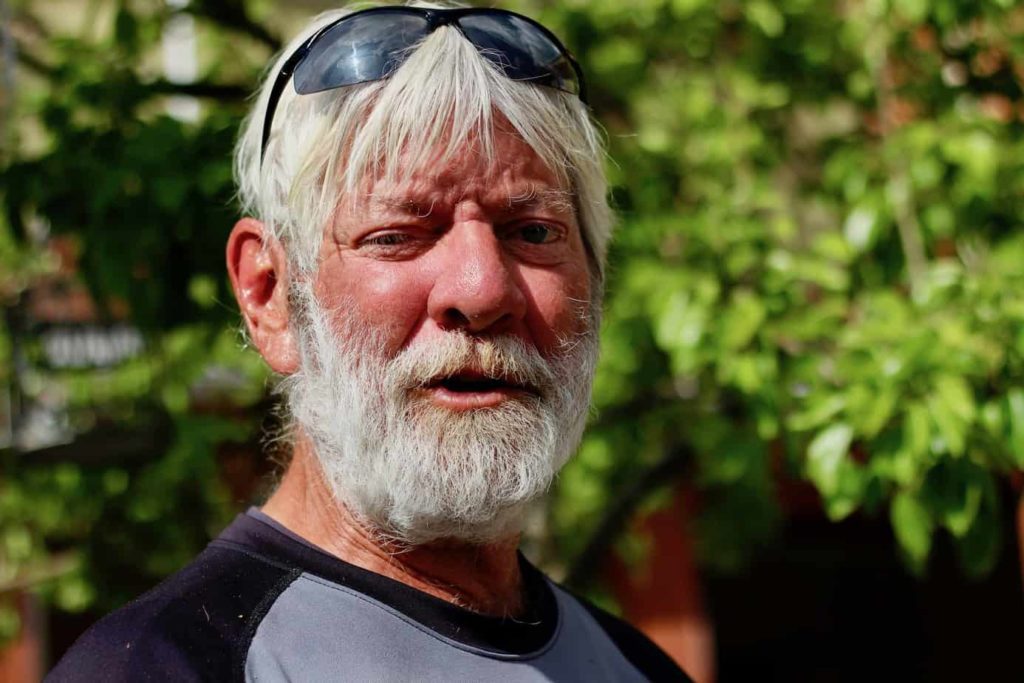

Dan Franklin would rather not speak about his experiences interacting with the RCMP in the Cowichan Valley — but he’ll talk about Jack MacNeill.

MacNeill has been mostly retired from the RCMP for more than a year— technically he’s still a reserve constable, which means he can volunteer for service if he wants to. But Franklin hasn’t forgotten his kindness.

Franklin got to know MacNeill, he says, at a time when he was struggling with depression. MacNeill worked with a program that pairs an RCMP officer with a mental health nurse from Island Health in order to reach out to people with mental health or substance use issues and connect them with services.

Franklin says he was impressed, both by MacNeill and the mental health nurses he worked with in the Car 60 program. “They went above and beyond in helping people. They really cared. They were there for anybody that needed it, and probably people that needed it more so than I did.”

Lately, Franklin’s been living at Warmland House in Duncan. It’s temporary, he says, just until he can figure out how to transport the trailer he still owns and move back into it. He’s 63 and “getting younger,” he says, thanks to the swimming, stretching and martial arts training he’s dedicated himself to.

He says that MacNeill and Car 60 really helped him. The program has the connections to refer people to whatever services they might need, he says. But the biggest thing for him was “just talking.”

Mental health calls to police on the rise

RCMP officers in the North Cowichan/Duncan region of southern Vancouver Island are increasingly being called upon to deal with people in mental health crisis.

The number of incidents where officers brought people to hospital because they were in mental health distress, and deemed a danger to themselves or others, jumped 40 percent between 2015 and 2018, from 217 to 303 incidents, according to statistics provided by the RCMP.

“Our guys were being run off their feet responding to things that weren’t necessarily criminal in nature, but mental health in nature,” says MacNeill.

Cowichan is not unique. Police departments across North America say they have seen an uptick in calls to respond to people in mental health crisis. A 2016 report of the Canadian Mental Health Association found that police have become the by-default first responders of the mental health system because fewer people are being institutionalized long term, and not everyone is finding the support they need to live successfully independently.

Staff Sergeant Chris Swain, a supervisor of the Car 60 program, says he’s seen big changes in the Cowichan Valley in the six years he’s been here — changes that have left more people struggling.

The rate of homelessness is up, he says, and the opioid overdose crisis has hit this area hard.

“We’ve definitely seen an increase [in mental-health calls] because of those things,” he says. “A lot of people who are falling in those categories suffer from mental health-related issues. And a lot of times they go hand in hand.”

But there are broad socio-economic factors at play, Swain adds, and the increase in mental-health calls can’t be attributed to just one thing.

According to Island Health data, Duncan and neighbouring communities have higher rates of depression, anxiety, suicide and drug-related deaths compared with the rest of Vancouver Island. The rate of hospitalization of children for mental health reasons is higher, too. And staff at Cowichan Valley Youth Services say they’ve seen an increase in youth seeking mental health support.

James Tousignant, the executive director of the Cowichan Valley branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association, traces this disparity back to the decline of resource industries in the 1990s and early 2000s, which led to sawmill closures and massive layoffs.

And, in the last 10 years or so, “this place has been discovered as a very nice place to buy a little mini hobby farm if you’re coming over from Victoria or Vancouver. You can sell down there and buy something that’s amazing up here,” he says. “The price of housing went from stagnant to through the roof.”

This combination of declining incomes and an increase in the cost of living manifests in more visible and acute struggle with mental health and substance use, Tousignant says. For First Nations people, there are additional factors, including racism, stigma and the legacy of residential schools, he adds.

Swain says the numbers of mental health calls his detachment receives is similar to what the RCMP detachments in Prince George and Kamloops see, which each serve significantly larger populations.

This surprises him, he says, and he’s not sure how to explain it. “We’re still wrapping our head around it.”

Trying a different approach

The spark for the Car 60 program came from a presentation to a Cowichan Valley Regional District committee by Carol-Ann Rolls of Cowichan Valley Community Policing, says Kate Marsh, a councillor with the Municipality of North Cowichan.

Marsh pushed the municipality and RCMP, beginning in 2013, to initiate a program in the model of others tried elsewhere, like the Vancouver Police Department’s Car 87 program, which was first tried in 1978 and formalized in 1987.

“The RCMP dragged their feet a little bit, but it wasn’t because we didn’t believe in the program,” says MacNeill. Instead, police wondered how they would staff it, with resources already stretched. “We were at a stage where we had like 10 percent of our personnel were off sick, or mat leave, or stress leave.” He credits Marsh’s persistence for the eventual rollout of the program, which was in operation by 2017.

In the early days of the program, MacNeill and the nurse he worked with met and each brought a list of names. MacNeill’s list was made up of people who police frequently dealt with for mental health or substance use issues. The nurse brought names of people with known mental health concerns who perhaps hadn’t been heard from in a while, and weren’t making their appointments, says MacNeill. They compared notes, and then they went to check on people.

“We would knock on doors, and we would try to hook them up with whoever they needed to see,” he says. “To see the cop on the doorstep, people get really defensive. They think, ‘Uh oh. I’m in trouble, I’m going to jail. I’ve done something wrong.’ So a lot of times there was pushback, there was a lack of openness, a lack of communication. But over time that changed, especially with the street people.”

It started with one day of outreach per week, then went up to two. Now, it’s back to one day of outreach work and patrols, with a mental health nurse also available during the daytime on weekdays to jump in with an officer to respond to people in crisis, says Swain.

He says a benefit of the program is that the officer and nurse can get people the help they need without necessarily taking them to hospital, which is time consuming. Some individuals who have been in contact with the program, he says, have gone from needing frequent police intervention to none at all.

And RCMP officers, even beyond those directly involved with the program, are learning new skills to interact with people in crisis, Swain says. “We’ve all been on calls where the Car 60 program and the nurses are attending, and we can learn from the nurses, right? And I’m sure it’s a two-way street. I’m sure everyone is learning.”

Lisa Murphy, a regional director with Island Health, says the Car 60 program allows nurses to get to people they wouldn’t otherwise reach, because they have the protection of an officer behind them. The collaboration between Island Health and RCMP is good for both service providers and clients, she says.

“We really can’t speak enough to when those relationships amongst service providers are strengthened, how we all benefit from that. Because we bring different skills, approaches, different lenses to interactions, and to the table.”

Car 60 builds trust, community members say

Colleen Fuller, manager at the Duncan Foodbank, says Car 60 is the “best program.” The RCMP “used to come through this door — everyone would just bail out the front. It was comical. A lot of guilty consciences. And with that Car 60, and then just coming and having coffee, and sitting and stuff — now nobody bails when the cops come through. They’re fine. And it’s really spread through the force.”

Isabel Rimmer, an emergency room doctor and department head at Cowichan District Hospital, says she too has seen relationship-building between the RCMP in the Car 60 program and vulnerable people in Cowichan. She says she specifically remembers two individuals, brought in within a week of one another, both living in homeless camps.

“It was very moving to hear them talk about the RCMP officer that helped them in that Car 60 program,” she says. “In the context of that population and the general antagonism between that population and law enforcement, for the Car 60 program to have built up that degree of trust with these particular guys, who are about as marginal as you can come across, was very impressive.”

“I think it’s probably the only way of touching base with the most disadvantaged, the most disconnected, the most mentally ill, physically unstable, and psychiatrically unstable, and substance-addicted population,” she continues. “Car 60 goes to places where the people that can’t manage Warmland [the emergency shelter] hang out.”

One small part of the solution

Ask MacNeill about the successes of the program, and he’ll mention Lance De Bree. De Bree was “a bad son-of-a-bitch,” says MacNeill, in frequent trouble with RCMP. But after three years living on the street, De Bree says, he went for treatment for his substance-use issues, and recently moved into supported transitional housing in Duncan.

He had been overdosing a few times a month and “I just got sick of it. I was almost dead,” he says. “I just thought of my girls and them growing up without a dad. It was just a reality check.” He says he’s learning again how to live on his own, how to do the regular life stuff.

Now, MacNeill and De Bree occasionally volunteer together, cleaning up the downtown area in the mornings before businesses open. “Everybody gets a laugh with that,” says MacNeill. “The cops say, ‘Jack, what the hell are you doing with Lance?’ And the street people are saying, ‘Lance, what the hell are you doing with him?’”

De Bree knew MacNeill through the worst of times, and it wasn’t like his relationship with other cops, he says. “He’s somebody I could relate to. He was a straight-shooter, eh? He’d never B.S. me. When I was screwing up he always let me know,” he says. “If I ever just wanted to talk, he just sat around and talked.”

“I don’t get too judgey with people that are messed up,” says MacNeill. “Everybody is messed up for a reason. I think that maybe kind of rubbed off on people. They realized that, ‘MacNeill’s not a prick, and if I do something bad, I might get arrested, but he’ll treat me with respect.’”

“When I was a very junior officer, my trainer said, ‘Jack, three things you have to do to do your job well. Be firm, be fair, be friendly.’ It’s so simple,” MacNeill says.

Car 60 can’t solve everything but it’s a good start, he continues. “Car 60 is putting their finger in the holes of the dyke. It’s an uphill battle, for sure. But it’s one small part of the solution.”

Constable Kim Granneman has been at the helm of the Car 60 program since November 2018. She’s passionate about the work, and says she sees it helping people who are in mental health distress. “It’s obviously a confusing and scary time for them, and having somebody be able to talk to them and reach out to them is so beneficial. A simple conversation with somebody who’s homeless can change their day, and their view of police.”

The outreach work is a “total shift” from normal policing, Granneman says. ‘You have to kind of put aside your enforcement ways and really focus on what’s best for that person.”

But it’s important work and she’d like to see more of it, she says. Granneman would like to see a full-time mental health liaison in every RCMP detachment. “My goal would be to have one member strictly for mental health, working alongside a crisis response nurse.” [end]