This story contains details of abuse at residential “schools.” Please read with care. Support for Indigenous survivors and their families is available. The KUU-US Crisis Line Society offers 24-7 support at 250-723-4050 for adults, 250-723-2040 for youth, or toll free at 1-800-588-8717.

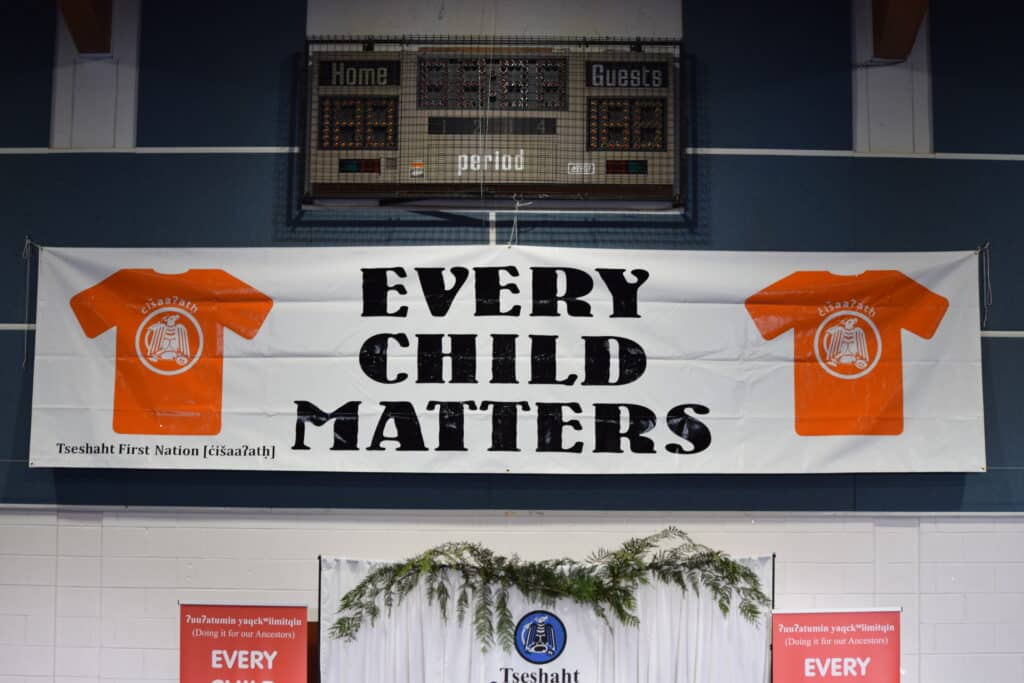

On Tuesday, c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht) First Nation announced their findings from the ground-penetrating radar examination of the site of the former Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS).

The “school” operated from 1900 to 1973. I attended from the age of five until I was 14: 1956 to 1964.

