Indigenous people living in B.C.’s Lower Mainland may have left their home nations for the city, but that doesn’t mean they left their culture behind.

Across the province, First Nations are steeped in languages, cultures and traditions that are interwoven with people’s identities. This culturalization stays with Indigenous people no matter where they move. It keeps them grounded and serves as a reservoir of strength during times of adversity.

So it was no surprise to me that our Urban Nation readers voted for culture as the theme they wanted Discourse reporters to tell stories about first.

But what is Indigenous culture and why does it matter? (And how is it that culture is so important to urban Indigenous people that they considered it more of a priority for reporters to cover than the Lower Mainland’s housing crisis and how it’s impacting Indigenous people here?)

Over the next several weeks, my colleagues and I at The Discourse will begin to document and unpack different layers of culture among urban Indigenous people in the Lower Mainland, starting with this framing piece.

[factbox]

Read our culture series:

Learning Cree and Ojibwe feels like ‘coming home,’ these urban Indigenous students say

Learning Cree and Ojibwe feels like ‘coming home,’ these urban Indigenous students say

If we lose our Indigenous culture and language, ‘we lose everything’

Elders help urban Indigenous youth connect to culture — if they can find each other

This residential school survivor is teaching a new generation to speak Ojibwe

Indigenous kids need better access to culture while in government care

Roots workers help Indigenous kids in care connect with culture. Why are there so few?

A Lower Mainland man’s search for what it means to be Métis

Fake art hurts Indigenous artists as appropriators profit

3 tips to make sure you’re buying authentic Indigenous art

How saying ‘I’m gay’ in Heiltsuk connects this Indigenous man to his ancestors

Speaking Tsimshian in the city

Learning my language is an act of defiance

These language classes are helping Indigenous people reclaim their ‘stolen heritage’

Concrete hoop dreams: East Van team comes second in B.C.’s All Native Basketball Tournament

[/factbox]

What do we mean by Indigenous culture?

Jerome Turner might live and work in Vancouver now, but the 41-year-old lives and breathes the Gitxsan culture he was raised with — the values, language, traditions, ceremonies and connection to land that he learned from his grandparents, growing up in the northern B.C. village of Gitanmaax. These ways of knowing and being are culture.

“Everything I do is Gitxsan,” Jerome says. “It doesn’t matter — like when I’m working in the film industry, I’m doing it as a Gitxsan person and within those Gitxsan values. I try to take that to everything that I do, every interaction.”

Why is culture so important?

Simply put, culture is at the core of Indigenous identity. It’s what separates us from other Indigenous nations, and it’s from nowhere else in the world but here.

As an Indigenous person, I echo Jerome. Culture is part of what my people, the Nuu-chah-nulth, call Ha-hupa, or teachings. A person who was ha-hup-chu (taught) walks through life with Issak (respect) for themselves, for others and for all things. Jerome and I come from different First Nations, and his culture differs from mine in some respects. Regardless, I get the sense by how he carries himself, how he speaks, that he has respect and that he was taught.

I’ve seen dreamcatchers, welcome poles and sweat lodge skeletons in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, untouched, because even in the blight of the crushing addictions and poverty of that neighbourhood, Indigenous people still respect culture.

And government and church at one time considered culture so integral to Indigenous identity that they tried to erase it out of Indigenous children in residential schools. I’m convinced that’s why Indigenous people embrace our culture so tightly today.

What about Métis culture?

Chris Trottier found out he was Métis at age 30 from his father, who he’d been estranged from since age three. The revelation inspired his journey to find out who he is, where he comes from and how he can practice the culture of his his people. Trottier is among the more than 23,000 people in Greater Vancouver who identified in the 2016 census as Métis (who the Supreme Court finally recognized as “Indians” under the constitution in 2016).

Trottier knows about the Métis sash and Louis Riel, but beyond that he’s still learning the layers of Métis culture. I have to admit that the Metis people’s culture is a mystery to me. I know of them, but I don’t know about them. Recently though, I’ve interviewed several Métis people, and they told me about feeling “othered” within the Indigenous community. I don’t want to perpetuate this. So, this is as much my journey of discovery as it is Trottier’s. I’ll add a link here to my story on Métis culture as soon as it’s done to share what I’ve learned.

What are the consequences of not knowing our culture?

Tsimshian citizen and Richmond resident Denise Halfyard grew up in northern B.C. in a devout Christian home. Her parents eschewed their culture because of her grandmother’s siblings’ experiences in residential school, where they were punished for speaking their language and practicing their culture.

