This story is Part 3 our ongoing investigative series It Takes a Village. Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to be the first to read the next story.

Not long before Christmas last year, Nanaimo resident Nickie Wilson made some cookies and dropped a batch off for her 83-year-old neighbour Bob Climt.

Tenants often looked out for one another and shared food in the low-income senior’s complex at Buttertubs Drive where Wilson lived, so it was nothing unusual. Just the previous day, she had left a meal on his doorstep, but it hadn’t been picked up.

The next day, she noticed the treats still sitting there and got worried. It had now been a few days since she had seen Climt.

“I put the Christmas cookies out, phoned and phoned, looked through the windows, knocked a couple times, then came back,” she says. “That night I was just sick to my stomach about it, because that’s going on four or five days, right? So then I phoned the police and said, ‘I don’t like to do this, but I know his habits and when his light’s on, and it hasn’t been on for days.’”

Wilson suffers from seasonal affective disorder (or SAD), and as a result, she often opens the curtains of her unit to let in light. It also means she sees a lot of the comings and goings of other residents.

Under previous management, when anyone noticed a resident missing, a staff member was informed and they would retrieve the unit’s keys and immediately check on the person, says Wilson. The residents also used a “buddy system” and had other informal measures for tenants and staff to look out for one another.

In the months leading up to Climt’s disappearance, Wilson says she sounded the alarm about several other residents and was told by tenant relations staff at Nanaimo Affordable Housing Society (NAHS) — the nonprofit housing provider that took over management of the Buttertubs Drive complex in 2014 — that they no longer did wellness checks like they did before, and she needed to phone the police.

When Cst. Butler arrived from the Nanaimo RCMP, he broke into the unit and found Climt lying on the bathroom floor. While the man was still alive, Butler later estimated in a police report that Climt had been lying there in medical distress for up to five days.

Other Buttertubs residents have similar stories.

“My new neighbour two doors down here is a little tiny old lady, and she was always out on her scooter. And all of a sudden I didn’t see her, and her blinds were closed, and her mailbox was full,” says Catherine Robinson, 65, who has lived in the patio-style buildings at the Buttertubs complex since 2011.

“So I called tenant relations. I said, ‘Hey, something’s wrong with her, I feel it in my bones. Something’s just not right.’ And [the employee] said, ‘Well, call the police.’”

As Robinson went to the phone, she glanced out the window and noticed a truck pulling up to the unit, driven by a man she believes was one of her neighbour’s family members.

Robinson ran out the door and was told the woman had fallen, broken her hip, and had lain on her floor for a day and a half until she was discovered.

“How disgusting is that?” she says, adding the incident happened about six weeks ago and her neighbour appears to be recovering.

As the neighbour was a new tenant, Robinson didn’t have her phone number. But she remembers that the General George R Pearkes Senior Citizens’ Housing Society, which ran the complex before NAHS took over, used to give out a phone list with tenants’ numbers and produced a monthly newsletter where new tenants were introduced to everyone. After NAHS took over the complexes in 2014, they stopped making them.

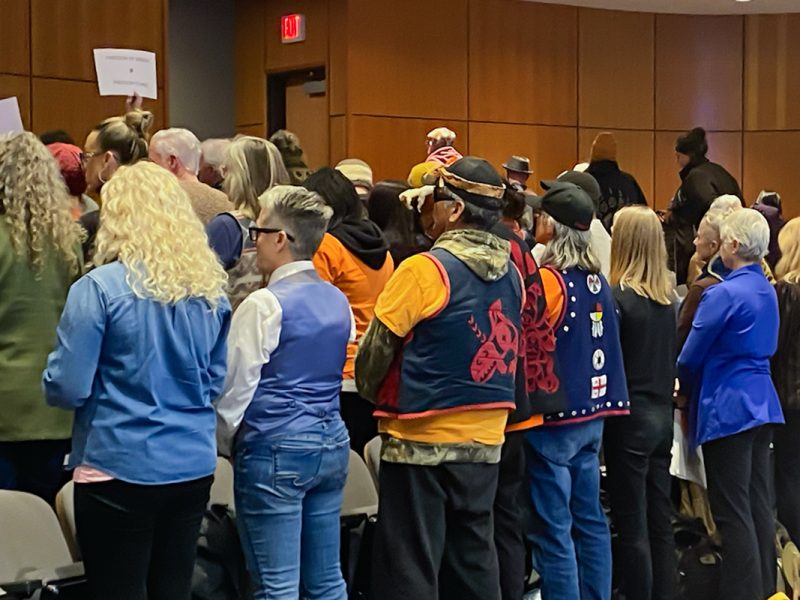

Related: Nanaimo seniors protest the loss of their ‘community’

Other vulnerable residents left alone

Buttertubs Drive isn’t the only NAHS-owned complex that has had problems with vulnerable residents left in their units — sometimes in medical distress — for days without help. The nonprofit operates about 15 buildings serving 700 tenants, most of whom are seniors, in Central Vancouver Island.

