As The Discourse’s sustainable development reporter, I send out a newsletter once every two weeks. Check it out and if you want to get content like this in your inbox, subscribe here.

If you’re a regular reader, you’ve probably noticed that we have a new look and feel. That’s because we’ve just launched the beta version of The Discourse. We’re building a new approach to journalism in Canada so we’ve got a new name, a new website and new ways for you to contribute to our work. Next week, my reporting on plastic pollution is going to be one of the first pieces published on The Discourse so I hope you’ll stay tuned.

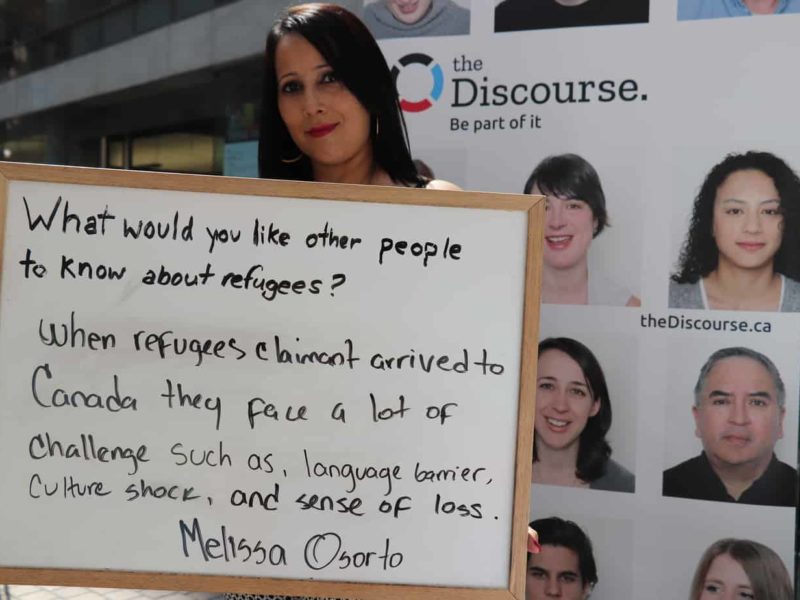

In addition to chipping away on my reporting on water pollution, I’ve been thinking about how Canada welcomes refugees. If you’re anything like many of my friends and family, you’re probably pretty proud of Canada’s refugee system. Especially how Canadians came together to support the government in its promise to resettle more than 25,000 Syrian refugees across the country.

But is Canada’s response to the global refugee crisis something we should be proud of? My colleague Francesca Fionda and I have started to look into it. And we’ve got a lot of questions. For example, even though Canada resettled over 46,000 refugees as permanent residents in 2016, more than 47,000 asylum seekers, who made a refugee claim when they reached the border in 2017, face an uncertain future.

Many asylum seekers face significant challenges when they arrive in Canada, including limited language skills, difficulty finding work and obtaining documents to prove what happened to them in their native country. Yet, they receive a sliver of the support granted to refugees who enter Canada through official channels. In fact, Liberal members of parliament have made trips to the U.S. over the last year to discourage people from Hispanic and Haitian communities from seeking asylum in Canada.

We’ve also come across some troubling data and stories about those who do get refugee status. According to research by the Canadian Council for Refugees, the loans refugees take from the Canadian government for the cost of transporting them to Canada can be so difficult for some to repay that they drop out of language classes or school to work. In addition, it typically takes 14 or more years for a refugee’s income to equal that of a similarly educated Canadian, according to research from the University of Manitoba.

As we continue to dig into this, we’re figuring out where to take this reporting and we’d love your feedback. Do you know people who came to Canada as refugees or asylum seekers that might like to share their experience? How well do you think Canada is doing? And what questions do you have? Message me on Facebook or Twitter, or email me to share your thoughts.

ICYMI

This week, I’d like to recommend two stories related to reconciliation and the child welfare system that moved, troubled and inspired me.

-

My colleague Brielle Morgan is covering the trial of a Siksika mother who is fighting to get her kids out of foster care. Indigenous kids are grossly overrepresented in the child welfare system: while they make up just under eight per cent of kids under 15 years old in Canada, they represent more than half of all children under 15 in foster homes. Even though one of this mother’s daughters tried to commit suicide in care and another drank bleach, the ministry is arguing the foster care system can care better for her daughters. This video will give you a quick snapshot of the issues Brielle’s reporting grapples with.

-

“Missing and Murdered: Finding Cleo,” is a podcast series by CBC’s Connie Walker that examines the contemporary impact of the Sixties Scoop, when thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their homes and placed in foster care or put up for adoption. The podcast traces the harrowing story of a group of brothers and sisters, who were scattered in homes across North America. They enlist Connie’s help to find out what happened to their missing sister Cleo, who died as a teenager after being adopted by a family in the United States. The podcast is so well-told, it’s hard to stop listening, all while offering a crash course in a dark episode of Canadian history. [end]