The pregnancy with my first child was unexpected. I was 26 years old, just returned from traveling in Europe. It wasn’t really in the cards, until it was.

I can’t remember how well I knew Craig Evans at that time, I think I had met him during a workshop at the local youth program I had been a part of. He taught us about local farms and food security, talking about how everyone had the right to cheap and abundant quality food, with a passion that saturated everyone around him.

Craig was one of the first people that I told about the pregnancy, as he stood behind a vendor table at the local Seedy Sunday event. I was scared, and staying at my mom’s house, in the old bedroom I’d had as a teen.

At this time Craig was the garden supervisor at a therapeutic farm in Duncan, the next town over. I told him of my uncertainties, that I felt lost. In reality I was trying not to panic, pushing back against the sense that I was stuck in an undertow, receding backwards, locked into a timeline I couldn’t control.

There was a program I could access through the local job centre, I told him, one for “troubled youth,” I said with a laugh. They’d pay for a course if it would help me to become employed, and they’d also pay me an hourly wage while I studied, for up to three months. Maybe that was something I could do until the baby came.

Craig looked at me for a long moment, and then he spoke. The farm he worked at was registered as a post-secondary education facility, he said. We’d design a course just for me, one that fell just under the three month mark. I could work on the farm and learn horticultural therapy, and even get a certificate at the end. “It’s perfect,” he said with a grin.

For the next 12 weeks, every weekday morning, Craig drove across town to my mom’s house at 5:30 a.m. to take us both to the Duncan farm.

Most of the 45-minute drive was taken up with talking about the pregnancy, how wonderful the baby would be and how much fun I’d have. He talked about his own child, named Robin after his childhood hero, Robin Hood.

Some days he’d just talk in broad strokes about his vision for food security, which was simple: “Grow as much food as possible and make it available at a subsidized rate to people who are in need.”

For him, growing was healing — for himself and others.

Every day at the farm he made sure I ate lunch, was protected from the sun, drank enough water and orange juice, and had tissues for my allergies. If I was tired he’d send me upstairs to rest in the farmhouse.

Eventually I got too large and round to bend over and pull weeds, so some days he’d send me to sit in the greenhouse and pick baby lettuce leaves or transplant red peppers into one-gallon pots and chat with the other participants.

Most of the folks working there lived with various challenges ranging from blindness to schizophrenia to Down syndrome, but the way Craig ran the farm, he spoke to and treated everyone equally. The way we were all mixed together, it was often hard to tell who was a participant and who was an employee. At the end of every day, he’d pile my arms with flats of tomato starts and sunflower seedlings and deliver me home again.

One morning, driving to the farm, we saw a figure slumped along the highway meridian, as though sleeping.

“A bear,” Craig breathed. We could hardly believe it.

He pulled a U-turn and went back. Parked, we approached with silent reverence. It was young, with glossy black fur and huge feet tipped with shining claws. He gingerly lifted a paw and studied it.

“It has fingerprints,” he said quietly.

The month before I gave birth, Craig was headed out for one of the many multi-day hiking trips he went on and asked me to house-sit and look after his ancient cat, Poo Kitty. He lived in a rickety old character home downtown, perched at the top of a hill that overlooked the ocean.

Just prior to his departure, Craig regaled me with stories of Poo Kitty: what a matriarch, how regal, how long-serving, how good.

A couple days after he left, the doorbell rang and I opened it to find the neighbour standing there, distraught and holding a garbage bag. She tearfully handed it to me, with a note.

When Craig returned, I told him about how I had attempted to tidy and organize the house while he was gone, noting that, as he seemed to like to collect things, lots of things (maybe even things that some might view as trash), I left some items where they were and tidied around them.

“Like, for example, I’m not sure what this is.” I picked up a hardened shriveled husk from the windowsill and held it out.

A grin played at the edges of his mouth.

“That is the carrot I put in Robin’s lunch box on the first day of school.” Robin was now a teenager.

