years. Because of the missing tax information, when she turned 65, her disability payments didn’t transfer into pension payments, and she was without any income.

“I’m waiting for my Old Age Security for one, two, three months and so I phoned up and they said, ‘We didn’t get [your taxes],’” she says. “I was trying to do it online, with Ottawa and income tax in Victoria and everything, but it just didn’t go through… I just had the run-around.”

In the midst of the confusion, Wilson’s 87-year-old mother — who was already battling cancer — died from COVID-19 in Victoria. At the same time, Wilson was shuttling between the hospital, her home in Nanaimo, and medical appointments in Vancouver, where she was receiving treatment for eye-related health problems that ranged from detached retinas to macular degeneration.

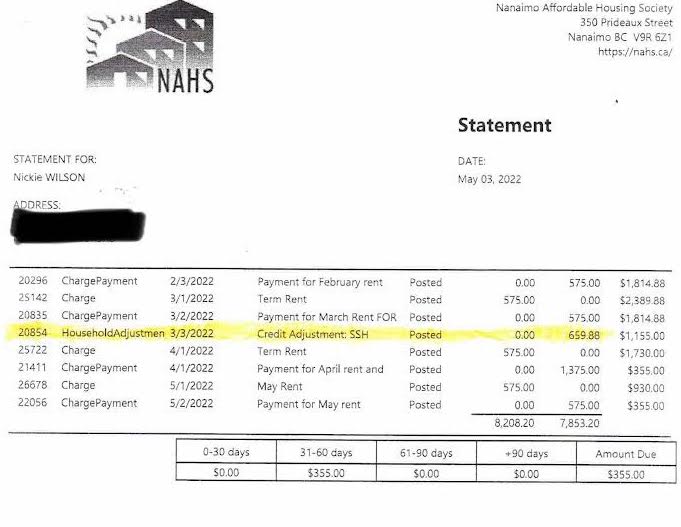

In financial statements and records provided by Wilson to The Discourse, she appears to have missed three consecutive $500 rent payments from June to August 2021.

Over the months that followed, NAHS served Wilson with a number of eviction notices into the summer of 2022. During this time, Wilson appealed to NAHS to explain her financial situation, according to letters and emails shown to The Discourse, but struggled to get a clear picture of what exactly was owed.

“I said, please just give me a price. What I owe, and how much I’m paying now,” says Wilson. “I could have borrowed the money from anybody, I just wanted the right amounts.”

Despite her uncertainty, NAHS’s own financial statements show that Wilson did actually make a series of payments to them in addition to her ongoing rent — for example $465 in October 2021, $1,125 in December 2021, and $800 in April 2022.

Wilson wasn’t the only one confused. By December 2021 the case ended up in the hands of the Residential Tenancy Branch (RTB), where arbitrators also seemed bewildered.

In the RTB decision obtained by The Discourse, the arbitrator notes that in NAHS’s application, they spelled Wilson’s name wrong and wrote her monthly rent down as three different amounts ($500, $648.34, and $575).

The matter was moved to a hearing, and in the decision that followed, the RTB concluded that “the landlord has failed to establish that any rent was owed” and they were unable to determine if the amounts NAHS claimed were for rent, support services or the cable package.

Wilson’s tenancy agreement clearly states that her rent is $500 per month, and that her Seniors’ Supportive Housing (SSH) program services and cable were included within that rental amount.

However, for nine months, NAHS charged her an extra $73.32 per month for the SSH services, according to their financial statements submitted to the RTB.

They also charged her $75 a month for a cable package they described as mandatory, which, like other tenants, Wilson argues she never agreed to or wanted.

“It is unclear why the tenant would have been paying an additional charge for those services,” wrote the arbitrator in the Feb. 3, 2022 decision. “If the tenant should not have been paying those additional charges from the beginning of the tenancy when the tenancy agreement specifically included them in the rent amount, there may be no outstanding rent at all.”

As a result, they then cancelled the 10-day notice to end tenancy for unpaid rent that NAHS had applied for (also known as an eviction notice).

Under instruction from the RTB to work out the details of what she owed — if anything — Wilson says NAHS did then attempt to meet with her, but her advocate Roxy Noble had sustained an injury that left her unable to walk, and she did not want to meet with them without an advocate.

