When Alethea Stanford received a package from her landlord in the mail on April 6, she says at first she was just confused.

Reading over the significant stack of documents inside, there was one thing that was clear: her new landlord intended to raise rents in their apartment complex.

The rental hike was to recover costs for renovations and repairs the previous landlord had made to the buildings over the last couple of years, including replacing the plumbing and putting on a new roof.

Stanford lives in a three-building, five-acre complex at 501 Sixth St. called Willow Grove Estates. It was built in 1982 and was acquired in November 2022 by Headwater Projects, a Vancouver-based real estate investment firm.

According to Stanford’s documents, on Feb. 27 Headwater’s asset manager Morgan Kofoed made an application to the Residential Tenancy Branch (RTB) to have at least some of these costs — called “capital expenditures” — covered by an additional rent increase that goes above and beyond the two per cent that is currently permitted.

They were looking at permanent rent increases in the range of $17 and $143 per month, depending on the building, with higher amounts stretched out over three years. With most renters paying about $1,000 a month, Stanford worried that the additional cost could push some tenants out, and options in the current rental market are slim.

On a limited income, Stanford was scared. The first thing she did was run downstairs to talk to her neighbour. There are a lot of vulnerable tenants in her building — seniors, people with disabilities, folks on fixed incomes, she says.

“She was like, ‘I don’t even understand this package and what this means.’ So I just thought, okay, well, I’m gonna go through it,” says Stanford.

“When I went through everything, all these capital expenditures … I was sort of like, wow, this is just so confusing. And this is definitely not right.”

The next thing Stanford did was draft a letter to all the other residents in her building, explaining what the charges were.

Here’s what she came to understand.

What is an additional rent increase for capital expenditures?

In 2018, the province of B.C. decided to change the way it calculated rent increases, capping it to the rate of inflation only. Before that point, it was tied to the rate of inflation, plus an extra two per cent, a formula that was set in 2004.

The changes were a result of recommendations from B.C.’s Rental Housing Task Force, which received feedback that not only were the rent increases unaffordable, but that tenants were being subject to the maximum increases despite building maintenance going uncompleted, a spokesperson for the ministry of housing told The Discourse, via email.

“Our new approach strikes a balance between giving relief to renters while encouraging people to maintain their rental properties,” stated premier John Horgan at the time. The province also said in 2018 that they intended to “work closely with landlord advocacy groups” to find ways they could apply for additional rent increases to offset their costs.

The result was new residential tenancy changes enacted on July 1, 2021 which allow for an additional rent increase, but for capital expenditures only — maintenance expenses like painting are not eligible.

“Rather than the additional two per cent applying to all annual rent increases, the [new] process allows landlords to increase rent by a modest amount only when they have completed necessary maintenance on the rental property,” stated a ministry of housing spokesperson, via email.

Now, once the landlord pays for the capital expenditure — like a new roof or windows — they then apply to the RTB to recoup their costs from tenants via a requested additional rent increase. The RTB then schedules a hearing with all parties.

The tenants have no recourse to oppose the additional rent increase, other than to make a case either that the work was only necessary because of neglect or inadequate building maintenance, that the landlord was already compensated by a different source, or that the increase is for routine repairs and maintenance, which are not permitted.

General maintenance and upkeep of the building are excluded items in the additional rent increase expenditures because they “are considered to be routine costs that landlords are typically responsible for,” a ministry of housing spokesperson told The Discourse, via email. This is why eligible costs are limited to capital upgrades of major systems and components — because those “are costly to replace.”

Calculating the additional rent increase uses a somewhat complicated formula. Landlords take their eligible expenses, like a new roof or windows, divide it by every unit in the building, and then divide that by a ten year (or 120 month) amortization period.

If the resulting monthly amount is more than three per cent of a tenant’s rent, then it is capped at a maximum three per cent increase. This increase is then spread out over three years or “phases.”