“Craig! No!” I shrieked.

“Let me show you something else,” he said, and ran to the basement, returning with a mason jar, which he held up. It contained a few dried daisies. “Do you know what these are?” he said. I shook my head. “These are the first daisies that bloomed the summer after Chernobyl.”

“Oh that is lovely,” I laughed. “But you’re crazy.”

“I didn’t know what would happen. Julie, I didn’t know If we’d ever see daisies again. It might have been the last summer that we’d ever see daisies.”

When he asked about Poo Kitty, I told him I had some bad news and handed him the note.

He read it silently and then looked at me for a moment.

“This might be the best possible outcome,” he said slowly. I looked confused.

She had lived such a good long life, and though gruesome, her death was swift, he said. She didn’t suffer. He put a hand on my shoulder and reassured me it was okay.

At that moment it struck me that Craig really thought like this, that he truly possessed some perspective that allowed the beauty in life to consistently shine out at him, even in darkness.

This perspective never wavered, and it was the same this July — 18 years later — when he called to tell me he was dying.

“A couple of months ago they said I had three to six months. It’s just a progressive cancer that they’re not going to be able to contain or control. Unless you believe in miracles,” he said with a chuckle. The cancer was so advanced that all they offered him was palliative care. He paused while I registered the shock, and then continued. “But when you think about it, I’ve really had a lot of fun. I don’t know anyone else who’s had as much fun or was able to do as much stuff as I have.”

“Of course you would be positive,” I said through tears.

“You know, for years, I have always told my partner, ‘I think there’s something wrong. I am overly optimistic. I am so overly optimistic, I think I should be medicated. I think there’s something… why is everything so wonderful?’ And that hasn’t changed. Everything is so unbelievably wonderful. We all pass. It’s been such a privilege to have life,” he said.

The tears would come again and again, out of nowhere — in a parking lot, in the bathroom, in a store aisle. I came to realize that, in a way, I wasn’t even crying for him, not really. He seemed to approach death with the same quiet acceptance, courage and buoyant enthusiasm that had embodied every day of his life.

I was devastated for the rest of us, who had to face the prospect of a world without him.

The blue hole

Over the weeks and months that followed, I visited Craig at his home and at the Cline Agri-Health Centre, where he and his life partner Jen Cody run a non-profit farming cooperative called Growing Opportunities, which — along with their Five Acres Farm location in Harewood — supplies training for employees with diverse abilities and provides thousands of pounds of fruits and vegetables for Nanaimo Foodshare Society’s affordable food boxes and for local farmer’s markets.

It’s their fourth year on the site, though Craig has been at the forefront of the local food security movement for decades, from his founding of Nanaimo Community Gardens in 1987, to the creation of the Nanaimo Foodshare Society the following decade, to his roles as the former market garden manager at Providence Farm and as a worksite trainer with Vancouver Island University for their employment and life skills training program.

“The goal of agriculture is to create permanent grazing fields for people that we can just open the gate, walk into and there’s lots of food there at all different times of year that we can harvest,” he said one afternoon at the farm, as he shook kale seeds off of dried stalks into a garbage can.

“That’s the beauty of saving your own seed, planting it out, looking at how it grows — what diversity there is — and then choosing what you think might work well in a perennial food system that takes the least amount of work to maintain.”

Following his diagnosis, Craig said there was little else he would rather be doing than to carry on with his mornings at the farm, so I hung out with him there as he hauled boulders, weeded, picked heirloom tomatoes, blue-green cabbage, purple sprouting broccoli, lemon cucumbers and patty pan squash. He took breaks when needed and napped in the afternoons.

“When I work out here, I have no issues with my health. It’s no aches and pains, no, ‘Oh god, someone’s kicked me in the gut.’ But if I stop and go home and sort papers…” he said with a laugh. Hiking also helped to stave off his nausea. On one of my visits we walked the rows together, and Craig pointed to the birds dipping in and out of a barn on the property.