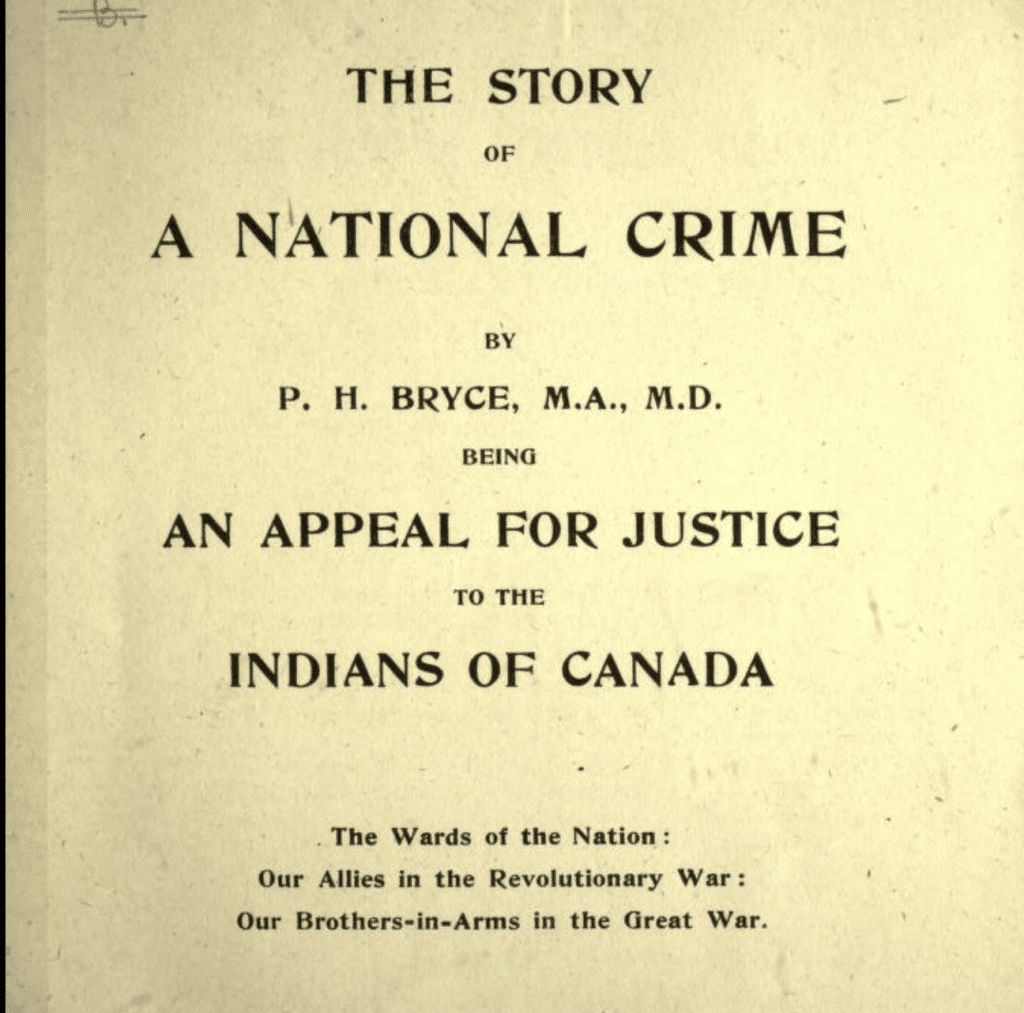

Back in 1922, the chief medical officer of the federal Departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs, Dr. Peter Bryce, presented an official report to the Government of Canada stating clearly that the government had to do something about the large number of deaths in the 31 “schools” he visited.

In one institution, File Hills, Dr. Bryce found nearly 70 per cent of the children had died.

He fought the remaining years of his life to have the government do something but they refused. Dr. Bryce’s report is available online.

A good source for commentary is Defining Moments: Bryce@100, an online curriculum and resource project that documents Dr. Bryce’s legacy 100 years after the National Crime report was published.

On Sept. 30, 2022, Celia Haig-Brown, Gary Gottfriedson and I launched our book, Tsqelmucwílc: Kamloops Indian Residential School, Resistance and A Reckoning, on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

This was one year after Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc announced it had found evidence indicating 215 unmarked graves. The title of this book means “becoming human again” in Secwepemctsin.

It was a reissue of Resistance & Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School, which I published in 1988. Nobody wanted to hear about or talk about sexual abuse or Indian residential schools in the 1980s. So, it is gratifying to see so much attention being paid.

I was the accountant for the West Coast District Council of Chiefs in Port Alberni when we shut down AIRS and moved the tribal council offices into the former school. This brought a great sense of gratification.

The numbers reported by c̓išaaʔatḥ on Tuesday were extremely sad: 17 possible unmarked graves were discovered. 67 students were found to have not returned home according to records.

During my time in the “school” we were fully aware of one student disappearing and never being heard from again.

My late uncle, Dr. George Clutesi, was a maintenance man in AIRS. He told me and my wife about being ordered by the principal to clean out the barn. He said there was so much blood and flesh in the barn he was certain the student who was whipped could not have survived.

Students attended the school from all along the coast of B.C., all the way from Stewart to Victoria. This is just the beginning of a long process that will likely involve many nations.

The government and the churches who operated the schools need to increase funding and programs for survivors and their families. Many of the social problems within First Nations communities result from these institutions.

Much more effective addictions treatment is needed for First Nations youth. They are our future!

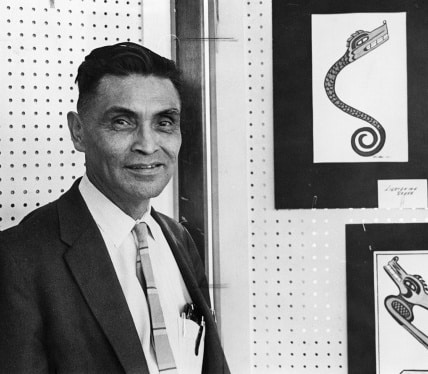

Randy Fred is a Nuu-Chah-Nulth Elder and writer. He has spent his life working in different media, from radio to books to magazines. He is the founder of Theytus Books, the first Indigenous-owned and operated book publishing house in Canada. He lives in Nanaimo, Snuneymuxw territory.