On a cold, damp Thursday night in Vancouver, Fifth Avenue near Scotia Street is dark and empty as businesses are closed. Near the corner, though, light flickers through the windows of the Native Education College.

Inside the college’s Indigenous longhouse-style wooden building, flames from an enclosed fire pit warm the interior, illuminating black and white pictures of elders on the walls. The gathering area is empty, but down the fluorescent-lit hallway, voices emanate from two classrooms.

Inside the classrooms, approximately 50 Indigenous men and women are reciting words: Plains Cree in one class and Ojibwe in the other. In the Ojibwe class, the words are days of the week, and will comprise part of a test the following week, instructor Monica Benson says.

The 2016 Census notes that, among Indigenous languages in Greater Vancouver, Cree is the most common mother tongue listed. But because it doesn’t originate from here — the traditional homelands of both the Cree and Ojibwe lie east of the Rockies — there’s no obvious place to naturally nurture Cree and Ojibwe languages. So organizations like the Pacific Association of First Nations Women are trying to fill that gap by creating surrogate spaces for local Cree and Ojibwe people to keep them connected to their identities.

“It’s important to offer Cree and Ojibwe to our local people because they live so far from their nations,” says Diana Day, head matriarch of the First Nations Women association, which organizes the courses. “We need to support them with language opportunities because our language is part of your identity. It’s part of who you are and where you come from.”

Language program launched

Last year, the association ran Indigenous Women Rise, a cultural program for local Indigenous women.

The organization connected with more than 500 women through the program, and Day noticed many were Cree and Ojibwe. Offering a language program seemed a natural next step, but she was hesitant. “I didn’t feel right because we’re not Coast Salish and this is their territory,” Day says. “But when I thought about the Cree and Ojibwe people that live here I wanted to make sure it was offered.”

The two eight-week classes are underwritten with a grant from the First Peoples’ Cultural Council. The classes are open to everyone, and Day hoped families in particular would attend. “That’s how we gather as a people. I want to see children come out and practice with their parents so they can go home and talk their language together.”

Instructors were hired in September and calls for applications to attend the classes were sent out. There was no shortage of interest. There were 175 applications for the classes’ 50 seats, Day says.

“As Indigenous people we live all over so it’s important for us to connect with our language,” she says. “Language connects you to ceremonies, foods and to our ancestors.”