“Barn swallows. There’s a stage where all the young ones are like, ‘We can fly, we can fly!’ And they have a very particular song. So when they start flying, the adults fly and then the young ones are flying, you can hear the, ‘I can fuckin’ fly, I can fuckin’ fly!’ You can hear them call that out, and it’s beautiful,” he said with a chuckle.

As we watched the birds, I asked Craig how he seemed to have reached such a sense of peace with the fact that his illness is terminal.

“[It] came for me at an early age, realizing that my existence is like a firefly. It’s just going to be — burst — and it’ll go out. So I wanted to really make sure it was, ‘How many summers do I have? How many? How long do you get?’ I really wanted to make sure every summer really counted. For today, this is my last summer, and did I ever bank it,” he said with a grin.

“I booked summers all along that were full of joy, full of fulfillment, full of purpose. I’m comfortable. I’m so comfortable … No matter what, there’s a finality to everything. Everything in the garden has its season.”

Craig’s final summer was one for the history books, lingering almost implausibly long and hot well into the end of October.

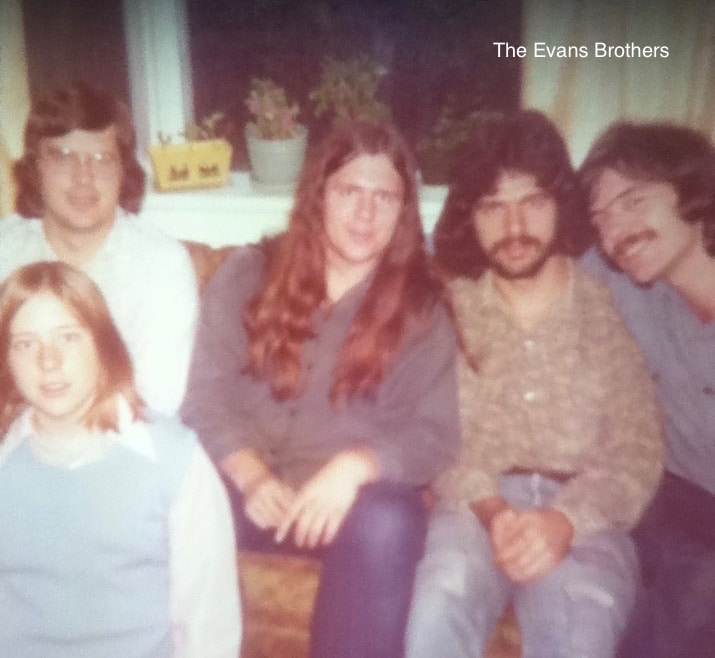

Growing up on a cattle ranch in Ontario, Craig said he became a “closet vegetarian” at 13, after watching how the cows interacted on the farm.

“I saw that the mom cattle loved their babies,” he said.

Earlier on in the summer he returned to that childhood farm on a road trip with Jen. The woman who now lived there welcomed him like family, he said, thrilled that one of the five “Evans boys” had made a return.

It was idyllic, visiting old family and friends — many of whom he was surprised to see had given up their lives in the city and started farming themselves — and returning to places he had first explored as a teen.

“We went to a place in the Bruce Peninsula, the Cyprus Lake park. We’d always go there and do acid on the cliffs. I have eight-millimetre film footage of my friends and I showing it on our tongue and swallowing it. We’re on the cliffs. It’s like, dreamy footage. Dream footage. And in this place there was what’s called The Grotto. We used to call it The Blue Hole,” he recalled.

The Grotto was a limestone cave filled with water, where another cave entrance was visible shining through the water from underneath with a blue light, he explained.

One time, as a kid, he dived down to see what was in there. Once under, he saw the hole was massive, the size of his farmhouse. Swimming through, bursting for breath, he emerged out into the choppy open waters of Georgian Bay. Realizing he’d need to head back the way he came, he dived under again, but this time the hole was black.

