It’s no secret that Indigenous kids in Canada are grossly overrepresented in foster homes and group homes, and that this is a product of deliberate government policies to stamp out Indigenous culture.

For more than a century, Indigenous children were ripped from their homes and sent to live in residential schools or with white families. They were cut off from their land, their language, their songs and stories and elders, and all the things that gave them a sense of belonging and identity. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and former Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin called what Canada did “cultural genocide.”

Today this trauma is felt not only by survivors of residential schools and the Sixties Scoop, but also by their children and their children’s children. Far too many Indigenous children remain in government care, cut off from their culture.

In British Columbia, according to the Ministry of Children and Family Development, 64 per cent of the 6,441 kids in government care were Indigenous as of Oct. 31, 2018, even though Indigenous youth under 15 make up just 10 per cent of the province’s total population under 15. Of those 4,132 Indigenous kids, about half are cared for by Delegated Aboriginal Agencies authorized to deliver their own child welfare services to Indigenous people; the rest are directly under the ministry’s care.

By law, the ministry is supposed to support the kids in its care to develop a sense of cultural identity and belonging, to help them connect with their extended family and community. In 2003, it introduced the Roots program. The goal, according to a report from B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth (RCY), was to “ensure that Aboriginal children in the care of the ministry have a plan that will respect and preserve their identity with ties to their family, Aboriginal community and heritage.”

But it takes time to “respect and preserve” cultural identity. And social workers say they just don’t have it. It’s already “almost impossible” to meet basic standards, they told the RCY in a December 2018 report.

Social workers say they’re already juggling huge caseloads and don’t have the resources to extensively research a child’s lineage or accompany them on trips to their traditional territory. They need support from Indigenous Roots workers to ensure Indigenous kids’ rights to culture are met.

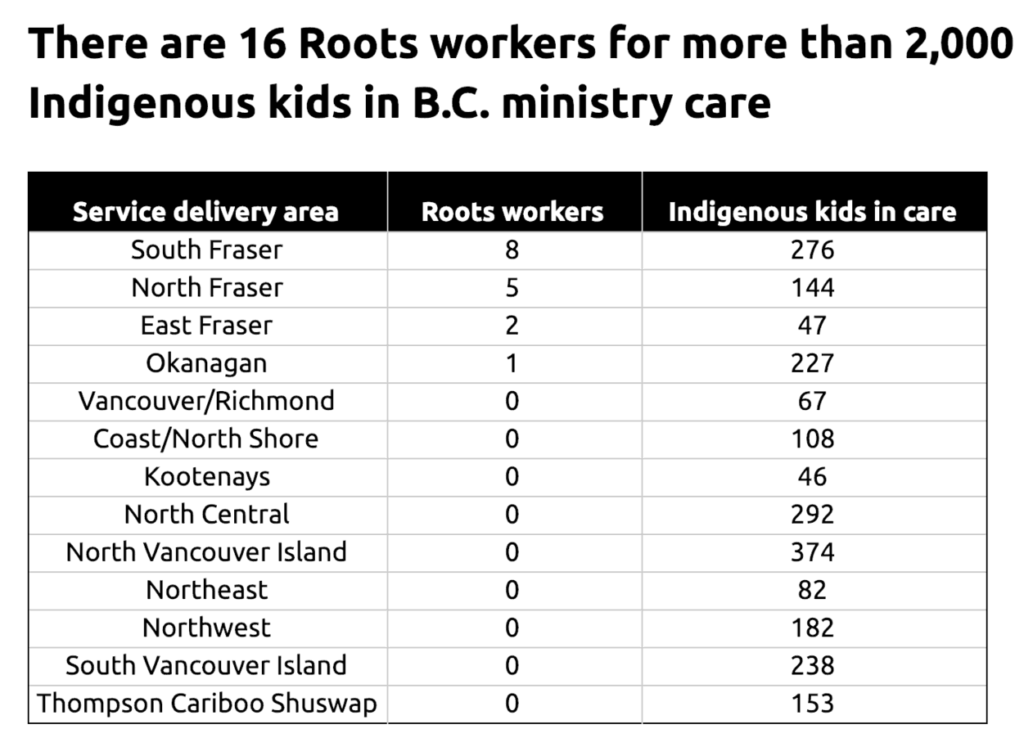

So why are there just 16 Roots workers for more than 2,000 Indigenous kids in the ministry’s care?

What exactly does a Roots worker do?

Caren La Fontaine is one of five Roots workers in the ministry’s North Fraser district. Over the phone, she says a big part of her job is supporting kids to develop a sense of cultural identity.

This happens in many different ways, says La Fontaine, who is Lakota and comes from Wood Mountain First Nation in Saskatchewan.

Roots workers help Indigenous children figure out where they come from and if they qualify for Indian status. They trace their family lineage and create genograms. And they organize and accompany kids on “homecoming trips,” so they can meet their extended family and “touch the ground that their ancestors come from.”

“We’ve been doing quite a few of them the past year,” she says. “We usually try and set something up where the community has something planned for that child… They’ve been blanketed; they’ve had naming ceremonies.”

La Fontaine says she loves taking Indigenous youth out on the land, and “just seeing their innate connection — that’s already there through their blood memory — shine through.”

She works with her team to host monthly, often land-based, cultural events: “Anything from medicine-picking up in the Okanagan and Merritt areas, to beading, to sweat lodge ceremonies.” Every summer they also try to take a group of youth on the Pulling Together canoe journey.

They host workshops, too, where new foster parents can learn from elders who have experienced residential school, youth who’ve been through care, and Indigenous foster parents. “I usually cook traditional food for each session and give them the experience of tasting it and how to cook it, so they can take that sharing back into the home and support the child with that,” she says.