Learning to speak Cree and Ojibwe

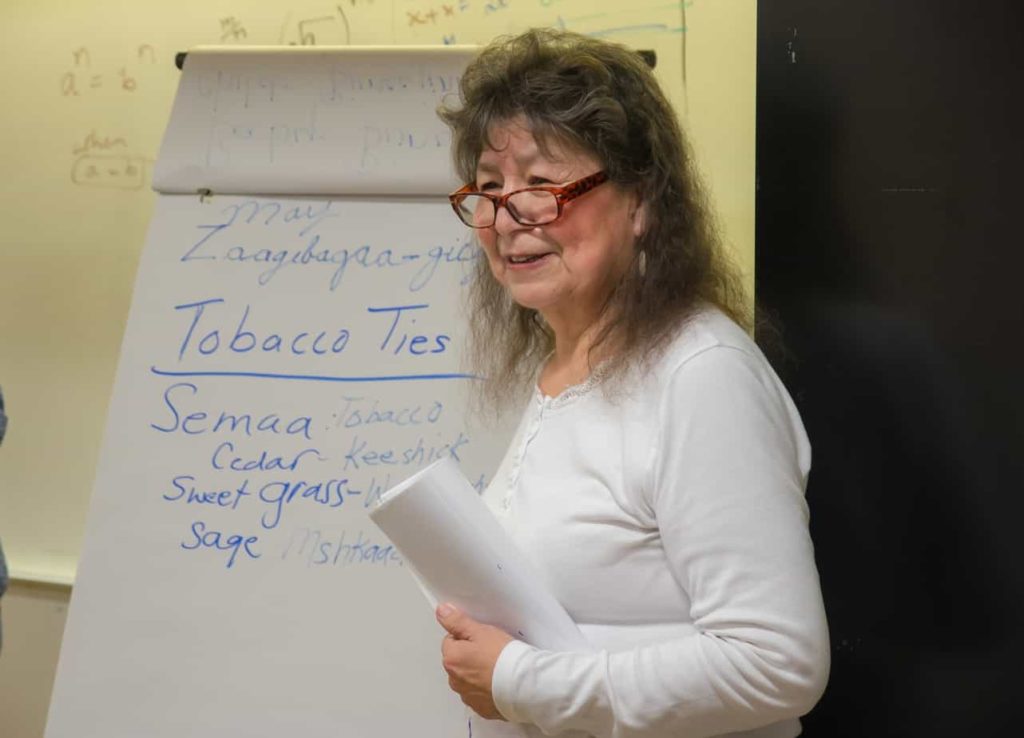

In the Ojibwe class, more than 20 students sit at tables with workbooks open and jot down notes while listening to instructor Monica Benson talk.