One resident died in a NAHS-owned building on Comox Road last year and wasn’t discovered for 97 days, according to BC Coroner’s service documents released in response to a freedom of information request by The Discourse.

This Comox Road resident was likely the same man Nanaimo RCMP say was found deceased in his unit by the building manager.

On the morning of July 7, 2021, police were called to a unit on the fourth floor of Corlett Place, a 73-unit low-income apartment building for independent seniors at 619 Comox Rd. NAHS acquired this building, along with seven others, from the Mount Benson Senior Citizen’s Housing Society in 2018.

The manager was told by a tenant that the man had not been seen for over a month, says Nanaimo RCMP spokesperson Gary O’Brien. “[The manager] also discovered that the deceased had not paid his rent for three months. They made entry with a master key into his unit, found the deceased. He was in an advanced state of decomposition.”

“I was just so pissed about that. It’s just wrong,” says a former NAHS employee with knowledge of the death who asked not to be named. “Somebody put a note on their door. If they haven’t got it, go bang on the door. It shouldn’t have been more than a month, if someone hasn’t paid their rent. Why aren’t they following up?”

The next afternoon, another body in a NAHS-owned property was found.

This time it was at an apartment building on 153 Wallace Street, which offers support for tenants of all ages with psychiatric and permanent disabilities in partnership with Island Health. Just before 3 p.m. on July 8, Nanaimo RCMP were contacted regarding a death on the fourth floor of the building.

“Individual had missed a medical appointment for that day, was a cause for concern,” says O’Brien in a phone interview. “Staff knocked on the door, no answer, noted a strong odor. Strong, pungent odor. Staff made entry to the unit, observed the deceased in a decomposing state.”

Though a coroner attended, O’Brien says the RCMP report does not offer an estimate of how much time had passed before the tenant’s body was found, though its decomposing state suggested it had also lain there for some time.

Though the cause of the previous death on Comox Road is still under investigation, BC Coroner’s Service has completed a report into the Wallace Street death. The Discourse requested access to this report more than a month ago, but the provincial service has not yet released it.

However, according to a document released by the coroners service through The Discourse’s freedom of information request related to three NAHS-run buildings, a death recorded at 153 Wallace St. occured due to “effects of heat.”

Though the document does not state when the death occurred, nine days had transpired between the tenant’s death and the discovery of their body, lining up with the July 2021 death described by Nanaimo RCMP.

The Discourse spoke with a number of former employees and a former board member of NAHS, some of whom said that prior to these deaths, they had advocated for the organization to have some kind of policy around how to respond when a tenant has not been seen in some time or is reported missing, as well as better maintenance and safety protocols in general.

One ex-employee said they “forced” NAHS to adopt a basic policy around wellness checks — to call the RCMP — not long before the July 7, 2021 death.

“If you’re not sure about someone’s well-being and they’re not answering the door, phone the RCMP and have them do a wellness check,” became the organization’s basic policy, they said, which aligns with what BC Housing recommends housing providers have in place. “That was definitely put in place because … staff were finding bodies and being quite traumatized.”

Several former employees said beyond that, the organization simply has no formal policy and procedure manual whatsoever.

The former NAHS employee added, “Most corporations have policies. … [At NAHS] everybody just does whatever. If one person does it this way, another person does it that way,” they say. “They had no idea what to do with properties or how they got by. They were floating along. It was just stunning, the ignorance.”

When asked, NAHS CEO Andrea Blakeman said via text that the organization “follows BC Housing and or BCNPHA recommendations to the best of [its] ability on every site,” but did not respond to a question regarding whether they had an internal policy and procedure manual. NAHS is a member of the BC Non-Profit Housing Association and partners with BC Housing on projects.

“From a first responder perspective, I think it’s prudent that care facilities up their game, especially during the hot summer months,” says O’Brien. “To have not had any contact with somebody for 30 days seems extreme. But I would think it would make perfect sense to either have a weekly contact or every second or third-day contact. I recognize you know, that they’re all short-staffed, they’re all put to the limit. But when you’re dealing with fragile people, with all of them probably having underlying medical conditions, days and even hours can make a big difference.”