“I was sick. I was going through a mental thing,” says Wilson. “I said, ‘You know I got bad eyesight. You know my advocate took a fall. And my computer’s down, I have to pay to get that fixed to get all my information, my documentation. Give me time.’ And they kept harassing me, for two weeks in a row. So I just hung up on them.”

Within a month, NAHS threatened Wilson with eviction again.

This time around, their paperwork was just as confusing. Inexplicably, NAHS issued two eviction notices to her on the same day — Feb. 25, 2022 — each claiming she owed a different amount: one $1,364.88 and the other $1,155.

Uncertain, Wilson didn’t respond. By law, if a tenant does not dispute an eviction notice or pay the outstanding rent within five days, they can be forced to move out. However, given that the RTB had just essentially ruled that she may not even owe anything, Wilson says at this point she was confused.

NAHS then returned to the RTB to say they had received no response and asked for an order of possession. This time it was granted — which meant Wilson had two days to gather up and submit all of her documentation and request that the case be reviewed, or she would lose her home.

In their response, Wilson and her advocate argued that they believed the order of possession had been obtained by fraud, and pointed to the extra charges for SSH services and the unauthorized removal of funds for the cable package from her and other tenants’ bank accounts, as well as the RTB’s own prior decision saying she may not even owe NAHS anything.

They sent it all off, and were told the order of possession would be paused until the adjudicator reviewed the case and made a decision. By now it was mid-April, but they didn’t have to wait long.

Within days, the RTB arbitrator informed Wilson that they had “submitted sufficient evidence to prove to my satisfaction that the [previous] decision may have been obtained by fraud.”

In addition, the discrepancies over what Wilson owed in rent carried forward. A new hearing was scheduled for Aug. 19, 2022.

However, before the hearing could take place, NAHS went after Wilson again. On May 3, she received a letter stating that she owed $355 in unpaid internet bills and that if she didn’t pay the balance in six days, her internet would be cut off.

This time, Wilson and Noble noticed something curious. Buried in a financial statement attached to the letter, NAHS had quietly reimbursed the SSH fees they had mistakenly charged her for — $659.88 in total.

“Thank you for the reimbursement as you have overcharged me for months, demanding I pay inflated monies owed to you,” Wilson wrote back. “It would have been nice to receive an explanation or an apology for your errors.”

She then requested that they not cut off her internet before it could be sorted out at their upcoming RTB hearing in August, as she had been paying her cable package bill for months at the office in cash, which she did not receive receipts for.

NAHS responded by sending her another eviction notice on June 6.

At this point, Wilson felt defeated. Though she didn’t believe she owed them anything, she says she decided to just pay NAHS so they would leave her alone.

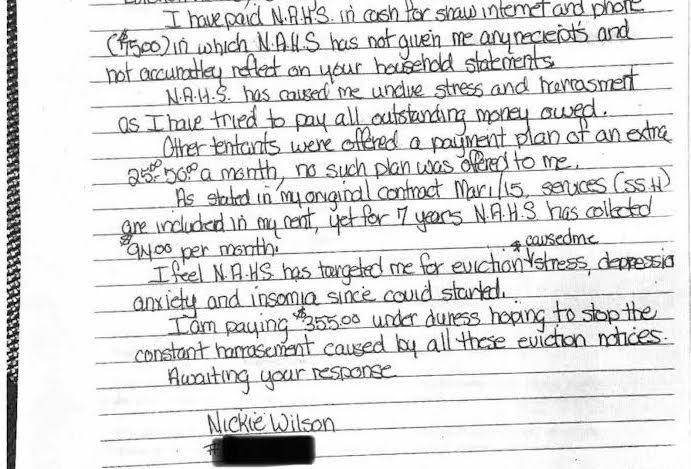

“I feel NAHS has targeted me for eviction and caused me stress, depression, anxiety and insomnia since COVID started. I am paying $355.00 under duress, hoping to stop the constant harassment caused by all these eviction notices,” she wrote in a response letter.

On Aug. 19, the RTB made its decision. Once again, it was unclear what exactly the tenant’s base rent was, nor could the landlord “provide a clear accounting of the correct amount owing in this hearing,” the arbitrator wrote.

