This story discusses intergenerational trauma, suicide and drug use. If you or someone you know needs mental health support call 310-6789 (no area code required) or 1-800-SUICIDE (1-800-784-2433).

Nanaimo hip-hop artist Sirreal has spent more than a decade connecting with his listeners through honest and vulnerable lyrics. One of his hit songs, How Many More, featuring acclaimed vocal artist Raymond Salgado, opens up dialogue on tough topics such as addiction, depression and suicide.

With lyrics like, “The journey is short, but the road’s long / How many more got to go before we start to see what is so wrong?” Sirreal’s messaging is authentically raw, and it resonates. His YouTube videos are filled with comments from people sharing personal stories and heartfelt messages.

The Discourse’s Rae-Anne Guenther sat down with the person behind Sirreal, Matt Dunae, to learn more about how his own story informs his music and advocacy.

‘I just wanted to hang out with my mom’

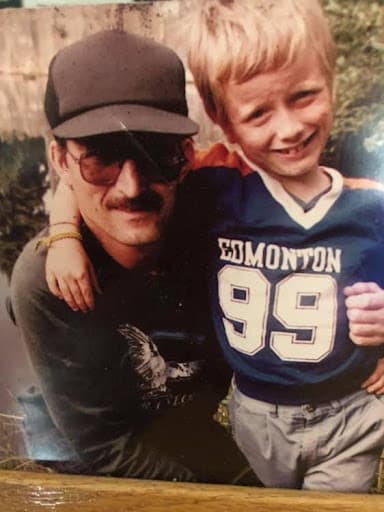

Growing up in poverty and surrounded by addiction and mental health issues, Matt’s childhood was entrenched in intergenerational trauma.

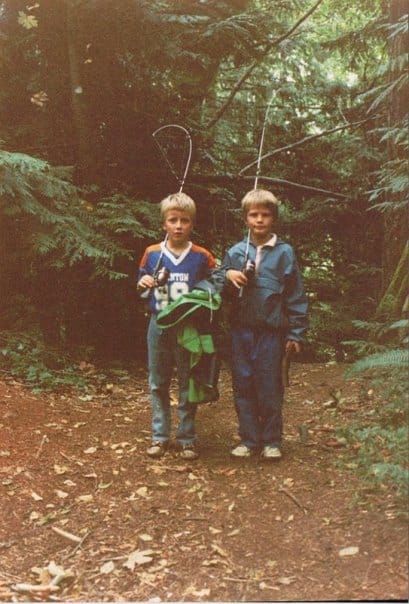

Since he was three years old, Matt and his older brother Nick would rotate back and forth between the child welfare system and living with their parents.

Growing up, Matt felt his mom was a saint and embraced the freedom she gave him, like being allowed to stay out all night, smoke or skip school.

“It wasn’t until I got older, I realized like, oh wait, that wasn’t a good environment at all — that was super toxic,” he says.

At 11 years old, Matt tried crack for the first time with his mom and her friend. He was instantly addicted.

“It was one of the only times I got to hang out with my mom,” he explains. “I only discovered later in life after doing a lot of self-reflection that I just wanted to hang out with my mom.”

Due to his addiction, Matt dropped out of school and began committing crimes. It wasn’t until his father died by suicide that he realized the path he was on could lead to his death.

Matt made the conscious choice he wanted to live, and at 15 years old, demanded the police place him in foster care. He began to turn his life around, while his brother decided to stay with their mom to take care of her. After missing almost four years of school, Matt worked hard to catch up to his classmates and graduated high school.

Even though Matt clawed himself out of poverty and addiction, for a long time he was weighed down with resentment towards his mother for raising him in a toxic environment.

But over time, Matt says he came to understand that people give the best they can with what they have. Matt’s mother was an orphan at two years old and had been severely sexually, physically and mentally abused throughout her childhood and adult life.

“She’s had a really hard life. I can understand some of the reasons why she is the way she is,” explains Matt. “I actually appreciate the fact that I can understand that, because it allows me to love her as a human being.”

Related: Kids of addiction: What my father’s overdose death taught me.

‘Break those cycles’

The continuity of trauma from generation to generation has been well documented by researchers. Children who experience potentially traumatic events like abuse in the family, (known as Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs), are more likely to live with chronic health conditions, mental health issues, addictions or face barriers like unemployment later in life.