“I didn’t expect this, so I swim through it, and my eyes get adjusted and it’s like, cave light and I come to the surface and there’s people in the cave, because there were other people around, and they’re like, ‘He’s back! He’s back!” he recounts, with the realization that those left behind — including his brother Bruce — feared he had drowned when he disappeared and didn’t resurface.

Experiences with psychedelics like those on the cliffs as a teen formed an integral part of his philosophy and attitude towards life, said Craig.

“We were never into using psychedelics like LSD or psilocybin or mescaline just to get high and have fun. Although I believe that is what happened,” he said with a laugh, and then paused to think. It was more about trying to find a higher consciousness or understanding the question of what life is, he added.

“I think I got that those chemicals took me to a place where I felt a oneness with everything. Once you feel that — for me — it never left. Timothy Leary said once you know the roadmap to that place, you don’t need the roadmap anymore, you know how to get there on your own.”

‘Saw first honey bee today’

The moment Craig knew he wanted to spend his life outside, growing things, came when he was in his 20s.

Born in Toronto, Craig hitchhiked into Nanaimo in 1978 at the age of 22 and had initially thought he would pursue filmmaking — he had studied film in Ontario, and that year his film “Gracie” won Best Student Film in Canada at the Banff Mountain Film Festival.

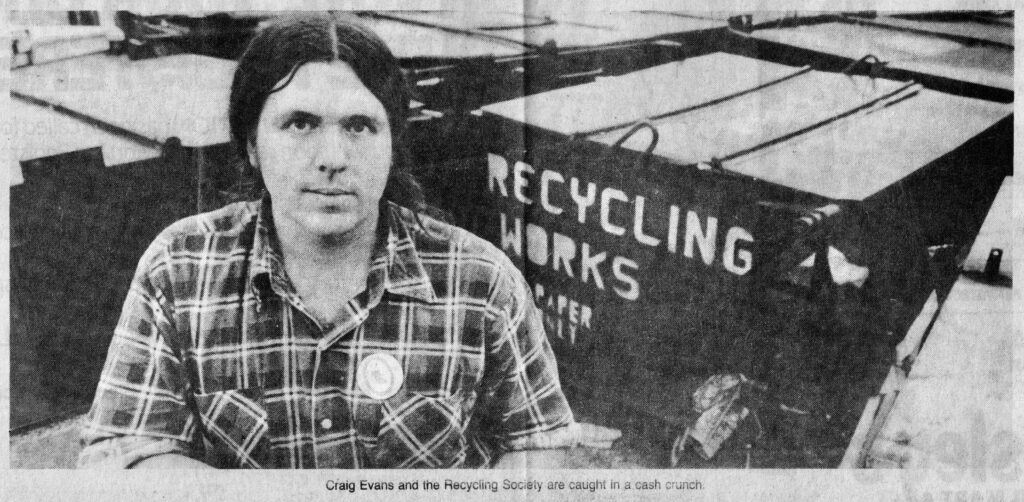

At this point in his life, Craig was also looking for more hands-on work, something he could join that could help the environment and “save the planet from going in a terminal direction.” When he realized that recycling aimed to deal with a lot of society’s excess waste, he was all in.

He was soon hired by the Society for Promoting Environmental Conservation (SPEC) to set up the first curbside recycling operation in Nanaimo.

What transpired was not only the precursor to what later became the Nanaimo Recycling Exchange — which he got off the ground at a time when few municipalities were even aware of what recycling was — but when it expanded into Saanich it grew to be the largest curbside recycling operation in Canada west of Kitchener, Ontario.

But it wasn’t easy. “It has been a constant battle all the way to balance government grants, look after the handicapped who are the principal employees, and keep the trucks working,” stated a 1983 story in Island Review Magazine, about Craig and the regional recycling movements at that time.