This three per cent increase is in addition to the yearly increase tied to inflation (currently two per cent), and it can be “stacked,” meaning each year it is recalculated and the additional amount added on again. So the total rent increase for the tenant can go as high as 15 per cent over three years, depending on inflation and how much the landlord is claiming.

Crucially, after the three-year limit, the rent increase remains and is not reversed. Though this reform was modelled on similar legislation in provinces like Ontario, there the additional rent increase is later removed at a set date, based on the lifespan of the expenditure.

At Willow Grove, the packages sent out to tenants outline different rent increases based on the varying levels of repairs and renovations on each building.

For the residents at Stanford’s home in building A, the requested increase per unit is $57.04. In building B, where there weren’t many expenses — new hot water tanks and some lighting and electrical panel replacements — the increase is $17.01.

However in building C, where expenditures included larger items like a new plumbing system, new carpets and a new roof, the requested increase is $143.06.

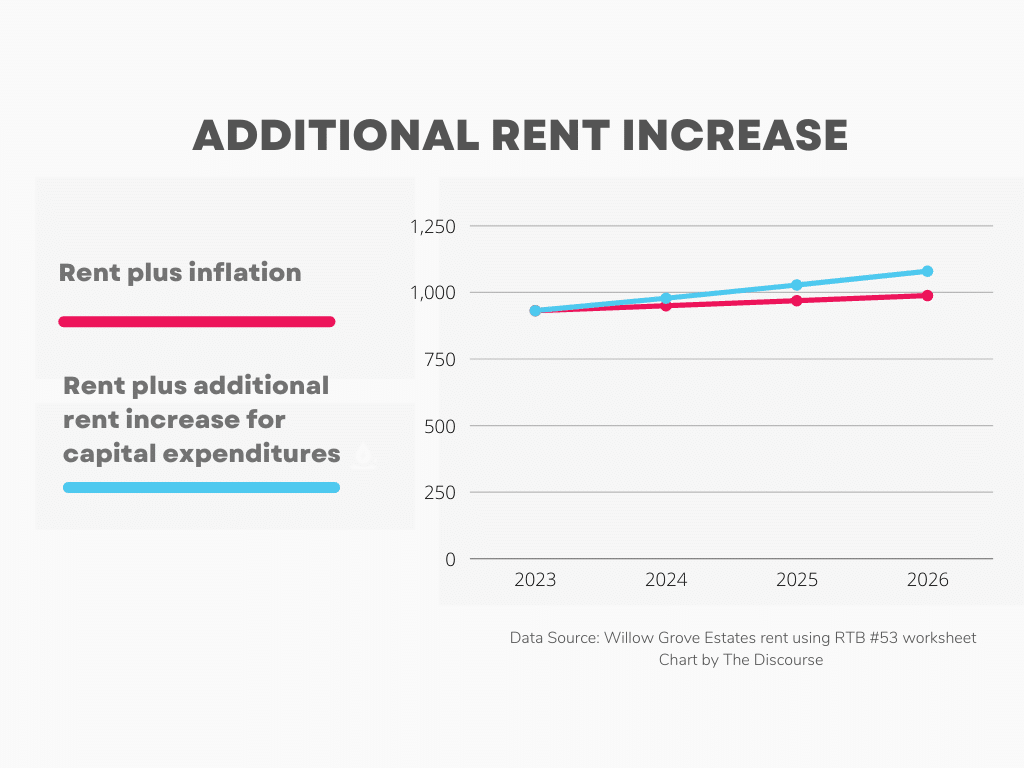

In building C, a tenant told The Discourse their rent is currently $931 per month, for a one-bedroom apartment.

To calculate their likely rent increase, we’ll assume the RTB grants the landlord their full request of $143.06, and that the inflationary rent increase just stays at the current two per cent (though in reality it may fluctuate).

The tenant’s increase would first include the allowable provincial amount of two per cent, after which the landlord’s additional three per cent is added, to raise next year’s rent to $978.11.

For the following year, if the rent increases again by two per cent for inflation and then another three per cent for capital expenditures, the tenant’s total rent for 2025 would then be $1027.60 per month.

