Undercover agents, search warrants and traceable forensic ink — all part of a multi-year investigation that ultimately busted an international crime ring moving millions of dollars of fraudulent goods into parts of New Mexico and California. So far, the investigation has put two men in prison and handed down thousands of dollars in fines.

The goods in question? Fake Indigenous art.

Selling fraudulent Indigenous art is illegal in the U.S. under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, and is punishable by up to five years in jail and a $250,000 fine for an individual — or up to $1 million for a company. Though jail time is rare, for the first time ever a man was sentenced to six months in prison and had to pay nearly $10,000 in fines in August 2018 for his part in a multimillion dollar scheme to import Navajo-themed turquoise jewellery made overseas — and sell it as authentic Navajo art.

A second man was sentenced a few months earlier to two days in jail and had to pay $500 for his lesser role in the operation.

“This landmark investigation has brought much needed attention to the rampant problem of counterfeit Native American jewelry and art in the marketplace,” said Edward Grace, the acting assistant director of one of the U.S. law enforcement teams that led the investigation, in an August 2018 press release.

“We hope today’s sentencings will deter others who would seek to defraud consumers and undermine Native American artists,” he added.

In Canada, no such law exists against misrepresenting inauthentic Indigenous-themed items as real — and tourist shops across the country are rife with fake Indigenous pieces.

In fact, a Discourse investigation recently found that 75 per cent of the tourist shops we visited in Vancouver that sell Indigenous-themed souvenirs appear to be selling some knock-offs, produced without any collaboration with Indigenous people.

“It’s sad” that Canada doesn’t have a law like in the U.S., says Liz Wallace, a Navajo artist and silversmith. She rallied Indigenous communities in New Mexico to testify in the trial leading up to the landmark fake art case there.

“People look at our material culture as up for grabs,” she says.

The U.S. law is one way to stop that, she says, though she’s quick to admit it’s not perfect. It doesn’t make cultural appropriation itself illegal, she points out; it only makes false advertising of Indigenous goods illegal. That means knock-offs can be sold as long as they aren’t advertised as authentic. For Wallace, that’s a big flaw. She also questions whether enough resources are going towards enforcement, and points out that the law only considers people Indigenous in the U.S. if they’re part of a government-recognized Indian tribe.

It’s “a bandaid over an amputation,” she says. But it’s still “better than nothing.”

We need a law, say artist and industry expert

Pam Baker would welcome a law that makes selling inauthentic Indigenous art illegal here in Canada.

Baker, a Squamish-Kwaguilth artist whose traditional name is Himikalas, runs Copperknot Jewelry from her home on the Capilano reserve in North Vancouver. She says she struggles to compete with products manufactured cheaply overseas then sold for less here to consumers who don’t necessarily care if they’re buying truly authentic goods.

“They would rather, let’s say, buy a pewter necklace made from a cast overseas that you’re going to buy for $12.99, compared to my cast necklace that we’re selling these for $20 retail — and we’re making no money off of it, of course.”

Indigenous tourism is a billion-dollar market with growing demand, according to B.C. Tourism’s latest strategic plan released in March 2019. But there’s a breakdown in the system that allows cultural appropriators to profit, says Keith Henry president and CEO of the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada. He says the onus must fall on the law to stop that.

“What we need is proper laws that ensure that we tackle these issues from a legal perspective,” he says. “I think there’s no other way around this.”

Right now tourist shops in Canada are filled with ambiguous labels that play on the “brand of Native,” Henry says.

But labels that say things like “Native Canadian” are “not actually Indigenous,” he says. They’re just “someone from Canada … and for some international markets, they would think that’s an Indigenous person.”

As a “truth-in-advertising law,” the U.S. Indian Arts and Crafts Act “prohibits misrepresentation in the marketing” of Indigenous products, making it illegal in the U.S. to “falsely suggest” something was created by an Indigenous person when it wasn’t. Knock-offs can still get by as legal as long as they have no labels that might make a buyer think they’re authentic. So products with labels like “Native-inspired” could be in compliance with the law.