“[Craig] has kept recycling very much in the public eye, and won the support of local politicians for recycling to be officially endorsed and run parallel with the city-operated refuse system.”

One night at the recycling depot, Craig picked up a beautiful Indigenous art calendar that was mixed in with the recyclables.

“I go through, open the calendar, and the first thing I see is, ‘Saw first honey bee today.’ And I was like, ‘What? Someone marked that on a calendar?’ Then I looked through, more detail — ‘Seeded beets, seeded corn, seeded tomatoes. Weeded. First cucumber flowers out.’

“I had the whole year’s calendar in my hand. I saw that whoever owned this calendar had experienced the summer. Had gone through the seasons. ‘Picked 10 pounds of this,’ you know, ‘Put the beds to rest,’” he said.

“There I was, late at night in a warehouse, with tons of cardboard to bale. I was missing out on the summer. I was missing out on the seasons. And I was just like, whoever had this calendar, lived,” he said. “That was my goal. I thought, ‘That’s what I need to do. I need to just get out of my day to day… to be more in tune with what’s occurring around me.’”

By 1985, prices for paper, cardboard, glass and other recyclables steadily dropped, to the point where there were eventually no buyers. They kept collecting materials, which began to build up in the warehouse.

Eventually the city was pressured to put the recycling operation out to public bid and it went to a private operator.

This was disappointing, Craig said, but because they had run the operation as environmentalists he also viewed this move as a success: they had managed to get a private enterprise interested in the business of recycling. However this operator only lasted for eight months and then closed the operation down.

“After the recycling depot closed, I thought, well, I’ll put a garden in around my house. So I planted some things around my house. Then as I was weeding, growing, I realized how much peace and enjoyment and fulfillment I got out of doing those simple tasks. I felt as if I was connected with my ancestors who would have done very similar tasks, and I really felt good about the work I was doing. That’s what I was looking for. I was looking for work that would make me feel good inside.”

He soon enrolled in the two-year greenhouse technician program at what was then Malaspina College, though the methods of agriculture they were teaching in those days soon caused him to feel a sense of disillusionment. There’s got to be another way, he thought.

“I realized that I was being trained to grow food in greenhouses, how to manage workers, use chemicals, pesticides. To grow food as cheaply as possible and sell it as expensive as possible. And after I spent a couple of years learning that, I realized that wasn’t in my heart to do. I didn’t want to work for a five or seven acre pepper greenhouse with ‘solution A’ and ‘solution B’. Of course, every chemical we used to control pests in those days — it’s all banned now. Though we were promised it was safe, and told, ‘Why would you question Health Canada?’” he said.

To complete the program, Craig wrote a thesis on how to grow organic food in greenhouses with a worker cooperative to feed low-income people. Most students had written about how to grow commercial peppers, or tree seedlings. His instructor gave him a good grade, commenting that he’d “never seen this before.”

The reception to organic farming in those days was ignorance, or even outright hostility. Even as late as 1989, a Globe and Mail article headlined, “Organic Food Called Farming Threat” stated that “increasing consumer preference for so-called natural and organic foods threaten the farming industry,” according to the Ontario Federation of Agriculture, which requested help from the government to “combat the trend.”

For Craig, once again it all came back to, “What am I going to do with my summers, and the time that I have?” His conclusion was that the most important thing he could do was set up community gardens for people in need.

“I could use my skills to help grow and teach people how to grow food for their own use. And after doing that for a number of years, I realized that community gardens work pretty good. We should have community farms as well — a little bit larger scale,” he said.

He ran with this idea, and by 1987 had established Nanaimo Community Gardens. A decade later, he helped organize local food and local agriculture advocacy groups into a network called the Nanaimo Foodshare Society.

At times, much of these efforts utilized little more than what he called “a rag-tag army of believers” and a little ingenuity. “Don’t ask for permission, ask for forgiveness,” was the lesson he learned from these endeavours, and it extended into not just what he fought for — but what he also fought against.

