Long-separated Quw’utsun belongings were welcomed back to the territory on July 26, taking a place of honour in the expanded Shawnigan Lake Museum. It was a moment of celebration for the community and the first step in telling the whole story of Showe’luqun, now known as Shawnigan Lake.

The expansion to the museum, which used to occupy the firehall next door, is the result of a multiyear, $3 million project to make room for more exhibits and provide a community hub for educational events.

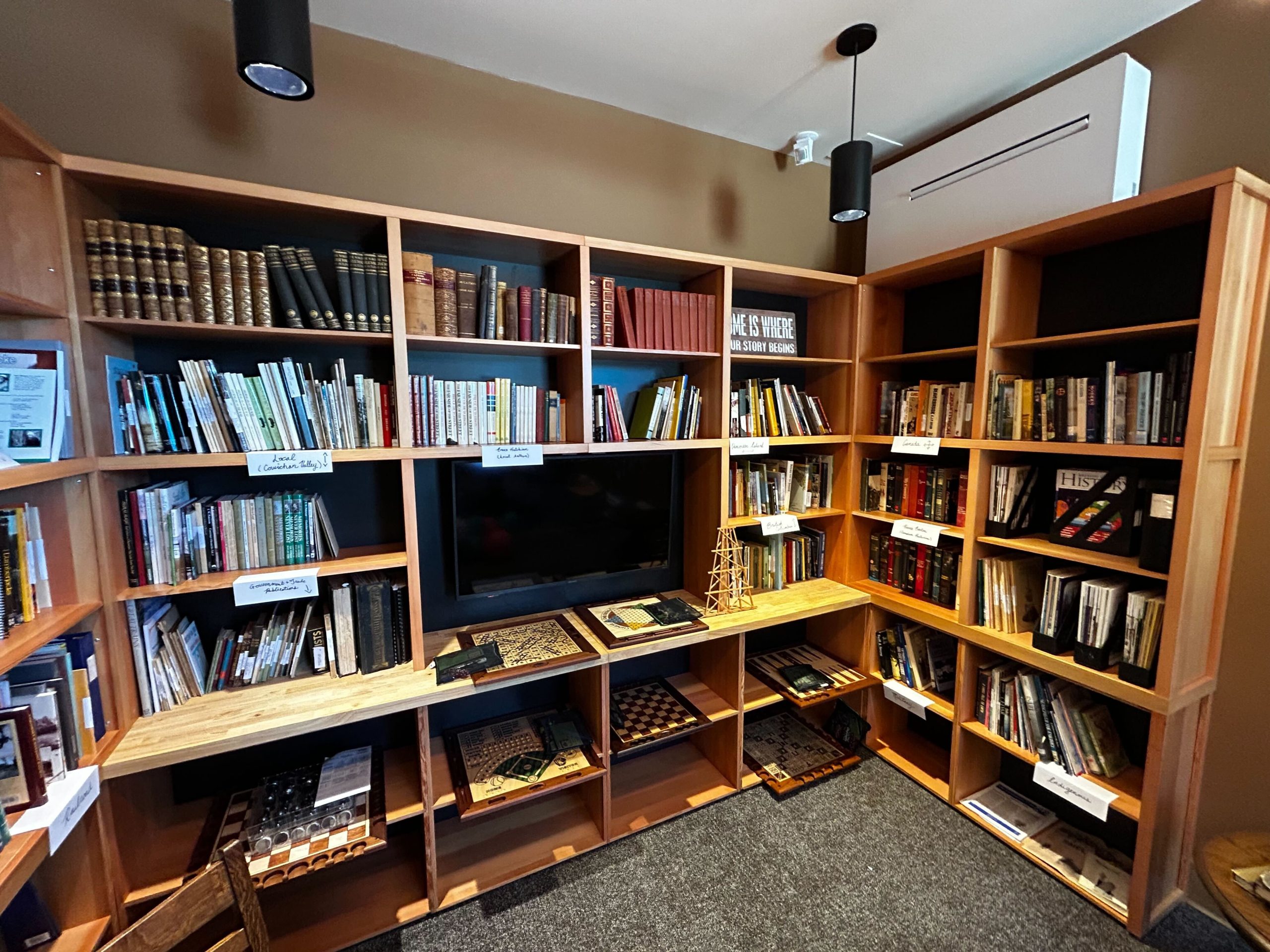

The new building includes a multipurpose event space, kitchen, expanded gallery and library where visitors can browse historical books and other materials related to Shawnigan Lake.

“The building was too small for the story of our area. Even though people think of Shawnigan Lake as a resort town, it really has a huge history,” said Lori Treloar, executive director of the Shawnigan Lake Historical Society.

And the history of the area just doesn’t start with colonial contact, noted Michelle Staples, Duncan mayor and chair of the Island Coastal Economic Trust. “That story goes back further. It’s going back to the original people of this land.”