The arbitrator noted the “conflicting messaging” of the two eviction notices sent to Wilson back in February, each stating she owed different amounts, and added that NAHS also “could not provide a sufficient explanation for this in the hearing.”

“From this hearing I cannot conclude that the tenant actually had rent amounts owing,” the arbitrator concluded, adding the landlord’s evidence as presented in the hearing “was insufficient” to prove it.

For these reasons, the RTB then ordered that this eviction notice also be cancelled and NAHS’s application for an order of possession and reimbursement of rent amounts be dismissed.

Pursuing justice

Though the ruling was something of a relief, one of the things that still bothers Wilson is that she was almost evicted over money she doesn’t believe she even owed.

“I paid up the money and then [the RTB] just dismissed the case,” she says. “If I would have known that, I would have pursued it more.”

Roxy Noble, Wilson’s advocate, says the question still remains as to whether NAHS’s order of possession was obtained by fraud, and what that means.

“We are still pursuing justice,” she says.

When it comes to the fraud question, theoretically, the RTB’s Compliance and Enforcement Unit could continue to investigate, and do have the power to make administrative penalties, says Robert Patterson, a lawyer at the non-profit Tenant Resource and Advisory Centre (TRAC), but he’s “never seen any examples or evidence of them doing that.”

Beyond getting a new hearing, “it doesn’t usually lead to any further consequences,” he says, though “it would be great if the RTB had the capacity and the resources to be able to intervene in cases like this.”

Read more: What are vulnerable tenants’ rights in non-profit housing?

There’s nothing in the Residential Tenancy Act that prevents a landlord from repeatedly issuing eviction notices, says Patterson, nor is there an automatic penalty or compensation if, like Wilson, the RTB repeatedly rules in a tenant’s favour.

“It’s frustrating for tenants, because the only way the tenant can try and stop a landlord is really just to ask for compensation for the harassment that results from the issuing of unsubstantiated notices. And the tenant can only get that in extremely egregious cases,” he says. “It’s also a pattern that you see from landlords quite frequently, honestly, where the landlord decides, ‘We want to evict this tenant, we’re just going to keep trying until it works.’”

Wilson’s case is remarkable, he notes, in that even though she missed the deadline to respond to the final eviction notice, she still managed to get a review of the case and then a new hearing.

“The grounds for review are so narrow and the bar so high — typically [tenants] just lose,” he says. “If a tenant misses their deadline, they are conclusively deemed to have accepted the end of the tenancy. Because really, our eviction provisions are written — in many ways — to prioritize efficiency of kicking people out, over people’s right to defend their right to stay in their homes.”

Part of TRAC’s advocacy around evictions has been to lobby for better policy and more flexibility around the default two-day minimum when granting an order of possession.

“There’s absolutely zero way that a tenant living in affordable housing can find somewhere to live in two days … the odds seem astronomically small. So if a landlord is going to push through that eviction, on the mandated deadline, they’re going to be on the street,” he says. “The point of tenancy law is to protect tenants. It’s to protect people from homelessness and from eviction. And it’s just irrational to me that this is part of the way business is done.”

There’s no reason, legal or otherwise, why RTB arbitrators can’t use discretion around when a tenancy should end — for example, in cases where a rental is paid up until the end of the month, Patterson adds.

Facing her own possibility of homelessness at 65 years old, not long after losing her mother, Wilson admits that in her darkest moments she had begun to make arrangements for her own death, going so far as to ask other tenants if they would help pack up her belongings after she was gone.

Ultimately, it was support from her friend and advocate Roxy Noble, neighbour David Ball and other friends that helped her pull through, she says.

“They started picking on her right off the bat because she was standing up for her rights, you know?” Ball says. “But they took so much off her. It almost made her commit suicide. They were just hounding her, saying she had to leave and all this, putting notices on her door. I always had her back, though. I told her if she ever needed me, I’d be there for her.”

When I contacted NAHS CEO Andrea Blakeman about Nickie’s case back in June, she stated via text that “out of respect and privacy for specific situations, I will not be able to make any comment whatsoever about Ms. Wilson.”