‘Do whatever you freakin’ can’

While still in the recycling centre’s early days, Craig would go to the offices of forestry giant MacMillan Bloedel every Friday to pick up their office paper for recycling. Looking through these documents in detail at home, he soon realized that some of the paperwork detailed their future logging plans.

“They were going to [dump] logs in Robson Bight, where the rubbing beaches for the whales were. What the hell? They had all this pristine old-growth forest, for real. We were just like, ‘My lord, this cannot happen,’” said Craig.

The Tsitika River Estuary, in Tlowitsis Nation territory, a few hours drive north of Campbell River, was one of the last intact watersheds on Vancouver Island and a crucial habitat for orca whales. “We organized whale watching tours right away. ‘Come on, let’s go to Telegraph Cove, we’ve rented a boat, we’re going to do whale watching tours.’”

They contacted all their environmentalist friends and organizations in Vancouver, including renowned whale researcher Michael Bigg, Greenpeace and what later became the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, and immediately set to work.

“I’ll never forget, CBC Radio calls us — we’re a little recycling depot and environmental organization — and says, ‘What the heck are these whale watching tours? Who wants to go watch whales?’” Craig said with a chuckle.

By 1989, Craig had a new fight on his hands when New Jersey industrialist Jay Wooding rode into Nanaimo after being chased out of Bamberton with millions in secured funding and near-certain approval to install a ferrochromium smelter at Jack Point, right on the Nanaimo River estuary, the heart of Snuneymuxw territory.

“The concerns in Nanaimo have been that this is just going to be ramrodded through without adequate environmental protection,” said NDP MLA Jan Pullinger in 1989 when she addressed the issue in the legislative assembly.

Potential problems with the plant included the leaching of carcinogenic materials into the surrounding environment, the dumping of tens of thousands of tonnes of slag on the property and the lack of a functioning prototype of the plant, she added.

Craig helped spearhead an offensive against the plans, and overwhelmed Wooding’s public information session with opponents armed with their own informational pamphlets and posters.

Members of the local university theatre department showed up with signs and joined the protest.

Forming a group called the Citizens Public Action Committee, Craig and others then hosted a town hall panel discussion to answer the community’s concerns, which was attended by hundreds of local citizens.

Realizing the weak point in the enterprise’s armour — that the project lacked a full phase three environmental study, as per federal regulations — Craig wrote to then-environment minister Lucien Bouchard to explain the situation, and included the expert reports and data they had commissioned and researched on the project.

The study was ordered, and Wooding backed out.

There would be countless more battles on the horizon, including a successful push to halt plans for a proposed waste incinerator that residents feared would pollute local air quality, and the eventual protection of Colliery Dam as a popular swimming hole and green space in one of Nanaimo’s poorest neighbourhoods.

In every situation, Craig utilized whatever he had at hand.

“You just do whatever you freakin’ can,” he said with a grin. “You gotta.”

‘A little bit too loud and a little bit too long’

Craig loves to tell stories, and one of his favourites is about how he met Jen Cody, the love of his life.

It was Sept. 10, 1999 and he was invited to a now-historic food security conference in Sorrento, Secwépemc territory, that resulted in the founding of the B.C. Food Systems Network.

The intention of the conference was to gather leaders from all over B.C. working in the field of food security and agriculture — from those working in pregnancy outreach groups to food security to those working in community kitchens and gardens to Indigenous food systems groups — so they might coordinate their efforts in a push to influence policy at a provincial and federal level.

“That first night we all walked into a banquet hall. I’m like, holy cow, I’m scared. There’s so many people here. And somewhere in the crowd I could hear this woman, and she’s laughing — just a little bit too loud and a little bit too long — and I scanned the crowd, like, where’s that sound coming from? And then I saw Jen. Like seriously, from across the room I saw Jen, and she towered over everyone,” Craig recalled, his face breaking into a smile. “I remember looking at her and thinking, that’s the one.”

