Experts concerned | Universities respond | Students say they’re harmed | Help me investigate

W

hen Tamsyn Riddle was assaulted in a dorm room after a campus party in her first year at the University of Toronto, she turned to an assistant dean for help. She believed her school — Canada’s largest university — would support her. She didn’t expect to be silenced.

Instead, she alleges, the assistant dean warned her against speaking out, and told her it would be better for her if she didn’t call the police.

As she would later detail in court documents, she believed him at the time. She was 18 years old, in her second semester.

Riddle’s experience of sexual assault on campus is hardly unique. According to a 2014 Statistics Canada survey, that year 261,000 sexual assaults in this country were reported by students, amounting to 41 per cent of all such incidents. For female university students, the first six weeks of school are sometimes referred to as the “red zone,” when sexual violence is most likely to occur on campus. Yet only a small percentage of survivors on or off campus call the police; Stats Can says sexual assault is the most under-reported crime in Canada.

For two months after she was assaulted, Riddle continued to eat in the same dining hall as her alleged rapist while he faced no restrictions, and her complaint, she says, was bounced from administrator to administrator. One semester ended, a new one began, and still she felt like her concerns weren’t being taken seriously. Though some restrictions were put in place to try to keep her alleged rapist away, she says he frequently violated them without facing consequences.

When a second dean allegedly warned Riddle against sharing her concerns publicly — telling her, she says in court documents, that he had recently seen death threats against feminists on a blog and would hate to see something like that happen to her — Riddle suspected it wasn’t her wellbeing the school was most concerned about.

It’s hard to quantify how many sexual assault survivors are silenced on campuses across Canada due to policies and practices like the ones Riddle says she encountered. But one study found nine universities have restrictions, in policy or practice, on how survivors can speak about their assaults.

The study, published by a national student-led anti-violence group called OurTurn in October 2017, analyzed more than 60 sexual violence policies and student codes of conduct at post-secondary schools across Canada, and raised concerns about the harm potentially caused by silencing survivors of sexual violence.

The specifics of the restrictions vary from school to school. At Carleton University for example, students are explicitly warned that they can only talk to counsellors, support services, friends and family. At Concordia, students are encouraged to “avoid making public accusations,” such as speaking to media and sharing their experiences on social media. At Memorial, students are explicitly warned that speaking out could subject them to “discipline or other appropriate action.”

[factbox_right]

One study found these nine schools silence survivors

According to OurTurn, these nine schools have policies and practices that restrict survivors from speaking out about their experiences:

- University of Ottawa

- University of Prince Edward Island

- Carleton University

- Dalhousie University

- Concordia University

- McGill University

- Memorial University

- Ryerson University

- University of Toronto

[/factbox_right]

At Dalhousie, students are told to maintain “strict confidentiality” about their assaults, but what exactly confidentiality means in this context, and what might happen to them if they speak out, isn’t clear. (Dalhousie says it’s just a draft policy and won’t comment further until it’s passed, but hasn’t specified when it is likely to be finalized.)

And at U of T, the restrictions are not explicitly outlined in its policy, but in practice students like Riddle allege they’ve been leaned on not to speak after filing sexual assault complaints, says Jade Cooligan Pang, the vice-chair of OurTurn. U of T denies having any confidentiality restrictions in its policy.

Some universities contacted by The Discourse point to the need to protect the survivors and the accused, others to the importance of due process and privacy legislation in an employment context that would require them to protect the privacy of their employees — including those accused of wrongdoing — to explain the need for restrictions in their policies.

But such policies may be out of step with the current #MeToo movement as it creates more space for survivors to speak out, seek accountability and challenge society’s tolerance of sexual harassment and assault.

Many legal experts and student activists say the university policies go too far. They’re essentially “gag orders” censoring students, one law professor says.

These policies give universities an “unlawful and unconstitutional power,” Dawn Moore, an associate professor at Carleton University’s department of law and legal studies, tells The Discourse. “We have freedom of speech in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada, and the university is not entitled to revoke that right.”

Moore is also concerned about how vague these sweeping policies can be. If students disclose their assaults to friends or professors, it’s not clear in some cases whether they’ve violated their school’s restrictions or, more important, what the repercussions of any such violations might be.

“I have seen students be directed to take down social media posts [in] which they simply identify themselves as survivors,” she says. “I’ve seen students be told that they should not talk to the media. I’ve seen students be told that if they have talked to the university then they can’t talk to the police, and vice versa.”

Moore acknowledges that some survivors could face possible legal repercussions from their assailants if they publicly accuse them. But she says the answer is not to silence survivors but to empower them with information about their rights.