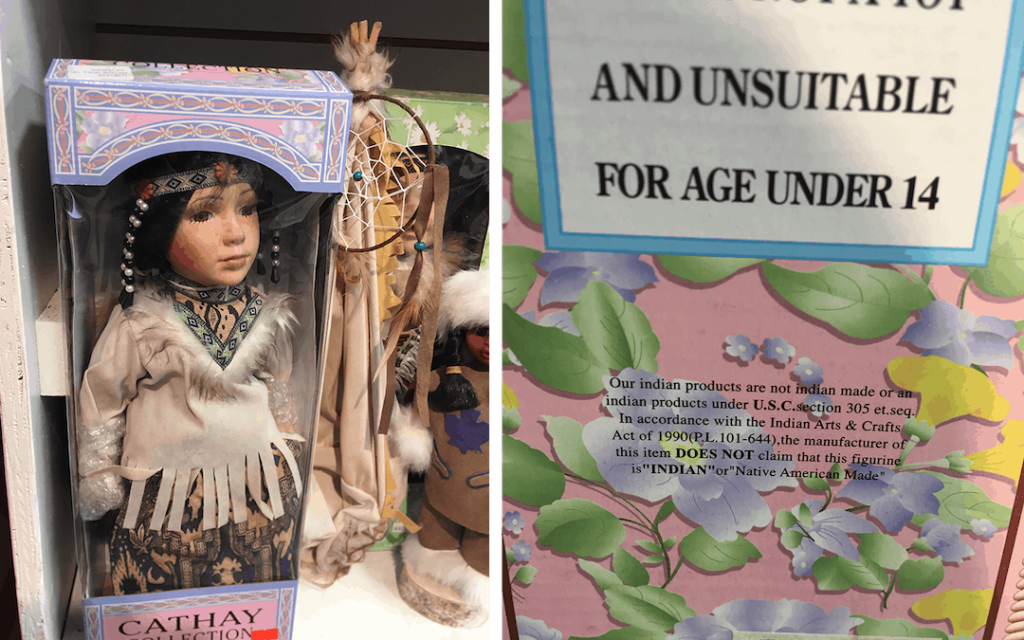

The manufacturer Cathay Collection produces a line of dolls, for example, that supposedly depicts an Indigenous figurine and includes a note for customers on the box: “Our Indian products are not Indian-made or an Indian product … In accordance with the Indian Arts & Crafts Act of 1990… the manufacturer of this item DOES NOT claim that this figurine is ‘INDIAN’ or ‘Native American Made.’”

‘Genuine Native Indian Craft’

During our five-month investigation, The Discourse visited 40 shops in Vancouver’s tourist hot-spots and catalogued more than 260 Indigenous-themed souvenirs like dreamcatchers, inukshuks and mini totem poles. Only 40 per cent of the products we traced had labels showing an Indigenous artist’s name or nation; the rest had tags with ambiguous descriptions of how the item relates to Indigenous culture — or no information at all.

A popular item we found in shops across the city was dreamcatchers. One distributor, KC Gifts from Cranbrook, B.C., includes labels on its dreamcatchers that read: “Indians hand crafted Dream Catchers enabling good dreams to slip through the web, while the bad dreams were caught by the web.”

While Tammy, one of the company’s owners, told us they have worked with some Indigenous artists on some products in the past and paid them royalties, she says their dreamcatchers are made in China. Indigenous people were likely not involved in their creation, she says — “not unless the manufacturer from China or wherever they are coming from is doing that.”

Royal Specialty Sales, based in Toronto, also sells dreamcatchers with a small label that describes “The Legend of the Dreamcatcher: A gift to Aboriginal people of North America, a spider weaved a special web in return for sparing its life,” it begins. A second label notes the items are handmade in China.

When asked about the labelling, manager Karen Davidson says, “Nowhere does it say that it is an actual authentic dreamcatcher and I am sure — I think it also says — that it is brought in from China. It’s certainly not made here.”

In several shops we found Indigenous-themed dolls made by a Quebec company called Koshuan, with labels that describe their products as: “Genuine Native Indian Craft.” The company didn’t return our numerous calls or emails requesting an interview, but admitted to Radio-Canada in 2017 that their dolls are not made by Indigenous people.

“I don’t want to start a petty war,” Koshuan owner Daniel Rivard reportedly told Radio-Canada’s Corde Sensible program in an off-camera interview in 2017. “We are in a free country, and people can manufacture whatever they want.”

According to this CBC report on the Radio-Canada investigation, Rivard suggested that his products could still be considered genuine Indigenous items even if they’re not made by Indigenous people.

‘They’re misrepresenting,’ says a U.S. special agent

Fake art is “basically destroying their Native American way of life,” says Phillip Land, special agent in charge of all the law enforcement operations for the southwest office of law enforcement for US Fish and Wildlife service, which investigates complaints under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

We described some of the items we found in our investigation here in Vancouver to Land, and while the law he works with doesn’t apply in Canada, he told us what he might do if he came across similar products in his jurisdiction.

For example, if he came across a doll depicting a supposedly Indigenous figurine in the U.S. with a label stating, “Genuine Native Indian craft,” he would certainly have some questions.

“With that, actually, they’re misrepresenting it, saying it’s ‘genuine Indian-made,’” he alleges. “The next step I want to look for is: is there initial by an artist that actually made that product, or was it mass-produced?” he asks. “I always like to know, who’s the artist?”