And then there’s the permanency piece: La Fontaine works collaboratively with social workers and Indigenous communities to find extended family for kids, in case they can’t be returned to their parent(s), and to help them build more family connections. She helps social workers develop custom cultural care plans for every child in care.

This work takes time and sensitivity. “Not all families want to directly work with a social worker right away,” La Fontaine says, “because of historical trauma and issues between the ministry and Indigenous communities and families.”

“There has to be a building of the relationship,” she says. “As Roots workers, we help support that and bridge that gap.”

‘A big part of our role is educating ministry staff’

All five Roots workers in North Fraser are Indigenous, La Fontaine notes, and they all bring different knowledge and connections to community. “A big part of our role is educating ministry staff,” she says, “on how to work collaboratively.”

Chris Rambaran can attest to this. He identifies as a visitor in Coast Salish territory, whose ancestral roots trace back to India and Mauritius. He spent three and a half years working for the ministry, first as a child-protection worker and then as a guardianship worker serving vulnerable and at-risk youth in the Downtown Eastside. He’s also a former youth in care.

When an Indigenous Roots worker joined his Vancouver office, Rambaran says he noticed their office culture start to change.

“There was more artwork, there were medicines around. She would be leading smudges. She would be bringing in that lens and that perspective when we discussed complex cases and situations. She just brought a new energy into the work.”

Rambaran says his mostly non-Indigenous colleagues appreciated it when the Roots worker led them in opening ceremonies and prayer. As non-Indigenous people serving many Indigenous families there was a recognition of the importance of ceremony and protocol, but the social workers didn’t feel equipped to lead themselves because they felt “they would be misappropriating,” he says.

The Roots worker also taught Rambaran about the diversity of Indigenous cultures and what it was like for her to be bullied in high school — how she used to fear getting followed home. And she taught him to speak some Cree.

Having an Indigenous colleague on their team had a “huge impact” on families, too. “It balanced out the power more,” he says. It was no longer “us versus them.”

And, of course, he deeply valued all the hard, “rabbit hole” work she did to find extended family for Indigenous kids — the endless phone calls and all the digging.

“It’s important because social workers with their caseloads and involvement in crises — they don’t have the capacity to take on a lot of that work,” he says, “and unfortunately it gets put on the back burner.”

16 Roots workers for more than 2,000 Indigenous kids

If Roots workers play a much-needed role in the child-welfare system, why are there so few of them in B.C.?

According to a spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Children and Family Development, the ministry “currently employs 16 Roots workers.”

That’s 16 Roots workers in a province with about 2,000 Indigenous children directly under the ministry’s care.

In North Fraser, where La Fontaine works, there are five Roots workers and, as of May 2018, there were 144 Indigenous kids in the ministry’s care. That’s approximately one Roots worker for every 29 kids.

In other areas of B.C. like Vancouver, Richmond and the North Shore there are no Roots workers at all.

The Discourse requested an interview with Minister Katrine Conroy to ask if there are enough Roots workers to meet the needs of Indigenous kids in the ministry’s care.

Spokesperson Shawn Larabee replied via email on Dec. 11, to say the minister is “the only one who can appropriately speak on behalf of the ministry in this regard. I know she’s very busy, but I’ll let you know if she has a moment to speak with you.”

When The Discourse followed up six days later, Larabee said, “Minister Conroy is not available for an interview.”

When The Discourse followed up again in early January, Larabee reiterated, “Unfortunately, Minister Conroy is unavailable for an interview.”

The ministry did, however, provide a statement in late December: “Because we know that connecting children and youth to their communities and culture is very important to their wellbeing it is expected that, regardless of what specific job any staff member working with a child or youth is doing, they are promoting and nurturing connections.”

The ministry says the total absence of Roots workers in some regions is not a problem.

“While guardianship workers and roots/family finder workers have a greater focus on strengthening a child or youth in care’s cultural connections, all social workers and foster parents are responsible for promoting this,” the ministry says in its statement.

“We have increased the number of Roots workers over the past few years and there are no plans currently to add more,” it adds.

The Discourse asked Rambaran what he makes of the ministry’s position.

“I think that’s a huge issue,” he says. “Yeah, sure, social workers are responsible and so are foster parents and everyone involved in the child’s life — but is that [cultural work] really being prioritized? It doesn’t seem that way.”

“Social workers don’t have the capacity,” he says.

Asked whether she’s got enough work as a Roots worker to keep her busy, La Fontaine laughs. “There are weeks where I work six days,” she says. “Our work is ongoing; it’s never-ending.”

Jennifer Chuckry is a former Roots worker who now manages a team of social workers as the executive director for Surrounded by Cedar, a Delegated Aboriginal Agency in Victoria.

She says at her agency they cap social workers’ caseloads at 20 kids, and even then it’s “almost impossible” to meet standards.

When social workers aren’t helping children to manage “the day-to-day stuff,” they’re managing crises such as foster-placement breakdowns and mental health issues. And they’re trying to connect with a child’s nation, family and extended family on top of that, she says.

“I think it’s incredibly difficult for social workers to be able to address all of those needs as one individual, and so any time there can be additional support, such as Roots practitioners or family finders, that’s alleviating some of that pressure from the social workers.”

Chuckry calls Roots work vitally important.

“We see the impact of disconnecting our people to identity and family and land. We’ve seen all of that, and we know what the outcome is,” she says.

“If we’re really going to put our money where our mouth is — and we’re going to say, you know, kids in care have a right to their cultural identity — then you have to create the services to able to support that.”[end]

This piece was edited by Robin Perelle. Sign up here for our Urban Nation newsletter.