The idea that universities are looking out for their students’ best interests by silencing them is “paternalistic and assumes that somebody can’t decide for themselves what their best interests are,” she says.

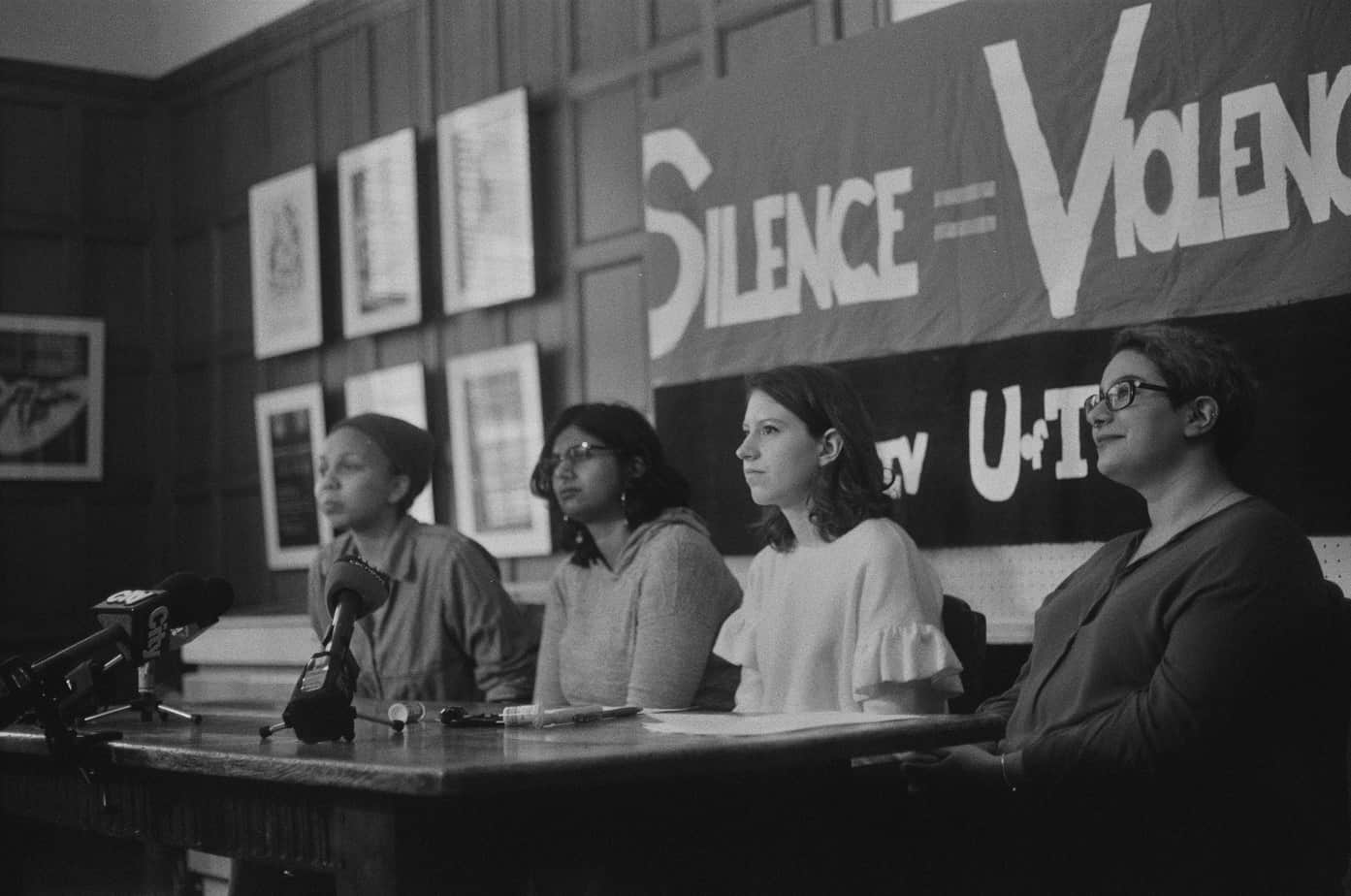

Seventeen months after Riddle was assaulted and sought help from her school, U of T closed her complaint without any real resolution, she tells The Discourse. Outraged, she applied to file a human rights complaint and held a press conference in April 2017, alleging the university mishandled her case and failed to provide her with a safe, discrimination-free learning environment.

In its statement of defence filed with the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal on Aug. 18, 2017, the university denied Riddle’s allegations and said administrators took her complaint seriously, investigated it promptly, and are committed to providing a safe, healthy and supportive environment for its students. A mediation session was held in December 2017, Riddle says, though she won’t yet elaborate on its outcome.