The third year’s rent, when calculated this way again, ends up being $1079.59. At this point the three per cent increase ends, unless the landlord has made new eligible expenditures and starts the process over for another increase, which is allowed. But the rent increase stays at this amount and does not go back down.

At this point the capital expenditure increases plus the allowable amount for inflation means the total amount the tenant pays has gone up by $148.59 per month, which represents a roughly 16 per cent increase in their rent.

‘This is how market rental housing works’

So in broad terms, what does this all mean?

As Robert Patterson, lawyer at the Vancouver-based Tenant Resource and Advisory Centre (TRAC), summarizes it: “This is just another way for those with more capital, and landowners, to get those with less to subsidize the cost of maintaining and upgrading their assets.”

This shift in financial responsibility for the upkeep of properties onto renters instead of solely on owners bothers Stanford as well.

“Why do we have to pay for it? Tenants don’t own houses. We don’t own our units, but we’re having to pay for the cost of maintaining [a] building that isn’t even ours,” she says.

The Discourse put this question to David Hutniak, CEO of Landlord B.C., who says he led much of the conversation regarding additional rent increases with the RTB.

“That’s not a true statement. They get the direct advantage of that. First of all, the [additional rent increase] represents a fraction of the cost of many of these investments,” he says.

In the case of Willow Grove, for example, the landlord calculated they needed an increase of $143.06 per tenant to cover the capital expenditures for building C, but the three per cent increase cap means that over the three-year period, they would recover roughly $89.86 in extra rent — so not the full amount. However the rent increase is permanent, so it could be argued that those expenses will eventually be recovered.

Though not unsympathetic to renters and the challenges they’re facing, Hutniak says those challenges need to be balanced with ensuring that landlords continue to stay in the business of providing rental housing during a supply crisis.

“People want housing, we get that. But housing requires constant investment. That has to be paid for somehow,” he adds.

A question raised by tenant Arbie Fru, which was also put to Hutniak, was — aren’t those capital investments eventually recouped by the landlord (and then some) when it comes to the sale of the building?

“Anybody who’s doing a roof is not doing it because it’s going to increase the value of their property, they’re doing it because they have a leaky roof. And if they don’t fix that, and make that $100,000 investment, they’re going to have a multimillion-dollar cost,” says Hutniak.

“That’s the nature of being a tenant, whether it’s a commercial tenant or residential tenant, what-have-you. That’s part of the contract. And if people feel it’s unfair, I don’t know how to respond to that other than, you enter into a contract to rent one’s home, to rent your home with that understanding. And this is how market rental housing works.”

At TRAC, big-picture questions aren’t the only thing that advocates like Patterson grapple with.

The regulation states that the capital expenditures are to replace or repair a major component or a major system, but “the definitions of those are so slippery,” he says. TRAC saw one case in which additional rent increases were approved for an amenity room, even though none of the tenants whose rents were raised to pay for it had guaranteed access. In another case, one landlord claimed the resurfacing of parking lots, and all tenants were charged — even those who didn’t even have the right to park there.

“So effectively, there’s very few rules. Landlords are kind of trying all kinds of stuff, and are succeeding, even sometimes when they’re providing very little evidence,” he says.

Tenants at Willow Grove have their own questions about what expenses are permitted.

According to documents provided to The Discourse by Fru, the landlord hired Vancouver-based company BMS Plumbing & Mechanical to complete work on the plumbing system in building C.

Accommodation, meals, and transportation for their workers was included within the 2021 pricing quotes, and BMS estimated the project would take 1.5 to two months to complete.

“Don’t we have a plumbing company in town?” says Fru. “I don’t think that food and accommodation counts as a capital cost.” A representative from BMS did not respond to a request from The Discourse for clarification on the charges.

Fru also expressed concern that allowing these rent increases would have the effect of discouraging regular maintenance of buildings because those costs are not eligible.