“We might’ve sent an undercover agent in there to ask more specific questions,” he continues, when asked what steps he might take to investigate if the company were American. “‘You’re saying this is Indian-made… and you’re sure it is? Can you give us any historical knowledge of artists who made this? What tribe were they associated with?’”

If the company fell within his jurisdiction in the U.S., the next step for Land would be to send them a notice letter to tell them about the law and what it prohibits. Right now, he has two full-time criminal investigators looking at complaints, as well as three to four people assisting from the Indian Arts and Crafts Board. Together, they respond to tips that come from the public and decide what should happen next. They even have a hotline 1-888-ART-FAKE.

Igloo Tag protects Inuit artists

Meanwhile in Canada, we have unofficially deputized Igloo tag detectives to investigate fake art, jokes Alysa Procida, the executive director of the Inuit Art Foundation.

Procida is referring to a network of people who are familiar with the trademark symbol featuring an igloo on a black backdrop called the Igloo Tag, which is attached to hand-made Inuit art and includes the artist’s name and where they come from.

The goal is “to protect Inuit works of art from fraud, cultural appropriation and theft,” explains Blandina Makkik, an igloo tag coordinator with the Inuit Art Foundation.

“When they go into an art gallery or a souvenir shop asking where the work came from or if they have a tag, I will get photos in my email,” Procida says.

For the Inuit people, art is synonymous with everyday life, says Makkik. “Art has always been in our culture, whether it be through song, through poetry, and even our implements, our clothing.”

Just over a quarter of all Inuit in Canada over age 14 are involved in the production of visual arts and crafts, and in 2015 the Inuit art economy generated $87.2 million a year for Canada’s GDP, according to a 2017 report prepared for Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.

As a registered trademark, the Igloo Tag provides the Inuit Art Foundation with a few legal avenues to pursue if the label is misused. While trademark infringement legal proceedings are “unpleasant,” Procida says, they’re “not the same as criminal legal proceedings.”

The laws in the U.S. have “a little bit more teeth behind them,” she says, something the Inuit foundation would welcome.

And while the Inuit have a foundation and a trademark to protect their art, “cultural appropriation is not a unique problem to the Inuit art market,” she notes.

Can copyright law help in Canada?

Cultural appropriation of Indigenous art has been going on for centuries, Kwakwaka’wakw artist Lou-ann Neel says.

Today it continues “in the form of copyright infringement on original Indigenous artworks,” she wrote in a proposal submitted in December 2018 to Parliament’s standing committee on Industry, Science and Technology, which is now reviewing Canada’s copyright law.

Neel pointed, for example, to “original designs being replicated for mass production without permission from the artist or compensation paid to the artist.”

She wants to ensure that Indigenous perspectives are considered as the committee reviews Canada’s copyright law, as it’s required to do by law every five years. “Our traditional art forms are owned by our people,” she explained to the standing committee in October 2018. “They are inherited rights that are passed down from one generation to the next. I come from an artist family. I am now the seventh generation in my family to continue practising our artistic traditions.”

But the Copyright Act as it stands right now does not acknowledge Indigenous forms of ownership, like “communally owned property, familial-owned property or properties held by the nation,” she pointed out.

Without any laws to protect them, “our artists continue to operate daily at under-poverty levels,” she told the committee. “We do not see the proceeds coming back to our communities. We don’t see royalties. Permissions have not been granted for the use of many of our designs in the first place.”

Neel would like to see a national Indigenous arts advocacy organization created that could build a network of support to help artists protect their work, apply for grants, manage their businesses, negotiate contracts and licensing agreements — and educate the public on Indigenous art and traditional knowledge, as well as copyright and intellectual property rights.

“People take our art because they don’t know any different,” she said. “And they don’t know any different because we’re not actively and proactively informing Canadian citizens about whether it’s appropriate to take designs.”

The standing committee is in the process of drafting its report and is expected to present its recommendations to the government in the coming months.

“Lots of really big, high-level things have been talked about and presented to that Parliamentary committee,” she told The Discourse. “Now, we await what their actions are going to be. We’re hopeful and still fingers crossed.”

For Neel, the most important thing is to support Indigenous artists, then figure out how legislation can play a role in protecting their work from appropriation and copyright infringement.

“I’m not sure that legislation as a first go is the best approach,” she says. There’s still lots of work to be done to rebuild what was destroyed by colonization.

“It has everything to do with restoring our culture, restoring our language, but also restoring economic viability and local economy,” she says. “It is our intellectual property, and we have a right to protect that.” [end]

This story is part of a series on fake Indigenous art in the tourism industry. It was edited by Robin Perelle.