A massive barge, carrying roughly 12.4 million litres of fuel, gas and diesel was disconnected from its tugboat southwest of Bella Bella, B.C. earlier this week raising fears of a spill. The Zidell Marine 277 barge was near “popular local fishing grounds,” according to the Heiltsuk Nation.

The threat of leaking fuel is a major concern for the community. In October 2016, the Nathan E. Stewart barge sunk, spilling more than 100,000 litres of diesel into marine habitat. While the Zidell Marine 277 barge has been safely anchored, the Heiltsuk Nation says the incident highlights a need for a local response centre to respond to and prevent spills.

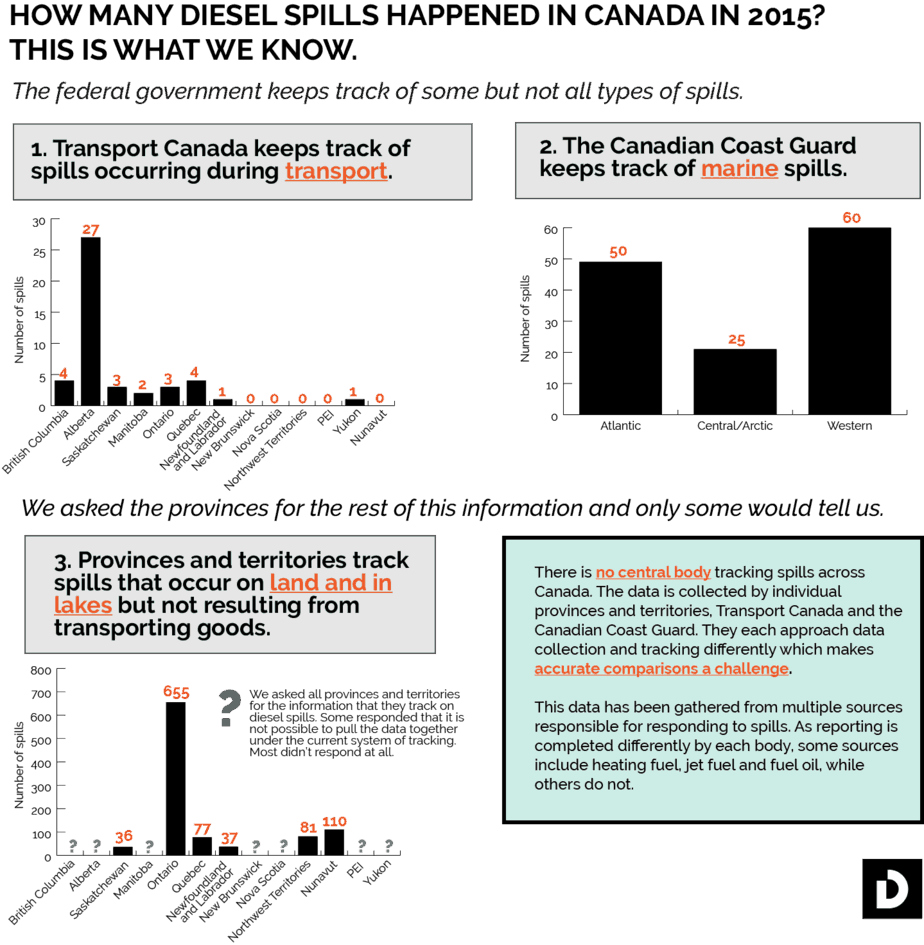

But how common are diesel spills in Canada? Since a reporting trip to Inukjuak, Quebec, a remote diesel dependent community, I’ve been trying to answer that question. The process of trying to access data on diesel spills has revealed a web of bureaucracy that ultimately means it’s hard to know the true cost of Canada’s diesel dependency.

Discovering the lack of national data

In October 2016, residents of Inukjuak, Quebec were still cleaning up a diesel spill that had happened 13 months earlier. It was a painstaking process that involved scooping up every bit of soil and rock that was contaminated and then loading it onto a tanker. Everything was then shipped thousands of kilometers south to be disposed of safely.

The remote town of over 1,300 people, on the east coast of Hudson Bay, is one of about 200 communities in Canada that rely on shipments of diesel to heat and light their communities. This spill occurred when workers made an error while transferring fuel from one storage tank to another, resulting in 13,500 litres of diesel leaking onto the ground.

The risk of such spills is one factor that’s spurring the community’s drive to embrace clean energy and displace diesel — because they rely on the land and local waters for much of their food supply. Two other communities in the region have had to deal with similar spills in recent years, including this particularly bad spill in nearby Ivujivik.

I was in Inukjuak to report on the community’s attempt to get off of diesel power. I left wondering, do these three spills reflect a larger problem? I decided to narrow in on one year of data, 2015, to try to get answers.

My first call was to federal Transport Canada; they track diesel spills that occur in transit. There were 45 reported diesel spills in transit in 2015 with virtually all incidents occurring during road transport or during handling at facilities.

Spills that happen on the ocean, but not during transportation, like illegal dumping, are tracked by the Canadian Coast Guard, which operates under the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). The Coast Guard has a database for collecting and reporting all marine pollution incidents called the “Marine Pollution Information Reporting System,” which includes diesel spills.

The majority of the information was not easily accessible and required some Freedom of Information (FOI) and Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) requests to gain better access and insight. I filed requests with Transport Canada and the DFO. After about a month, some information trickled in, but there was still no mention of the 2015 Inukjuak spill.

It turns out that it’s the job of the provinces and territories to track diesel spills that occur on land and in lakes, as long as they don’t happen in transit. I contacted all 10 provinces and three territories to request their own diesel spill data sets. Initially, only Saskatchewan (36 diesel spills), Newfoundland (35 diesel spills), and the Northwest Territories (55 diesel spills) responded with data. Manitoba never acknowledged my calls at all, while PEI, New Brunswick and Alberta stopped responding after initial contact. A communications officer from B.C.’s Ministry of Environment told me that my request could not be fulfilled because the province’s electronic records for diesel spills are “not compiled into a searchable database.”

After lengthy delays, in Quebec provided the 2015 spill records — a total of 50 diesel spills, including the one in Inukjuak. The records showed, in addition to the three Nunavik spills I already knew about, there were at least two additional spills in the far north that year. Ontario responded eventually, reporting over 650 spill incident records for 2015 alone.

For 2015, the five provinces that responded reported a total of about 830, ranging in size from 0.01 litres spilled in Newfoundland (location and date not specified), to 28,000 litres recorded in January in Longueuil, Quebec. The records we did manage to access from federal and provincial governments were all very different in format — with often vague location data and insufficient information to know where federal and provincial records overlapped.

Sifting through this data, I’m left with more questions than answers. Such as, why is there such an enormous spill incidence discrepancy between what Ontario and the rest of the provinces and territories reported to us? Are other provinces less diligent in their reporting? What I do know is that I clearly underestimated the complexity involved in producing a single, accurate statistic that summarizes all the diesel spills across the country.

As communities like Inukjuak deal with a warming climate — which disproportionately impacts the Arctic — they are working to offset diesel with cleaner energy. In the process, they weigh the cost of diesel compared to alternative energy. Right now, the cost of cleaning up diesel spills is not part of the equation. Without this data, the full extent of diesel spills cannot be quantified for the public and decision makers to see as they continue to grapple with how to power Canada’s remote communities. [end]

Data visualizations for this story were created by Caitlin Havlak. The piece was edited by Lindsay Sample with copy editing and fact-checking by Jonathan von Ofenheim.