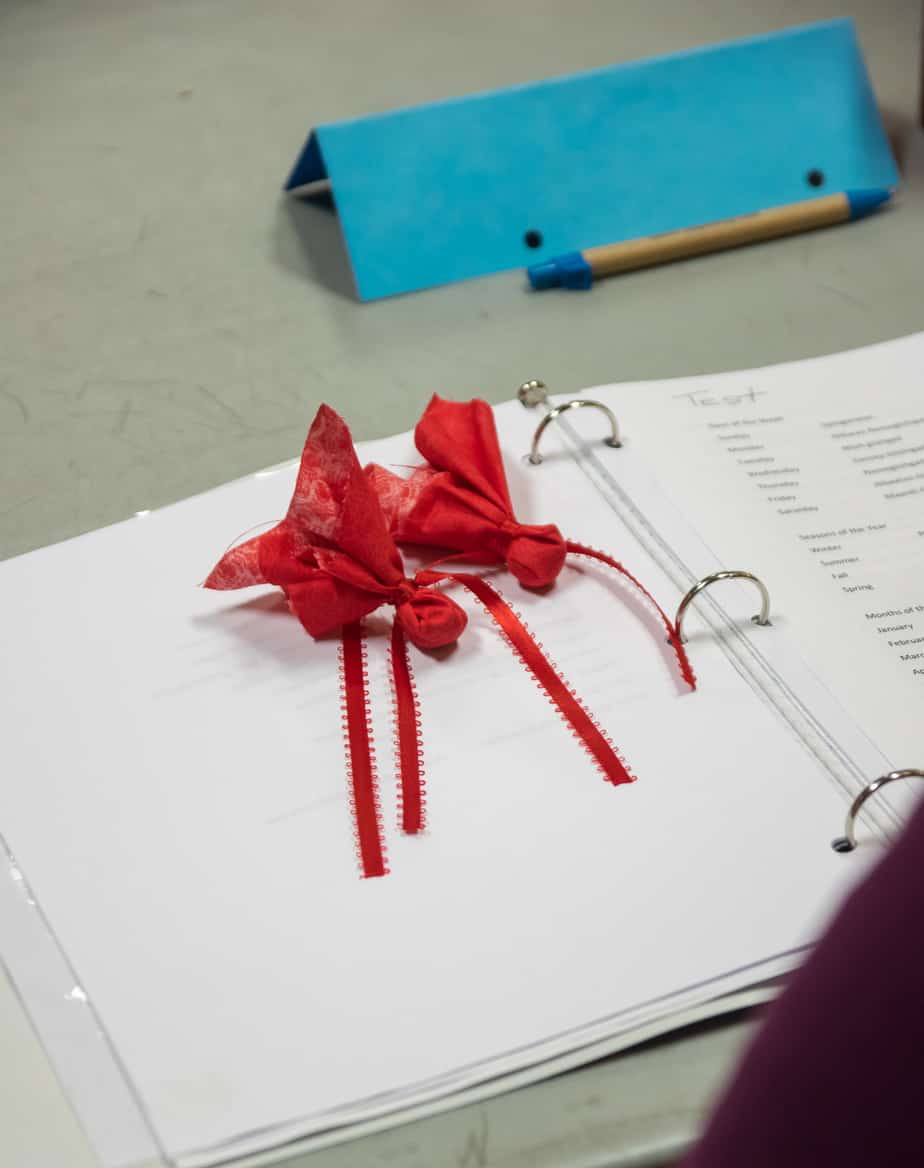

Benson sounds out the word for tobacco. “Semaa,” she says as she writes the word on a large sheet of paper with a Jiffy marker, and the students write in their notebooks.

One student stands and addresses the class. He says Indigenous people in North America aren’t the only people who revere tobacco; that some nations in Africa also consider it spiritually significant. “We’re part of something bigger,” he says.

The man is one of three male students in class; the other students are all women. This doesn’t surprise Dorothy Visser, who teaches the Cree class down the hall.

Children first hear a language from their mothers, she says. “They look after the children. They are more motivated to learn the language, to speak the language so they can teach their children.”

Visser was born on the Saddle Lake First Nation in central Alberta. Called the Amiskwacīwiyiniwak, Saddle Lake is part of the Plains Cree. She says she specifically teaches the Y-dialect of Plains Cree. She’s spoken her language all her life, she says. “I learned it at home before I went to residential school. I never spoke a word of English before I started school. It has always been Cree.”

Visser moved to the Lower Mainland from Alberta in 1981, and has taught Cree in schools and in friendship centres since.

Teaching Cree educates Cree people about the epicentre of their identity as a people, she says. But it also helps repair the damage done to language by Indian residential schools, where students weren’t allowed to speak their language. “The parents spoke mostly English to their children because the children didn’t understand anymore,” she says. “I always spoke my language with family, my siblings. I’ve pretty much spoken it all my life. It’s Plains Cree, it’s Y-dialect.”

Visser got the call from the Pacific Association of First Nations Women to teach the Cree class at Native Education College in September. The class started with 34 students, but five have dropped out since, and there is a waiting list, she says.

There is a serious side to learning the language, but Visser says that fun and laughter are part of every lesson. The class isn’t just about repeating words, Visser says. It’s about using those words to have conversations with each other in Cree. “I have them talking to each other in the Cree language, especially the introductions and where they’re from.”

The students are off to a good start. The class recently had a test in which they all scored perfectly, so they’re getting to know the language, and themselves.

“It’s their culture and it’s their identity, the Cree nation,” Visser says.

Outside of class, a bespectacled Allie Kidd is wearing a t-shirt that says “Born Cree,” and her nine-year-old son Michael holds a drum. Identity is why Allie, 36, is taking Cree lessons. She was taken from her family as part of the Sixties Scoop, and adopted into a home away from her First Nation, with no connection to her culture. Taking Cree lessons is a way to take back what was taken from her, she says.

Hearing herself say her first Cree words in class was “extremely emotional,” Allie says.“I feel like I’m speaking from my heart, and I feel like I’m speaking something that there’s a part of me that’s kind of known all along,” she says. “It feels almost in a way like I’m coming home. That I’m being reconnected to my family, and my ancestors and the Creator.

Her son accompanies her to every class, ensuring he’ll always know who he is and what he’s a part of. “I’m also blessed to be able to have my son learn it with me, so we’re getting two generations in one go,” she says.

Larry Nicholson didn’t learn to speak Cree growing up in the Montana Cree Nation in Alberta, but later took Cree in university. A Vancouver resident for the last 20 years, Nicholson jumped at the chance to pick up Cree again. Learning it in fellowship with other Cree people gives it more meaning, the father of two says.