While Riddle went public with her objections to the way her school handled her complaint, she worries that policies and administrators like the ones she encountered are scaring other survivors into silence.

“I think for someone else, it could have easily made them feel more silenced,” she says.

Top

Legal experts say ‘gag orders’ go too far

Karen Busby, a professor in the University of Manitoba’s law faculty, studied 22 sexual violence policies across Canadian campuses in February 2017 and found that privacy laws play a key role in what employers can reveal.

Employers are restricted from disclosing any allegations made against their staff, she explains. And workplace health and safety regulations also limit what employers can reveal — or even that a member of the workplace has been named in a complaint. “So there’s privacy laws that kick in and constrain what can be said,” she says.

Still, she was surprised to see how far the restrictions go in the 22 policies she examined.

“Almost every single one of them have some kind of gag order in them,” she says. “So they prohibit sharing before the investigation, after the investigation — some prohibit sharing anything such as the fact of an investigation, the names, the details, the findings, the summaries, the sanctions.”

While some of the policies allow “for a little bit of disclosure of a few things here and there,” she says, “for the most part they’re extremely prohibitory and don’t allow complainants to speak with anyone, really, other than professional counsellors or advocates.”

Even if an accused person is found to have violated a school’s sexual misconduct policy, it’s still not clear from these policies whether they can be named, she notes. “I find that really interesting.”

“These confidentiality orders go far beyond what privacy legislation would require,” agrees Pamela Cross, the legal director of Luke’s Place, a resource centre that provides legal support for women and children experiencing violence in Ontario, as well as specialized training for lawyers and support workers.

And these policies “have a way of silencing women’s voices, silencing women from being able to talk about the experiences that so many of us have had with sexual violence,” she adds.

She calls the gag orders “awful” and “disgusting,” and says they’re designed to protect the universities’ reputations rather than survivors.

In a culture that has yet to consistently support survivors, Cross says universities are not alone in silencing survivors’ voices.

“We really don’t want to hear of women’s experiences of sexual violence that they’ve been subjected to,” she says, “because then we have to become horrified by how extensive it is, how entrenched it is, and how little we’ve done over time to address it.”

Top

They’re not ‘gag orders,’ universities say

The Discourse contacted all nine universities named in the OurTurn study to ask them about their confidentiality restrictions.

Concordia denies that its confidentiality requirement amounts to a “gag order.” “It is not intended to silence survivors,” spokesperson Mary-Jo Barr tells The Discourse in an email, “and there is no obligation on the survivor to keep the situation confidential.”

Rather, Barr says the section — which urges survivors to “avoid making public accusations” — is intended to “remind members of the community of how damaging it can be to publicly ridicule, shame or criticize someone who is the object of allegations.”

Like Concordia, the University of Prince Edward Island says the confidentiality clause in its policy does not restrict survivors from speaking out. Instead, a spokesperson tells The Discourse via email, it’s intended to “help protect the confidentiality of the survivor from being breached by other members of the University community.”

UPEI says it’s in the process of creating a new standalone sexual violence policy in partnership with the school’s student union, which is expected to be approved later this year. The university “takes the safety and security of the entire campus community very seriously,” the spokesperson adds.

Steven Reid, a spokesperson for Carleton, says the university “values the voices and experiences of survivors.” The policy’s confidentiality clause, he says, “is not to silence survivors but to ensure the integrity of the investigation” and to ensure that both parties get due process.

Reid also says the confidentiality clause ceases to restrict survivors after their cases are closed. Once the process is complete, he says, “both parties are free to make public statements as they wish.”

Though Carleton’s policy explicitly restricts public statements “while a formal complaint process is underway,” The Discourse found that it does not clarify that the confidentiality requirement lifts when a case concludes.

Like Carleton, Ryerson emphasizes that confidentiality is required to ensure “procedural fairness” and “preserve and maintain the integrity of the investigation so the findings can stand up to scrutiny.”

Ryerson also mentions the need to respect privacy legislation, as does the University of Ottawa, which says its policy covers both students and employees in an employment context, and is therefore subject to the Occupational Health and Safety Act. So how much confidentiality is required depends on the role of each person named in the complaint (whether the accused and the survivor are students or employees, or both), “the relationship between the person receiving the information and the person reporting it, and the content of the information provided,” a spokesperson for the University of Ottawa told The Discourse by email.

McGill and Memorial did not respond to questions by deadline.

Policies undermine healing, students say

Caitlin Salvino worries that an unforeseen consequence of the schools’ restrictions is they’re preventing survivors from healing.

Before finishing her undergraduate degree at Carleton in 2016, Salvino challenged the draft version of her university’s sexual violence policy, and mobilized a group of students to write an open letter in protest.