Though every child is unique, adverse experiences can include neglect, mental health issues among parents and extreme poverty — basically anything that disrupts the foundations of health. The higher the number of them (and the younger they are experienced) the greater the risk. And people who are exposed to this kind of stress may be more likely to have children who in turn experience adversity.

Many experts believe that addiction in particular is best understood as an adaptation to trauma in early life. They are “attempts to regulate our internal emotional states because we’re not comfortable, and the discomfort originates in childhood,” renowned physician and addiction expert Dr. Gabor Maté says in an interview with California Healthline.

On the flip side, healthy relationships and supportive environments that boost a child’s sense of connection can protect against these adverse outcomes. For this reason, public health officials and researchers are actively exploring family and community supports that can break the cycle of harm.

For Matt, music was the medicine. He has been writing music since he learned how to write. Though he grew up listening to rock and blues he gravitated to hip hop (a cultural movement founded by Black inner-city artists in the 1970s) watching local rappers like the Telepathics, a group that included Rob The Viking.

His brother was his biggest fan. “I was a terrible, terrible rapper when he was listening to my stuff. He would go and burn 10 CDs of mine, and then go and hand them out to people in his neighborhood and tell everybody I was the best, tell them I was going to be the number 1 rapper in the country,” he explains. “If I had half the belief in myself that he did in me, I would have been good.”

‘That’s the medicine’

As Matt gained confidence through his music, he eventually voiced how he felt being raised in that environment to his mother.

“And she looked over at me and she was like, ‘I’m sorry I never gave you a chance to be a decent human being, the way I raised you.’ It was like all of this weight just magically lifted off my body. It doesn’t make my blood boil anymore, because I’ve let go. It wasn’t affecting her; it was only affecting me.”

Matt managed to stay clean until his early twenties when he experienced a relapse (a normal part of the recovery process). He showed up at his brother’s house intoxicated and was met with understanding and acceptance. Nick took care of him that night with no judgment. That was the last time Matt used drugs.

“I was just like, how can this guy show such unconditional love for me, given how I’ve treated him sometimes, you know?” he says.

Shortly after that encounter, in 2007, Nick Dunae took his own life. To say a proper farewell to his brother, Matt booked three hip-hop shows to raise money for the funeral costs. The community believed in Matt’s cause and his music: He raised $8,000 in those three shows. The unwavering support Matt received made him realize he needed to give back to his community in some way.

In 2018, Matt’s fans helped him win a Sunrise Records contest that included 500 prints of a CD and LP. Matt used that opportunity to dedicate an album to his brother, but he needed to submit a demo that week. In three, 16-hour sessions with his producer Rob the Viking, Matt created the album In the Nick of Time.

Fulcrum Interlude is a free-flowing spoken word track off that album. “I went into the booth, recorded it in one take, and came out crying like a baby,” says Matt. “My brother’s guitar playing and voice is featured on that song, which we ripped from a cassette tape he left behind.”

In the video for the title track, Sirreal uses the theme of the Walking Dead series to speak up about conquering our internal demons.

The birth of Matt’s only son Benny in 2008 was another saving point in his life, and the video shows his son saving the day just “in the nick of time.”

To further honour his brother, he used the album release to fundraise to make a wider impact.

“When you’re going through something you feel like you’re the only one that’s going through it. But that’s not true, right? There are so many other people that are going through almost the exact same thing as you’ve gone through, but you just don’t know about it,” explains Matt. “Having an open conversation with everybody else…that’s the medicine, right?”

This medicine is captured in the track Words like Weapons, released in 2014, featuring local musician Jona Kristinsson. The lyrics and video tell the story of two kids turning to words and music to overcome the pain of being bullied.

In it, he rhymes: “Not knowing what he’s going through at home / in a room full of people you can still feel so alone.” Linking our shared experiences — positive or negative — is what Sirreal aims to achieve in every song.

‘It’s all about connection’

In the months following the death of his brother, father and two close friends, Matt felt alone in dealing with the loss of so many from suicide. He stumbled upon an event downtown one afternoon hosted by the Vancouver Island Crisis Society called Souls Remembering Souls. As he walked and talked with others experiencing similar pain, he began to realize the healing power of connection.

In any year, one in five Canadians experiences a mental illness or addiction, according to the Canadian Mental Health Association. In Nanaimo, regional health data shows that mood and anxiety disorders and depression are the most common chronic diseases. As Matt relays in one of his music videos, an average of 11 people die by suicide each day in Canada, according to national statistics.