Nicholson has a particular affinity for Plains Cree, he says. “It’s actually more beautiful to hear the fluent speakers because where I’m from in Alberta it’s the Plains dialect, and it’s very soft, and it’s very lilting, but it’s beautiful and it’s instantly recognizable,” he says. “It’s a real comfort sound to hear somebody speak — a fluent speaker speak.”

‘There’s hope that we’re going to save our language’

Back in Ojibwe class, the students are just finishing their lesson under the tutelage of instructor Dorothy Eastman.

Born on the Little Sask First Nation in Manitoba, Eastman, 73, grew up speaking Saulteaux, which is a branch of Ojibwe. She later moved to a Cree community, and learned to speak it as well.

A Vancouver resident for 40 years, Eastman was approached in September and asked to teach the course. She speaks Ojibwe fluently but never taught it before. Despite this, she felt obliged to accept.

“I thought, ‘I get to teach my language.’ Then I was apprehensive, I’ve never taught before,” Eastman says. But she knows how important it is to preserve the language. “The need is great, greater need to preserve our languages,” she says. “I feel guilty because I didn’t teach my children.”

When she saw how many students rushed to sign up for the class, she says she was “floored, but I knew the need was there. I said, ‘This language is going to die like other languages.’ Then this course started and I thought, ‘There’s hope that we’re going to save our language.’”

Teaching students how to speak Ojibwe in a school classroom evokes a certain sense of pride and irony in Eastman. She recalls her own experience speaking Ojibwe in residential school when she was seven. She asked her sister a question in Ojibwe and a teacher beat her with a yardstick for it.

“I was thinking when I was asked to teach, I thought, ‘65 years later I get to teach. it wasn’t beaten out of me then,’” Eastman says.

Ojibwe student Kaen Seguin can relate to Eastman’s childhood story. Her late grandmother attended residential school, the fallout from which trickled down and impacted her. “It ‘worked,’ for lack of a better term, and so she never taught her children — my father included — how to speak their language. So I’m just sort of reclaiming our stolen heritage,” Seguin says.

She now knows how to introduce herself, ask how you are, and say where she is from. Seguin first thought of her grandmother, she says, when she started speaking Ojibwe. “When I first hear myself repeating words in my language it was great — short answer, it was amazing I felt very proud,” she says. “Just very connected to my grandma, and I wish she could hear me.”

Down the hall, nine-year-old Michael Kidd strikes his drum with a padded stick and sings a Cree welcome song with Visser’s help. The two sing alone at first, but the rest of the class soon joins in, and accompanies them until the end.

Eastman says she felt it in her heart and soul when she heard him sing.

“Even a baby, when you hold a baby and you’re at the pow wow when you hear a drum, the baby starts wiggling around like it wants to dance,” Eastman says. “It’s beautiful — the language, drumming, and that learning our ways.”

Expanding conversation circles

The eight-week classes finished in early December and another session starts in January, says Diana Day, adding that there are plans to expand the program.

Day wants to meld graduates from the first session into the new one. Doing so would give students added opportunity to pass on what they know, converse and reinforce what they learned.

She is also working on a plan to have graduates work with a Downtown Eastside agency in Vancouver to seek out fluent Cree and Ojibwe speakers who are living through hard times in the area.

“It’s important to connect with our people from home and give language opportunities to them,” Day says. “We want to bring them into conversation circles with our grads.”

The program is already bearing fruit. Day was at a business meeting recently when she saw a student who was also there get up and introduce themself in Cree.

“Our language is alive, and it’s just starting to thrive,” she says.[end]

[factbox]

WATCH OUR VIDEO

Here’s Michael Kidd learning to drum and sing in Cree, and his mom and some of their classmates talking about how much learning their language means to them.

[/factbox]

This piece was edited by Robin Perelle. Sign up here for our Urban Nation newsletter.