With her own extensive history of working in agriculture and food security advocacy, specifically for pregnant women and mothers, Jen now works as a dietician with Nuu chah nulth Tribal Council and serves as a leading force behind the Growing Opportunities farm projects.

“There’s a number of blessings that come from this, in the way that it has,” said Jen, as we had tea in her kitchen one afternoon. Though they may not have a choice in Craig’s death, they do have a chance to make the most of the process, she added.

She told me about a recent meeting they had with a representative from Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) program, to look at what options existed for him. When Craig learned that the patient is put to sleep prior to their death, he asked if he could be awake during the process, to be a conscious participant in his own death.

“She just kind of looks at him and goes, ‘No one’s ever asked me that before,’” said Jen, with a laugh. Turns out it’s not so easy for MAID to change their protocols, so his request is unlikely. “But that’s just so Craig.”

One thing about the advance notice of terminal cancer is that it offers the opportunity to sit back and assess what’s most important, said Jen.

“I want to make sure that the time that we have together is time that’s focused, and that things aren’t left unsaid or undone.”

Though the loss of who she describes as her “soulmate” is intense, she wants to focus on the gratitude she has for the more than 20 years they spent together rather than the time that was cut short. It’s a sentiment they both share.

“I learned at a very young age there was probably a time when I would most likely die. So it’s not something that I avoided over time, it was something I became comfortable with over time,” Craig agreed.

“People could say, ‘Oh, well, there’s that fear of missing out, or fear of what’s going to happen next.’ That’s not for me to fear. My time here is for me to experience wonder and just the joy of being here. This is the miracle we were all hoping for.

“I’ve been so fortunate. I actually can’t think of anyone who has had as much fun as I have had in just living day to day, having lots of projects to work on that I believed in and was able to move forward.”

In the time they’ve had together, there are many things Jen has come to appreciate about Craig, who she simply describes as “the best human I know.”

As an example she points to his “uncanny” ability to show up at pivotal moments in people’s lives — like he did in mine — to help them “pull it together” and get to a foundation of safety and stability from which they can then go in a more positive direction.

“Then all those people are threaded and woven together in a web of folks that are all like, ‘My life vision is to work for community benefit.’ All of the people who are connected to Craig, I would say, are part of that community network. Folks who see the value of community, and then their trajectory in their lives is building community, from that foundation that he helped create,” she said.

During two community gatherings held in November to celebrate Craig’s life and contributions to the community, people shared stories about the ways he had helped them.

Aimee Chalifoux was one of those people. Today, Aimee is the executive director of Literacy Central Vancouver Island, a long-running organization that runs a number of programs that promote literacy in the community.

For decades, she has worked as an advocate for Indigenous and marginalized residents and was recently recognized at the B.C. Multiculturalism and Anti-Racism Awards in 2021 where she won a Breaking Barriers award.

However her life as a teenager was very different. At 15 years old she was a self-described “feral little street urchin,” out of control and angry.

She had just run away from the Nanaimo Youth Services group home when she met Craig through her friend Carrie’s mother, and ended up renting a room from him.

“Growing up as an Indigenous girl in foster care here in Nanaimo, I took my fair share of racism. I’m just going to call it what it was. I was often the only Indigenous kid in my class, in school, anywhere I went, in my neighbourhoods. So I grew up with a really big chip on my shoulder and I was quite small for my age, so I became quite scrappy,” she recalled, during the community event to celebrate Craig at Cavalotti Hall on Nov. 19.

“Craig was the first male in my life that was safe. I did not have safe men in my life back in those days, and he was one of the very first. And he introduced me to all kinds of safe people. Craig’s home was happy. It was joyful.

“You didn’t get a free ride there though. You worked, even if you had been partying until 4 a.m. We got up out of bed and went out to the farm with Craig. I remember being in the hot, hot sun planting tomatoes and being very ill, but I also knew that I was going to have a safe bed that night,” she said.

