On the night of Aug. 12, 1913, a riot erupted in the streets of Ladysmith. Between 200 and 400 striking coal mine workers and supporters swarmed the Temperance Hotel on High Street, which housed some of the miners who were working in defiance of the strike. The strikers threw rocks through the windows of the hotel, shattering the glass. A small bomb detonated inside, shaking the walls. Hours later, a second explosive blew off the hand of Alex McKinnon, a known strikebreaker, as he attempted to remove the bomb from the room where his children slept.

It’s hard to imagine the scene, in a town that people know today for its quiet charm. The riot was one of several violent confrontations at mines and mining towns on Vancouver Island during the Great Strike of 1912-1914, when the United Mine Workers of America fought for better conditions for workers and companies resisted. Coal mining was brutal and dangerous work. Union records suggest that at least 373 men died in underground gas explosions in Vancouver Island mines in the three decades leading up to the strike.

Amid the violence that August, the Attorney General of Canada called for more than 1,000 militiamen to march on Vancouver Island coalfields and communities between Cumberland and Ladysmith and seize control. They arrived in Ladysmith on August 15 and arrested 58 people.

Ladysmith coal history still echoes

That history may feel lifetimes away, but the echoes still sound. Earlier this month, Western Forest Products reached a deal with more than 3,000 striking workers on Vancouver Island in a difficult dispute that dragged on for nearly eight months. Union leaders with United Steelworkers Local 1-1937 say that improving worker safety was central to their concerns in the dispute. It took special mediators appointed by the B.C. government to get to a resolution.

More people should know about the coal miners’ strike, Eden Haythornthwaite tells me. Haythornthwaite is one of the organizers of an annual memorial for Joseph Mairs, who died in prison in January 1914 at the age of 21 after the militia arrested him for his role in the Ladysmith riot. “People have things today that other people won for them, and they should know about that,” she says. “It takes ordinary people, becoming extraordinary. I think people are letting go of this history at their peril.”

Who was Joseph Mairs?

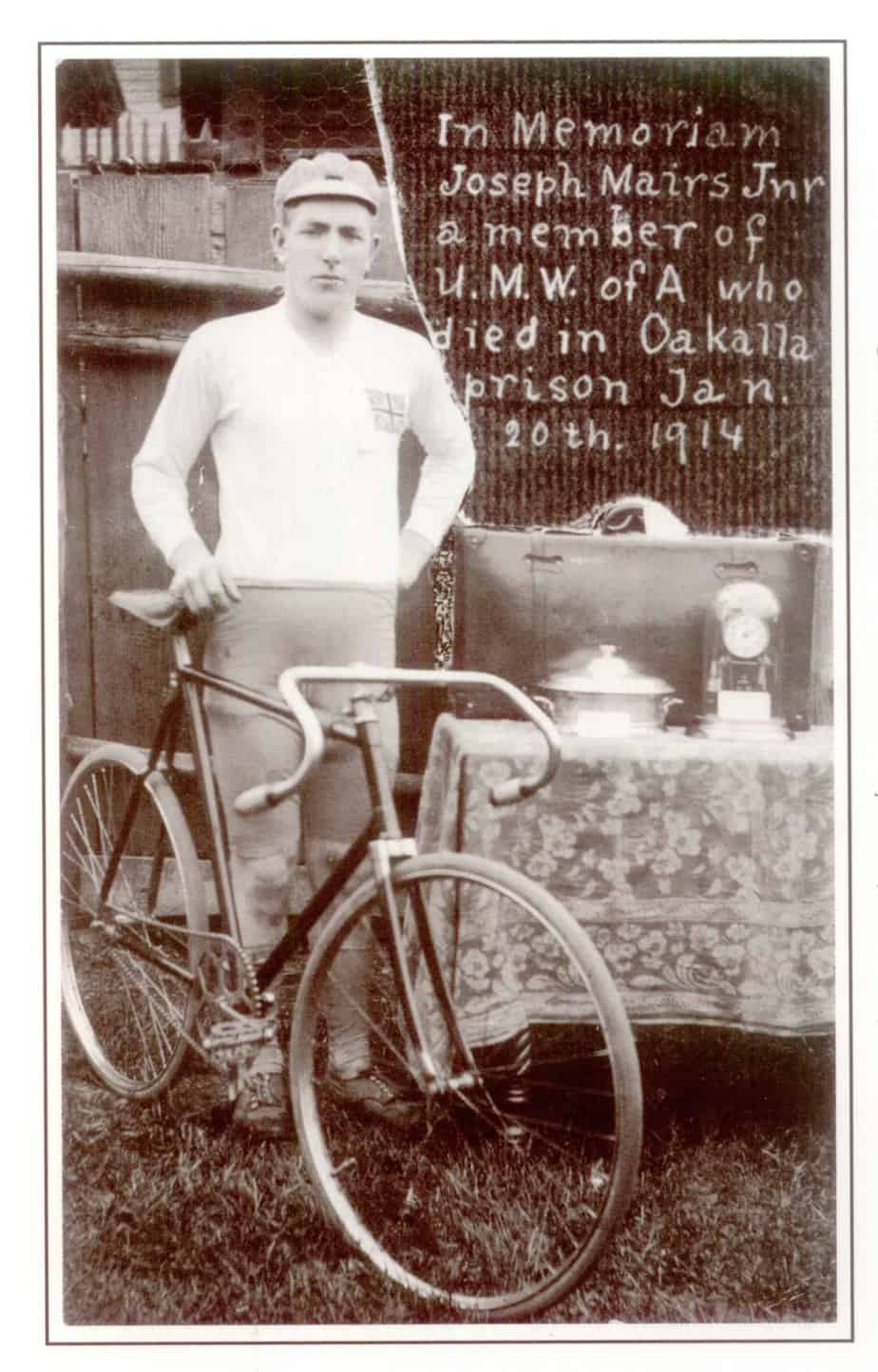

Joseph Mairs was an immigrant from Scotland who worked in the Extension Coal Mine, near Ladysmith. He was a “very ordinary young man” who liked to race his bicycle, Haythornthwaite says. The militia arrested him for throwing rocks during the riot and a judge sentenced him to a year in prison. But a few months into his sentence, he fell ill and, absent appropriate medical care, died.

According to an article in the Ladysmith Chronicle on Jan. 27, 1914, Mairs’s funeral was the largest ever held in Ladysmith, and the procession was a mile long. Haythornthwaite says that the United Mine Workers of America sold postcards with Mairs’s photo to raise money for a cairn at the cemetery in Ladysmith. The cairn remains one of the largest monuments in the cemetery today.

Want to learn more?

-

The Ladysmith and District Historical Society holds many records and images related to the Great Strike of 1912-1914. The archives are open Monday to Friday, 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. The museum is open by appointment during the winter.

-

When Coal Was King, a book by John Hinde, tells the story of coal mining and community organizing in and around Ladysmith.

-

This 1980 article by John Norris examines some of the local conditions that made organizing for worker rights particularly challenging for coal miners on Vancouver Island in the early 20th century.

-

This 2014 article by Daniel Schade looks particularly to the first-hand accounts of militiamen in its telling of the military intervention in the strike. [end]