“This legislation does not encourage maintenance. It encourages ‘put a roof on it and ignore it for ten years,’ until it’s deemed that the lifespan’s over, and then do another one and charge us for it,” he says. “Don’t go out and get the carpets cleaned every year. Let the dirt grind in for ten years and then replace them.”

Though it’s true that cosmetic work such as painting cannot be included in capital expenditures, the rules around it are somewhat contradictory, says Patterson. For example, if a landlord upgraded their building’s floors and in the course of that repair changed the flooring from linoleum to marble, they could theoretically add the cost of marble flooring to the project and then pass that on to renters, he says.

Another issue is that there’s no minimum requirement when it comes to other categories of eligible capital expenditures, like those that reduce energy use or greenhouse gas emissions in a building, Patterson says. This means that even “something that decreases the electrical consumption of the building by, I don’t know, one-megawatt hour would be enough.”

Problems exist with the new residential tenancy changes for landlords, too.

All additional rent increases have to be approved by a dedicated RTB arbitrator, something Hutniak describes as a “robust, time-consuming process,” though that seems to be slowly improving.

Because of this, he believes “the vast majority of landlords will never take advantage of the additional rent increase process, because it’s complicated and oftentimes, the rent recovery — if you were making a claim that’s nominal — it’s just not worth the hassle.”

One thing that Hutniak, Stanford and Fru all agree on is that the two per cent increase on top of inflation seemed like a better and simpler system.

“You ask any landlord — and any landlord who is in a position, resource-wise, to go through this onerous process — they would relish going back to the two per cent plus [inflation], to a simple formula,” says Hutniak.

“There are better ways to incentivize maintenance that do not transfer costs on to tenants and that do not gift landlords with increased profits,” writes Dianne Varga, a Nanaimo-based renter’s advocate and policy analyst whose building is also currently challenging to a similar rent increase.

One solution could be for government to enforce appropriate property standards and “impose penalties on landlords when certain necessary repairs are not completed” rather than bring in measures that cause harm to tenants, she says.

As a matter of course, when a landlord applies for an additional rent increase to cover capital expenditures, the RTB schedules a hearing between the landlord and tenants to discuss the matter. Willow Grove’s is set for July 10.

At the urging of other tenants, Stanford has agreed to serve as their representative at this hearing.

“The rent increase mechanism is outlined by the Residential Tenancy Branch. We have no further comment beyond that,” said Richard M. Anderson, president of the complex’s Vancouver-based management company Hunter McLeod, via email.

When reached by phone, Willow Grove’s building manager Gerald Bam said he would be unable to comment until after the proceeding with the RTB. Representatives from owner Headwater Projects did not respond to interview requests.

After initially drafting a letter to all the tenants, Stanford hosted a meeting with the residents in building A on April 15. Two weeks later, she organized a larger gathering for the entire complex on April 29 in the complex’s grassy outdoor commons area, which was attended by about 50 residents.

Fru has worked as a property manager at various buildings, including Willow Grove, and says he immediately got involved because the whole thing “didn’t seem right.”

He struggles with the concept that landlords should retrieve their costs from tenants “without having to actually do anything, like properly manage your money,” he says. “You bring in the rent, you pay the electricity, you pay the taxes and whatever, and you get this much left over and you put it aside … and that’s for repairs and maintenance.”

If landlords expect tenants to pay for capital expenditures, then they should share the eventual profits with those tenants when they sell the building, he adds.

Even though his own $17 potential rent increase in building B is relatively small, he’s certain his building will also soon need major work.

“I can’t see this [building] being that far behind. If they do the roof, they’ll hit us again,” he says.

By now, Stanford estimates that about half of the complex’s total 147 apartments — or approximately 70 people — have now joined the effort to resist these rent increases, and many attended the last all-building meeting on June 4.

“My main focus is just doing the best I can for everybody,” says Stanford, on the reason she has devoted so much of her time to this cause. “I think I put a lot of pressure on myself that way, but that’s just my main priority.”