“I grew up not knowing any of my culture,” she says. “My grandmother didn’t teach my mom, and my mom didn’t teach me.”

Denise began her cultural journey at age 40, when she attended an Aboriginal Day celebration, and it awakened her sense of identity and belonging.

Looking back, she realizes what she missed out on growing up. “I was just a kid and I didn’t understand,” she says. “How do you miss something when you don’t know it’s there?”

In Indigenous communities, elders, or older, knowledgeable people, have long passed down culture to youth, through their lived experiences and storytelling. But as more families move to urban centres far from home, a new cultural disconnect has formed between elders and Indigenous youth.

For one 16-year-old high school student living in East Van, this disconnection from elders is a loss that needs attention.

“We learn everything from our elders, elders are so sacred,” Bethany Sunday Shortt says. “We aren’t learning that knowledge that is supposed to be passed down.”

Where can we find pockets of Indigenous cultures preserved in the Lower Mainland?

Here in this city, which is often far away from people’s home nations, there’s still motes of light, the last embers of a still-burning fire — little flickers of cultural flame struggling to stay alight.

It’s in the language and cultural nights hosted across the city by different First Nations groups. It’s the regular gatherings of people from different nations at the Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre for weekly West Coast nights, monthly Métis nights, and pow wows.

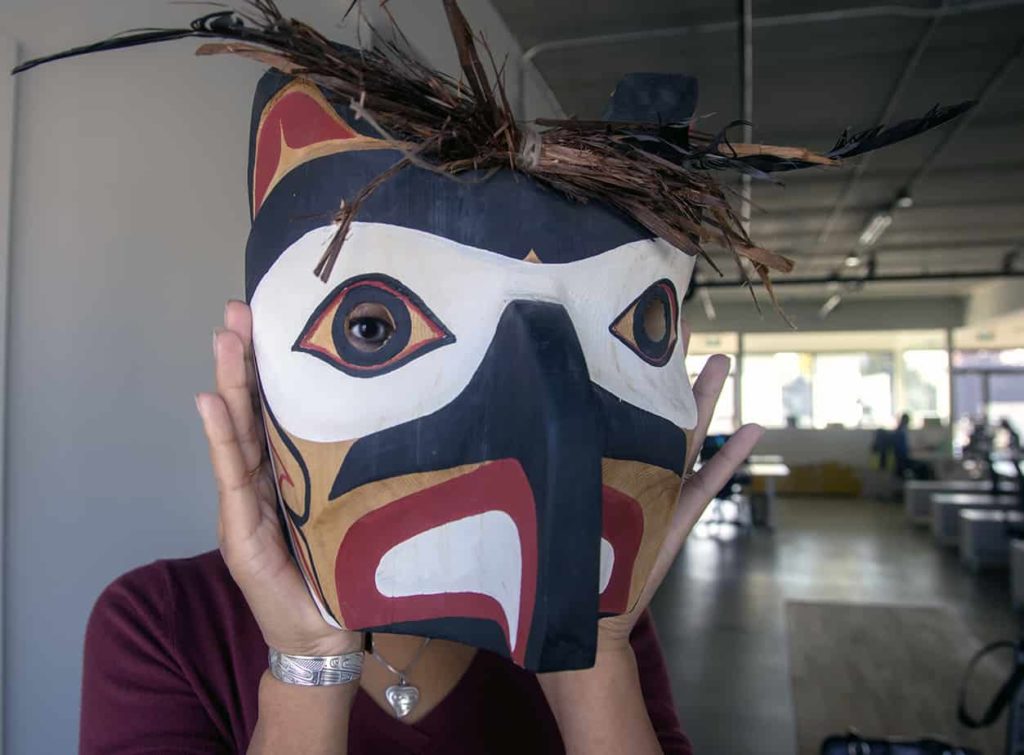

It’s when Indigenous artists produce wood carvings, paintings or jewelry at home or in studios. It’s the Gitxsan boy learning his people’s language out of his own curiosity, and the person in their 20s using a software app to learn words in their language then calling their grandmother to check them.

It’s parolees using a sweat lodge at their halfway house as part of their healing. It’s the single mother from a B.C First Nation who never grew up with her culture, but who uses other nations’ traditions as a surrogate culture here in the city. And it’s me using flashcards during my lunch hour to practice my Indigenous language while remembering my late mother speaking it.[end]

This story is part of our ongoing coverage of the urban Indigenous community in the Lower Mainland. Sign up here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter.