On a rise of land just behind Lake Cowichan Secondary School, there is a cluster of 99 modest houses built during the late 1940s. Today, this 32-acre development is a well established part of the Town of Lake Cowichan, but in 1946 it was a treed parcel of land outside the town’s municipal boundaries.

The homes resembled similar publicly-built rental developments constructed across Canada between 1941 and 1949. With workers and veterans struggling to find housing, Wartime Housing Limited (WHL), a federal crown corporation, organized the 100 Houses development project to address the dual post-war crises of housing and building material supply. Lake Cowichan needed housing for workers in the forest industry, and Canada and the world needed lumber for post-war reconstruction.

The 100 Houses in Lake Cowichan are a unique part of the Town’s development, and also part of a much larger story about how public housing provided a solution during a national housing crisis. Today, experts say this wartime project — and those similar to it — could be looked to as an answer to our present-day crises of housing and climate.

A national housing crisis

The Great Depression of the 1930s forced the federal government to get involved with the housing market. Ottawa took an indirect approach, using policy and a financial carrot and stick to encourage private development of housing and increased home ownership among the middle class of Canadian society, according to historian Jill Wade. However, by the start of the Second World War a national housing crisis was underway, made possible by a lack of building starts during the 1930s and a significant amount of outdated and dilapidated supply, especially in major urban centres like Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. For example, many homes across the country still had no central heating or plumbing.

As the war effort ramped up through the early 1940s, many people migrated to participate in war work, worsening the housing crisis. Low to moderate income Canadians were identified by the House of Commons in Ottawa as most in need of housing. In response to growing demands for direct federal intervention from community groups, veterans’ organizations, politicians and unions, the federal government created Wartime Housing Ltd. in 1941. Wartime Housing joined with provinces and municipalities to acquire and develop land to house workers involved in wartime industries, especially those working in the production of weapons and equipment.

Veterans and communities demand housing

Although the war was won in 1945, the housing situation further deteriorated when more than half a million people serving the war effort were demobilized and a post-war baby boom began. Veterans groups protested across the country.

“We are in a position to realize better than any other organization the desperate situation in which veterans find themselves,” said Maj. Oscar Erickson of the Citizens’ Rehabilitation Council of Vancouver in a 1946 Vancouver Sun article. “The returned men not only need accommodation, they have to be able to get it at a low figure.”

The situation in Lake Cowichan was no different.

“For the V shaped pattern of communities extending up either side of the lake from the pioneer settlement at the foot — now a village municipality — is feeling the pinch of the very products of its labours, namely housing” an article in the paper, the Cowichan Leader, said. “Commercial and domestic structures are appearing around every corner and in the ribbon-centre affectionately known as town, but the needs of the working population in the area remain far from satisfied.”

To meet this need, Wartime Housing Ltd. shifted its primary focus from housing for war workers to housing for veterans and their families. Local committees made up of politicians, advocates and business leaders identified potential projects that were facilitated by the crown corporation’s team of managers, architects and planners. Projects on Vancouver Island included suburban developments in Victoria, Saanich and Esquimalt, and housing for forest industry workers in Lake Cowichan and Port Alberni.

During and immediately following the war, supplies for building, particularly lumber, were managed and restricted by the federal government. Wartime Housing, however, gained priority access to building materials to facilitate its housing objectives. Projects in forestry communities ensured veterans could return to work in the forests and mills and meet the growing demand for lumber in Canada and abroad. At Lake Cowichan, Hillcrest Lumber Company owner Carlton Stone, alongside the owners of Western Forest Industries Ltd., championed a Wartime Housing project for the community.

Publicly built and maintained housing

In 1943, Carlton Stone moved his Hillcrest logging and milling operations from the Sahtlam area up to Mesachie Lake, just outside the village of Lake Cowichan. There, Stone made available supplies and labour to construct worker housing, a community hall, recreational facilities, an Anglican church and a Sikh Gurdwara, according to a 2007 article by Aimee Greenaway in the Cowichan Valley Citizen. By late 1946, Stone and other local advocates were successful in bringing the federal housing scheme to Lake Cowichan. In the book, Those Lake People, historian Lynne Bowen says Hillcrest workers cleared the 100 Houses site of logging slash and those who served during the war were given priority access to one third of the new houses. The development was to be dubbed “Parkstone” after Carlton Stone, but the name never stuck.