As an extension of that grassroots event, the Crisis Society has now developed a department devoted to Suicide Bereavement Support Services which includes a no-cost, monthly support group and one-on-one counselling.

The program coordinators of the Crisis Society called Matt later on to ask if he would attend their program GRASP (which stands for Growth, Resilience, Acknowledgement, Suicide Awareness, Prevention and Personal Planning) and speak to the kids.

“They told me, ‘One of the kids was a rapper. He wrote a rap song about the program and we mentioned your name, and he said he was your biggest fan. So it would be awesome if you came out and then showed up and just talked to the kids,’” Matt explains.

For six years, that is what Matt did — he toured schools everywhere on the island, performing his music and speaking to youth about suicide. Matt estimates he has talked to over 10,000 youth.

“In the time since Matt was with us, we have again expanded our programs to meet the changing times, and have included a popular spoken word poetry component to the work,” says Lyndsay Wells, community education program coordinator for the Crisis Society.

“Research tells us that writing and performing poetry is a highly protective and effective coping practice for young people,” she says.

“I just wanted to give you a shout out and say I love this song it really touched home…My favorite uncle committed suicide a few years back…I lost so many downtown friends to overdose, addiction, suicide and more… I thank God everyday I made it out of all that scene alive.”

—YouTube comment on Sirreal’s track How Many More

In response to COVID, the Crisis Society collaborated with a Vancouver-based filmmaker to create their first online suicide prevention program, COPE, which was delivered last year through an app to about 1,400 students across the island, says Lyndsay.

Last year, the organization supported more than 40,000 interactions – of those, nearly 2,000 were through text message.

During his time at the Crisis Society, Matt also became a facilitator. In the beginning, he would write on a clipboard everything he could think of to say to ensure no one died by suicide.

“I realized after a year… I had to put the clipboard down. It’s not what you’re going to say. It’s what you’re going to help other people say,” Matt explains. “Because only then, during that discourse, can you have healing and have it leave your body and have it processed correctly.”

Soon Matt was helping facilitate crisis interventions and skills training like safeTALK, (which empowers people to identify and support others who are having thoughts of suicide) for nurses and members of the police, military and navy, who are exposed to traumatic events and respond to suicide incidents.

“Here I was coming from being a drug addict, poor kid to now shaking hands with admirals at the navy base — with blue hair,” he says. “It was a real eye-opener to me that it’s all about connection. Creating connection from the experiences that you’ve had, instead of blaming the experiences that you’ve had for who you are. Take those experiences and use them as inspiration to change and break those cycles.”

Matt now works as an outreach support worker. He facilitates workshops centered around connection and trauma. He also created a Facebook page, the Real Ones, to act as a safe space for people struggling to connect and is creating a podcast with friends about trauma and healing.

His latest works, The Blue Album and The Red Album, featuring his live band Blue Satellite, express both the light and dark of his personality and experiences. The Red Album was released on Aug. 28, the anniversary of the death of his father. He released the video for the track Get the Money featuring Revron & Switch on Oct. 8.

Above all, the most meaningful pathway to healing Matt has is with his 12-year-old son Benny, who is featured on a series of tracks, including Shooting Stars (A Father’s Love), released earlier this year.

In the track, Benny, a.k.a. Lowercase G, raps about the aftermath of a broken family.

“It’s a lot to handle as a little kid / …play it back but there’s no taking back my innocence /In a sense it makes me stronger so I thank my mother / Put no one above her / Now we help each other / Work together to help one another to recover.”

Matt says he intentionally lives his life to ensure Benny never experiences poverty, abuse or neglect like he did.

“It’s almost like I had to go through those trials and tribulations, just so he didn’t have to. So I’m grateful for that, you know, at this point in my life, and it’s taken me until now to be completely grateful for it.” [end]

There is help

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 911, 1-800-SUICIDE or 1‑888‑494‑3888 for the Vancouver Island Crisis Line 24/7. Crisis text is available at 250-800-3806. You can also call 310-6789 (no area code needed) for mental health support anytime. The Kuu-us crisis line (1 800 588-8717) provides culturally specific assistance for Indigenous people.

If you’d like to volunteer or get training with the Vancouver Island Crisis Society, more information can be found on their website.

Editor’s Note Oct. 14: This article was updated to clarify the age that Matt Duane asked to go into foster care and the nature of his father’s death.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter, Nanaimo This Week, to be the first to know about our in-depth local stories.