This is from one of our weekly Discourse newsletters. Make sure to share it and subscribe here.

Have you ever wondered where you go when you die … from a data perspective? I’ve been trying to answer this age-old existential question for the last six months. It turns out, tracking where the data goes can be as complicated as asking a Buddhist, a Catholic and an atheist to agree on what lies ahead in the great beyond.

Well, almost.

I was able to get a basic understanding of where some of your data goes when you die. For starters, provincial and territorial vital statistics offices record when people die, using information from death certificates — which include things like the deceased’s name, sex, date of death, place of death, age, place of birth and province of residence.

But if it’s an unnatural, sudden/unexpected, unexplained or unattended death, the Coroners Service is called in to investigate, which usually generates a lot more data to record.

I started tracking death counts because I’ve been trying to find the yearly totals in B.C. for on- and off-reserve fatalities. Pinning down these numbers could be important because they could point to important health and safety issues. But the numbers are hard to find.

In 2012, for instance, the B.C. Coroners Service looked into house-fire deaths including those on reserve. The report examined data from 2007 to 2011 and found people of “Aboriginal identity had 4 times the rate of residential fire death and were 20 years younger on average than non-Aboriginal victims.” Media stories have also raised questions about the lack of fire protection on reserves and access to funding for firefighting resources in small communities.

But the report didn’t tell me about other causes of death on reserve, unrelated to fires. So I asked the B.C. Coroners Service for more data, this time including all causes of death, not just fires, on and off reserve.

I was initially told the information would be difficult to round up. So in March I filed a Freedom of Information request with the B.C. Coroners Service. But I hit another wall. My request would require “a review of the coroner’s physical files,” their FOI person informed me, adding that “this data is not specifically in the database for easy extraction.”

Narrowing my request to just a few years wouldn’t help, she later told me when I called, because the on- and off-reserve information was never entered into the coroners’ database so there isn’t a way to search for it.

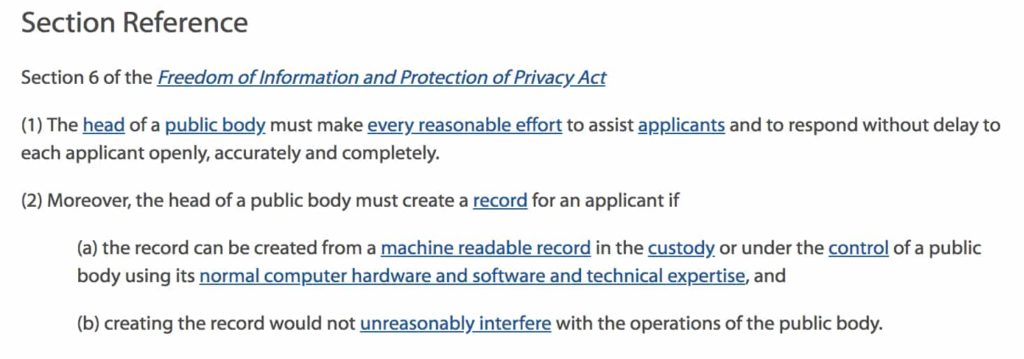

According to Section 6 of B.C.’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, a public body must make “every reasonable effort” to respond — as long as the response “can be created from a machine readable record” using the body’s regular equipment and expertise, without “unreasonably” interfering with the body’s operations.

Basically, it would take too much work for the coroners office to get this information because they would have to physically review individual files. And the team is focused right now on dealing with the opioid crisis, their media person told me.

What they were able to provide me with was a breakdown of “Aboriginal deaths” reported to the B.C. Coroners Service between 2007 and 2017. But they did not distinguish between deaths on and off reserve — which brought me no closer to understanding how many people died on reserve in those years or how they died.

I followed up again with the spokesperson for the B.C. Coroners Service, Andy Watson. He said he realizes that getting more accurate geographic information, on and off reserve, is important, and the Coroners Service is now working with federal agencies to create a more robust system. He said to check back in a few months for an update.

In the meantime, what’s next for my latest data quest?

I’m trying to see if any other organizations might have this data or if there are multiple data sets I can put together that might show this information.

Other places I’ve tried/will try:

First Nations Health Authority

Told me in an email they don’t have a mandate to collect or hold data related to deaths in British Columbia and pointed me to the coroners office.

Statistics Canada’s vital statistics unit

Told me in an email the provinces don’t supply them with anything that would allow them to determine whether a death happened on or off reserve.

I’m waiting on an open data request submitted to the B.C. provincial government.

Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation

I’ll be reaching out to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation since they filed a report in 2007 that looked at fire deaths on reserve.

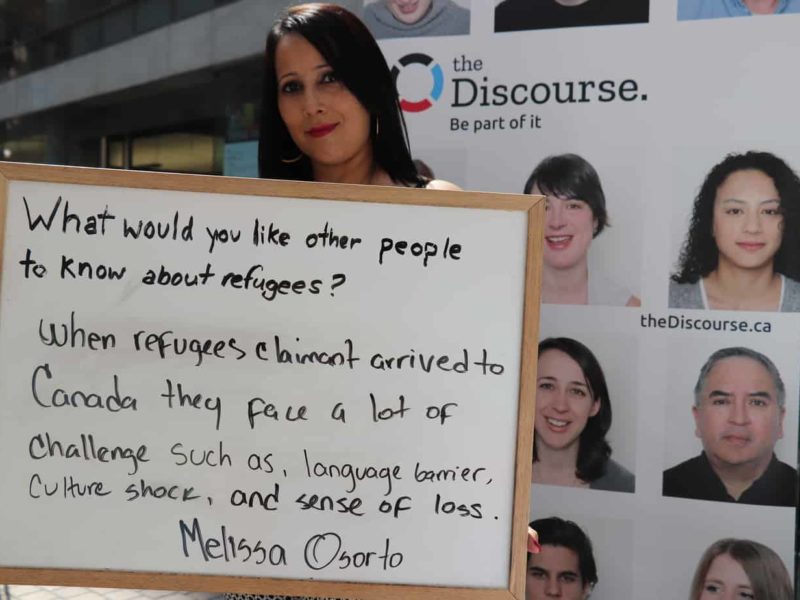

If you have any suggestions on where I should go next, or what questions I should be asking, please send me an email at francesca@thediscourse.ca

Data-hunting tips

Have you been told the information you’re looking for isn’t available because it would be too hard to compile? I talked to Trevor Presley, a senior investigator with the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for B.C., for some tips on what to do if this happens to you:

- Pick up the phone and find out why it’s a burden for the department to create this data. There is a “duty to assist” but their capacity depends on the resources they have at their disposal.

- Explore other formats. “A lot of government organizations have computer programs that are old or outdated,” says Presley. “People ask for information from them that just simply can’t be compiled in the way that it’s asked.”

- Narrow the request. For example, you might request a shorter time frame or a narrower geographic area.

- Appeal if you are not satisfied with the public body’s response to your request. Provincial and federal information and privacy commissioners exist to handle complaints related to access to information requests.[end]