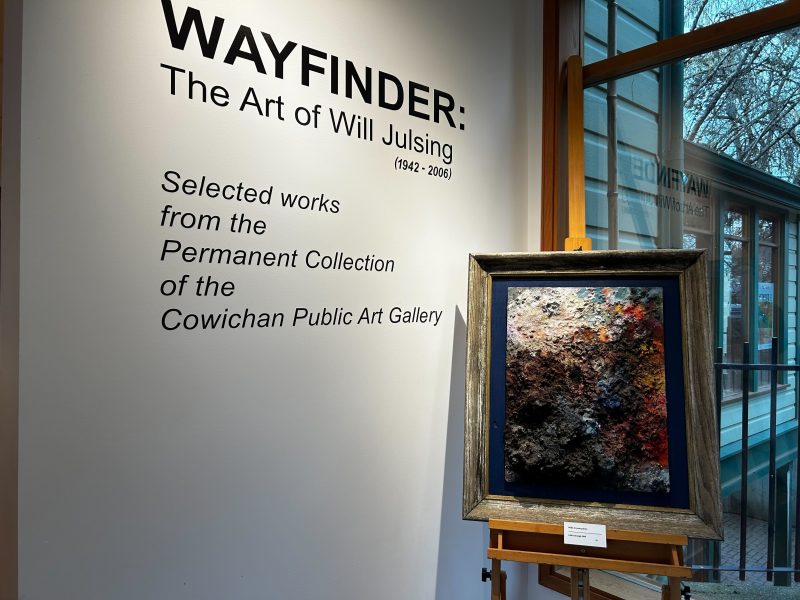

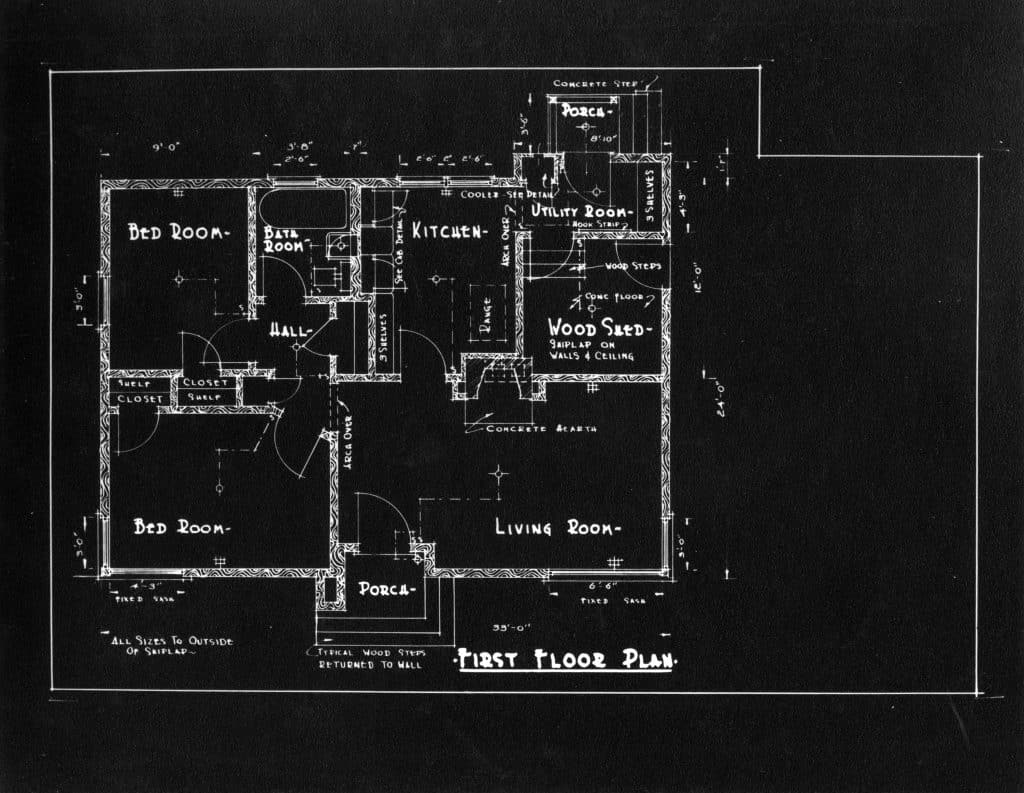

Construction of the 100 Houses began in the summer of 1947 with Garner Brothers of Duncan selected as the main contractor. Although the majority of archival records connected to Wartime Housing Ltd. projects are found at Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, the Kaatza Station Museum’s Wilmer Gold Photo Collection contains several black and white images of the development taking shape.

Geographer L.J. Evenden describes the wartime house as part of a Canadian cultural landscape.

“With thousands of dwellings having been built across the country within a few short years to a common basic design and standard of finish, and with the activity having been conceived and administered from a centralized crown authority, the citizens of Canada literally came to share a common housing experience.”

Like most Wartime Housing projects across Canada, the 100 Houses originated as affordable rental housing owned and maintained by government; a portion of the rent was forwarded to the Town of Lake Cowichan in lieu of property taxes. The first tenants received their keys to the two- and three-bedroom homes in March 1948.

A program of publicly built rental housing faced opposition from top federal bureaucrats and the real estate, building and financial sectors. Despite resistance, Wartime Housing Ltd. successfully built nearly 46,000 units of housing and could have transitioned to a publicly owned housing provider for all Canadians, but didn’t, Jill Wade explains.

“Although the federal government could have included housing in the emerging social welfare system through a WHL-inspired low-rental agency, it did not. The attitudinal changes making possible wartime advances in social security simply did not carry over to the housing field in any lasting way. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, long-range housing policy remained market-oriented rather than need related. In housing matters, the state was a ‘market welfare’ state.”

By the 1950s, Wartime Housing Limited was dissolved and their developments taken over by the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The 100 houses were put up for sale with priority given to the tenants. Facilitating private home ownership once again became the federal government’s housing policy objective.

Lessons for today

Reporter Michelle Cyca recently observed in Maclean’s that federal support for middle-class home ownership, rather than the construction of rental housing, is a primary reason Canada is facing a housing crisis. Now, as then, a lack of affordable rental housing is having consequences for urban centres and rural districts, including in the Cowichan Valley.

The coordination of human and economic resources made Wartime Housing Ltd. a promising response to the national housing crisis. In the book, A Good War: Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency, Seth Klein argues that the federal government’s intervention into Canada’s economy during the Second World War offers lessons for today.

The war forced the federal government away from a market-oriented approach to social and economic well-being. The historical example of Wartime Housing Ltd. could inform Canada’s response to the dual crises of climate and housing, suggests Klein, if a similar effort were made to build a national supply of carbon-zero affordable housing.

A walk through the 100 Houses neighbourhood shows the many different ways that generations of residents have modified the structures and made the former rental homes their own; but at their core, the houses provide a historical link to an organized and national effort to address a housing crisis.