Cases like Bob Climt’s at the Buttertubs complex, where the tenant was found alive on his bathroom floor after five days, can easily end in a death that is “natural, but preventable,” O’Brien adds.

Wellness checks could save lives during exteme heat, says coroners service

Though the majority of NAHS’s housing units are for independent seniors, many tenants live with chronic health conditions, alone, in poverty and in older buildings that are prone to dangerously high temperatures. These residents are disproportionately at risk of becoming ill or dying during extreme heat events, according to a B.C. Coroners Service review of heat-related deaths from the 2021 heat dome.

Identifying vulnerable populations and supporting them during extreme heat events was one of three recommendations in the June 7 report.

The investigation found that, of the 619 people who died due to the week-long extreme heat event, 79 per cent of the deceased were over the age of 65, and more than half lived alone and were indoors at the time of death. In addition, most were materially or socially deprived and didn’t have access to cooling systems like air conditioners or fans.

Some priority actions identified by the death review panel were to “consider the adoption of community wellness checks.” Of the 619 heat-related deaths they reviewed, half were discovered as a result of a wellness check.

“Many [people who died of heat] communicated that they were feeling unwell and were having difficulty managing in the hot temperatures,” the report states.

Wellness checks meant ‘Neighbour would look out for neighbour’

When Nickie Wilson first became a resident of the 82-unit Buttertubs Drive complex in 2015, she recalls tenants were regularly checked on — either by on-site staff, volunteers or other residents.

Former staff and board members say this was a leftover practice from the General George R Pearkes Senior Citizens’ Housing Society (GGRP), a small community-based organization started by the Branch 10 Legion, which ran the complex from the early 1970s until it handed over ownership and assets of the Buttertubs Drive property to NAHS at the end of 2014.

The buildings employed an informal “buddy system,” says GGRP’s former vice president Roxy Noble, where residents in patio-style apartments facing one another would make sure to open their curtains once they got up in the morning to signal they were okay.

“So as soon as something like that didn’t happen, boom — radar — we need to go check,” she says. “Neighbour would look out for neighbour. And then if you didn’t see them, you let somebody know.”

GGRP management also deliberately cultivated a “community vibe” where everyone knew each other, which made it easier to keep an eye on tenants, says former board member and volunteer John Berlinghof, who was told he wasn’t needed anymore when NAHS took over the building’s operations in 2014.

Related: Why is this Nanaimo housing provider rolling back services for low-income seniors?

“They would come to us and say, ‘We didn’t see Bob today, he didn’t come out of his room and his curtains are still drawn.’ So we’d do an immediate welfare check. And we did, sadly, find some [deceased] tenants. But apparently because now there’s no situation in place for that to happen anymore, welfare checks don’t get done.” he says.

Robinson remembers these wellness checks clearly. In 2015, John’s wife, Sheila Berlinghof, worked as the complex’s manager, and would do the rounds every morning, Robinson says. Sheila was laid off later that year.

This practice goes back even further in the complex’s history. Resident and former live-in caretaker Jim Power says there was a safety system in place to check on residents when he worked at Buttertubs from 1984 to 1998, though he doesn’t recall any written policy around it.

Above every door was a red light connected to a control panel in the caretaker’s unit, he says. If someone was in distress, they could pull on a chain to make the light flash and notify him of their location.

“Sometimes it didn’t quite work 100 percent. And if it didn’t, we’d just go out on the street and see whose light was flashing,” Power says. “I think it was just a courtesy thing at the time that we did check in on people.”

Some Buttertubs residents are currently monitored by an emergency response system included within their support services program, but when asked if current NAHS staff still do regular checks on tenants, Power says no.

“No, they won’t — they would never help you,” he says. “There’s people that die in their units around here and people don’t even know they’re passed away for four or five, six days. You don’t see them and sort of knock on their door, blinds are not open. And eventually you either call the police or ambulance, and usually it’s the police that will come.”

Tenants who require assistance with daily needs are referred to local resources such as Nanaimo Family Life Association, which supports local seniors with housing-related needs, or home support, NAHS CEO Blakeman said in an email. “Should we or one of our residents have concerns about the well-being of a neighbour, we will attempt to connect with the tenant or their emergency contact and if no response we will call the RCMP.”

Power says in one case he asked staff at NAHS to check in on a Buttertubs resident for almost a year.

“But that’s not their policy. They say it’s independent living — you’re completely on your own,” he says, a statement that’s been reinforced by Blakeman in numerous interviews.