The school only gave students a few weeks to weigh in on the policy via email, she tells The Discourse, and the draft did not specify whether survivors would ever see the results of their investigations.

Carleton’s Steven Reid says students had three weeks to send feedback on the draft, which was written after more than 30 meetings and consultations with students and union groups as well as anonymous feedback online. More than 140 individuals and groups weighed in on the draft, he adds, including an “open letter” received from “the Carleton community.”

But the draft didn’t focus on the needs of survivors, Salvino maintains, and may have deterred them from reporting at all.

Though Salvino acknowledges that Carleton made a few changes to the policy before passing it, she says they didn’t go far enough. The students’ protest continued and coalesced into a national group called OurTurn, which has now heard from survivors across the country.

When student survivors openly share their stories with the group, they’re sometimes taking “a very real risk,” given the restrictive policies some of their schools impose, Salvino says. But it’s a risk these students are willing to take in order to find support, she adds.

For the survivors who have contacted OurTurn, Salvino says, “a key part of their healing process was speaking openly about what they experienced and also finding a community, and getting involved in activism.”

If the goal of the schools’ sexual violence policies is to address rape culture on campus (as Ontario, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Quebec schools have been ordered to do by law), they’re falling short, says Carleton professor Dawn Moore.

If policies are supposed to prioritize, rather than silence, concerns about violence, listening to the voices of survivors should be essential, she continues.

“Speaking the name of an accused person — that’s not something I would necessarily advocate for,” she says. “But being able to self-identify as somebody who has been assaulted is core to a lot of subsets of the survivor community, and is one of the guiding principles.”

While universities may not be deliberately trying to harm survivors, the effect of these policies is nonetheless extremely damaging, says Mandi Gray, an activist and post-doctoral student at York University.

“It might really seem like [universities] do have the survivor’s best interests at heart,” Gray says. “I think that’s what I so often hear and that’s probably the most heartbreaking thing — that we take all these promises of, ‘It’s going to be resolved, just sign this confidentiality agreement and we’ll investigate.’ It keeps [students] silent and then we’re just stuck waiting and waiting and waiting.”

Empowerment through independent advice

Silencing survivors with sweeping gag orders will only sustain the status quo of a society that tolerates sexual violence, Pamela Cross says.

But arming survivors with the information and support they need to speak out safely will help them make better choices to empower themselves, she says.

Cross is part of an Ontario pilot project that offers free legal advice to survivors of sexual assault in Toronto, Ottawa and Thunder Bay. She and other lawyers specializing in sexual violence offer survivors up to four hours of independent advice to help them evaluate their next steps and figure out what they can and can’t say publicly.

Cross believes this model should be implemented across the country, and says it can be particularly beneficial for student survivors so they can share their experiences and know their rights — and not depend on large institutions with their own interests to guide them.

“The survivor’s interests and the university’s interests, by definition, are in conflict with one another,” she explains. Survivors are looking for support and possibly compensation — or at least some acknowledgement of what they’ve experienced — while universities are looking to minimize damage to their own images, she says.

That’s why students deserve advice from people other than university administrators on how to proceed when they’ve been sexually assaulted, she says.

She’s particularly concerned about younger people who turn to their schools for protection and support, then feel pressured to agree to remain silent, without fully understanding the long-term implications.

“If you think of it from the perspective of a student, maybe 19 or 20 years old, who’s already traumatized by the sexual assault, who’s embarrassed by it, who may feel a certain sense of shame — all of those things that we know go along with virtually every sexual assault — [who] reports to the university because she expects that institution will protect her, and she’s told, ‘We could do this or that for you but you have to sign this first…’ It’s understandable, at the time, that some of those women would sign the paper,” she says.

Back at the University of Toronto, Tamsyn Riddle suggests similar remedies. Survivors need support from unbiased, independent counsellors and investigators who understand sexual assault and aren’t employed by the universities, she says.

For Cross, removing the gag orders is a necessary first step to change.

“We silence the voice, we silence the story. And that woman doesn’t get to tell her story — maybe that makes it less likely that the next woman will come forward with hers because that next woman is sitting there thinking, ‘Well, I’ve never read anything like this happening at my campus. It must be me, it must be a problem with me,’” she says.

But survivors aren’t the problem, she says. “There are so many ways that women are silenced.” [end]

[cta]

Have you been sexually assaulted and silenced on a Canadian campus?

Help us document the impact of “gag orders” on Canada’s campuses. Click here for our survey.

[/cta]

This piece was edited by Robin Perelle with fact-checking and copy editing by Jonathan von Ofenheim. The Discourse’s executive editor is Rachel Nixon.