They worked hard but also played hard, she said, spending days at the farm and afternoons swimming with friends in the Nanaimo River.

In the evenings they made food gathered from the farm and salvaged out of dumpsters, and played air guitar to loud music in the living room.

“I had never danced in a kitchen until I met Craig. He taught me a lot about what community was. I did not know anything about sharing. Like I said, I was feral. I was wild. I was in full-on survival mode, and if you turned your head for a second, if you had food or money it was gone.

“For the first time, I lived under Craig’s roof with many other people, and we didn’t steal from each other. I never stole from Craig, ever, because he was this beautiful man who came out of nowhere who was all peace and love. And I really questioned him at first, like, this guy has got to be crazy,” said Aimee.

“Through the years, Craig and I may not have seen each other all the time on a regular basis but when we did, it was never weather talk. It was never small talk. It was, ‘I love you man. How the hell have you been?’” she recalled, holding back tears. “Craig is one of the realest people I ever knew.”

‘The torch is being passed’

When Nanaimo physician John Cline and his wife Joy told their children about his plan to buy a 47-acre farm and move his practice there in 2018, he said his daughter’s response was, “You’re what? At your age? You’re crazy!”

“But that’s exactly what we did,” said John, speaking at the Vancouver Island University event hosted by the culinary arts department in Craig’s honour on Nov. 10.

Though he comes from a long line of farmers, John himself has no farming experience. After purchasing the property, he said their marketing plan essentially amounted to saying, “God, this is your land. You bring onto this farm the people that you want here.”

So far, “it’s worked out pretty well,” he laughed.

Not long after setting that intention, John said he and Joy met Jen and Craig through the local farmer’s market and invited them to set up on the farm.

“As we go through life, it is rare to meet people of high integrity, and Craig is one of those people,” said Cline.

Four and a half years later, the Cline Agri-Health Centre is home to a variety of projects run through Growing Opportunities as well as through local senior’s groups, churches and non-profit organizations. One of the barns serves as a youth activity centre that runs summer camps for youth.

One of Growing Opportunity’s most recent projects was to partner with Nanaimo Association for Community Living (NACL) to create a new community-supported agriculture box with funding from the Canadian Women’s Foundation.

The initiative is run by women farmers and is intended to create as many hands-on opportunities for workers of diverse abilities in all aspects of their production. Profits from the sale of these boxes at market rate will enable more produce to move into subsidized food box programs throughout the central Island.

Established in 1864, the Cline farm, formerly the Westwood Dairy Farm, is one of Nanaimo’s oldest. Cleaved by the Millstone River, the farm borders the city-owned East Wellington park.

When we walked the property this summer, Craig said his ultimate vision was for the entire 77 acre area — both the Cline property and the city-owned piece adjacent — to be slowly transitioned into active farmland and managed solely for the food security needs of Nanaimo’s residents.

This vision also fits with Jen and Craig’s success in lobbying the city to save Five Acres Farm, one of the last intact parcels of agricultural land in Harewood.

Part of a coalition that pushed for the city to permit Nanaimo Foodshare and Growing Opportunities to use a portion of the land to grow food and host workshops, their efforts resulted in the city’s purchase of the land in 2019. At present there are some plans for a park and some housing on the property so its longterm future as a site for farming and food production is still uncertain.

Though Craig’s work filled a huge space in the community, Jen said “the torch is being passed” and a transition team has been established to ensure Craig’s work in food security and with Growing Opportunities continues.

There is also room for people to step up, get involved and honour his memory, she said — whether it’s at the farm or within their own lives. Another way to support Craig’s legacy is through a memorial fund that has been established in his memory through NACL, she added.

“I’m just really encouraged by how people are working together to try and achieve the greater purpose,” said Craig, who added that he had “caught a few batons” from elders when he was younger, and understood the message and wanted to run with it. “Now, my goal is just tossing the baton — or a series of batons — to other people to run.”