“[This tenant] had one of those families that just had one son and he didn’t really care too much, right? So my wife and I used to check on this lady all the time. And then I finally noticed she was going downhill, and fast. Sure enough, I phoned the police, and [they] phoned an ambulance. The lady had dementia. She went downhill within a matter of six weeks. Stuff like that happens, and that’s not the first time.”

What happened to the wellness checks?

Though previous protocols around wellness checks at some NAHS-run buildings appear to no longer be in use, the reasons why they were discontinued and exactly what effect their discontinuation has had are less clear.

Part of the problem may be staffing shortages, which NAHS CEO Andrea Blakeman has acknowledged are an issue.

“Getting staff for anything is like winning the lottery,” she says, and represents a “really, really challenging” part of running a large nonprofit.

However, staffing issues may not be entirely outside of the organization’s control. The Discourse was able to confirm that at least four former NAHS employees have either been terminated without cause or laid off within the last three years.

Former employees contacted by The Discourse expressed feeling overstretched and understaffed, while confused by the number of layoffs. One of these employees spoke of being regularly called out at various hours to service all 17 NAHS-run properties and worked to the point of exhaustion.

Holding fewer staff responsible for more tenants and buildings was considered part of a cost-saving strategy touted by both NAHS and BC Housing, according to documents obtained by The Discourse.

When NAHS took over management of the Buttertubs complex, they viewed employees working there as “underutilized services” and saw an opportunity to “leverage” them for use at their other buildings and projects, states a 2018 BC Housing report that used the Buttertubs complex as a case study.

This meant existing staff, initially employed by GGRP to only look after the tenants at Buttertubs, were tasked with working at multiple NAHS-owned buildings all over town.

Before the Buttertubs complex’s community hall was demolished by NAHS in 2019 to make way for a new housing complex, former activities director Lynda Gamble says there was an “open door” policy at the hall. Residents were told to come in as much as possible and use the space like an extra living room — in part for social connection, but also so staff could keep an eye on who was around and who was missing.

“We used to encourage them to come to the hall in the summer when it was so stinking hot. Not all of them have air conditioning, right?” she says. “It was a community.”

Anna Cooper, a staff lawyer with Pivot Legal Society, which advocates for the legal rights of low-income tenants and other people living in poverty, says it’s concerning to see instances of communal spaces and interaction between tenants eroded.

“Was there more safety when people had these communal spaces, which actually promoted people being connected and checking in on each other?” she asks. “And how has new building design or new management design undermined existing safety between tenants?”

Related: It Takes A Village

NAHS board member Bob Moss says while it’s true some of the smaller housing societies like GGRP or the Mount Benson Senior Citizen’s Housing Society — whose board he also served on — were “quite hands-on” in their operations, “regrettably, it’s hard to have a larger organization that has enough volunteer support to make those things happen. So as the organization grows, and based on the changing requirements at all levels of government, it’s not easy to provide the same level of hands-on services,” he says.

“It comes at you from all angles, right? Trying to build a growing and sustainable organization when you’re in the nonprofit sector, you have to be very focused on what services you can provide and which ones you can’t provide, within the limitations that you’ve got,” he says.

As a board, they understand that the need for affordable housing is steadily growing, he adds.

“We’re already in a position where there isn’t sufficient affordable housing in the mid-Island market,” and need is growing much faster than supply, Moss says. With this in mind, the organization has prioritized increasing the number of affordable units and building their portfolio.

Between the Mount Benson merger and new projects under construction, NAHS provides, or will provide, more than 800 units, which Moss says is “a good start,” though he is quick to add that the community still needs “many more times than that” to satisfy the housing need.

Overall, NAHS is faced with the same challenges as the private sector when it comes to the rising cost of supplies and labour, as well as financing, says Moss. And the balancing act between costs, revenue and residents’ needs is never an easy one.

“I don’t disagree that there’s a need for wellness checks, but is it the housing provider’s obligation to do that? Or are there other organizations in the community health side of things that might be able to do that? Andrea’s comments to you about independent living are certainly part of the model that we see going forward as being sustainable. And so that’s our primary focus, is to provide affordable housing for people who can live independently,” he says.

“It doesn’t mean we’re oblivious to the needs of the residents, at all. But there’s limits to what we can provide.” [end]

Next week, The Discourse dives deeper into who should be responsible for wellness checks on vulnerable tenants in the event of extreme heat or other emergencies. Subscribe to The Discourse Nanaimo’s weekly newsletter to be the first to read it, or visit It Takes a Village to catch up on this series.