A team from Cowichan Tribes, led by Chief Cindy Daniels, went to the Royal BC Museum to repatriate a selection of belongings that are now on display in the Shawnigan Lake Museum.

Thirty-eight belongings from across Quw’utsun lands (including the Gulf Islands) were repatriated and have been loaned out by Cowichan Tribes to be seen in the expanded portions of the museum, with more arriving by the day.

“It was a happy time. I feel like we were able to repatriate all of these items to share and tell our story,” said Johnny Crocker, specific claims researcher with Cowichan Tribes Lulumexun archaeology branch.

A space to tell the entire story of Shawnigan Lake

Expanding the gallery space was the perfect opportunity to add the history of Quw’utsun Mustimuhw (Quw’utsun Peoples) to the museum, which used Showe’luqun as a summer settlement, Treloar said.

Some of the Quw’utsun belongings on display were found in the areas around Showe’luqun, while others came from historic village sites including Kwa’mutsun (Quamichan), Xwulqw’selu (Koksilah) and S’amunu (Somenos).

Treloar said the historical society needed the help of Cowichan Tribes to incorporate this history in the museum.

“It’s inappropriate for settlers to try and tell the story of a nation, so it was thrilling to go to the Royal BC Museum with a contingent from Cowichan [Tribes] and let them choose what would be appropriate,” Treloar said.

Chief Cindy Daniels said she had never done anything like it before.

“It felt like an emotional day with really good feelings in that room, and you walked away just feeling so humble,” Daniels said.

One repatriated item held a particularly special significance to Crocker. He was at the Royal BC Museum with Daniels when he noticed a familiar name on the paperwork for a Cowichan sweater.

“On the paperwork, it said artist Mary from Galiano — which actually made me think about my own family because my grandfather, Johnny Crocker, had a sister named Mary,” he said.

The collection at the museum also includes items such as wooden fish hooks, stone and obsidian tools and a woven cattail mat used for insulation. The obsidian, which originated on the Oregon coast, showcases the extensive trade networks formed by First Nations people, according to Crocker.

On the day of the opening, Crocker told the Discourse that another delivery of belongings had arrived, though it hadn’t been set up for display yet.

“It was a very emotional time and by the end of the day you felt humble. To me, that feeling is that these items know that they’re going home,” he said.

Legacies of colonization

Repatriation — also known as rematriation — means the return of “ancestral belongings to their community of origin to be interpreted in context by their descendants,” according to the Royal BC Museum.

Indigenous belongings were forcibly taken, sold under duress or stolen by settlers and explorers. They eventually found their way into museums around the world, with some as far away as Russia, according to a report from the First Peoples’ Cultural Council and K’yuu Enterprise Corporation.

The report found that more than 100,000 B.C. First Nations belongings and more than 2,500 ancestors are being kept at 229 colonial institutions around the world such as universities, museums and heritage sites.

The report calls on the province and federal government to acknowledge that belongings were taken by theft and duress, fund repatriation efforts both locally and internationally and support a First Nations-led organization in B.C. to carry out this work.

The provincial government is currently working to develop a policy framework for repatriation and rematriation in partnership with B.C. First Nations.

Crocker works as a specific claims researcher for Cowichan Tribes, a role that focuses on land grievances against crown governments and seeks monetary compensation for Cowichan Tribes members. He and his team work to research and prove the mismanagement of Indigenous assets or breaches of treaty obligations using historical documents like ledgers, diaries and maps.

He said the belongings in the Shawnigan Lake Museum are deeply connected to Quw’utsun land and water, and bringing them home feels like restoring a missing piece.

“It feels good to know — and for Chief Daniels to know — that our items do belong to us,” he said. “It’s magical that we were able to get them back.”

A museum for the Nation

While the Royal BC Museum recognizes that the Quw’utsun items belong to the nation, Crocker said Cowichan Tribes currently doesn’t have a space to store them without risk of degradation.

“They’re not holding it hostage or anything,” he said. “We have no place to store any of our own items. So right now, the safest thing to do is to have them left where they’re at. They’re protected.”

The Royal BC Museum has policies governing active repatriation of belongings, as well as the cooperative management of Indigenous collections and burial belongings in its care.

“The museum understands that they are our belongings, and when we ask for them back they will give them to us,” Crocker said.

He told The Discourse he would like to see a dedicated repository and museum on Quw’utsun lands built to house the belongings — a dream once held by his predecessor.

“I’m carrying on the dream of my predecessor, Dianne Hinkley. She had the same dream of doing a museum but using another space rather than creating it — but I want to go big,” he said.

Visitors can see the belongings in person at the Shawnigan Lake Museum, open Tuesday to Saturday from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m.