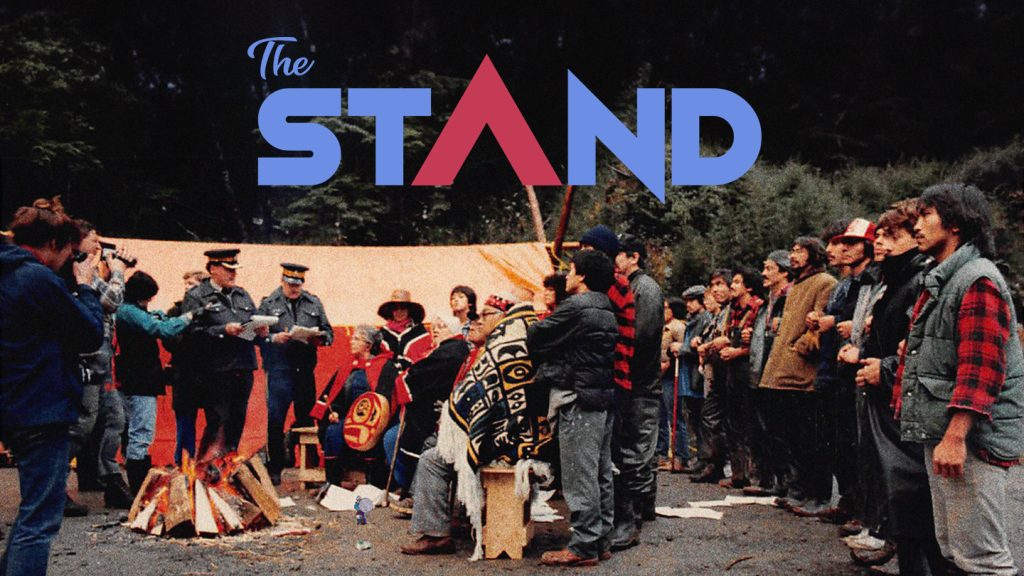

A new documentary about the pivotal 1985 Haida Gwaii blockade has a strong connection to Nanaimo. The Stand is a documentary by Haida filmmaker Chris Auchter, produced and distributed by the National Film Board of Canada, that was screened recently by the Nanaimo International Film Screening Society at the Vancouver Island Conference Centre.

Auchter is best known for his 2019 film Now is the Time about Haida artist Robert Davidson.

He also worked as an animator for the 2009 short film How People Got Fire as a video game and TV animator and released his debut animated film The Mountain of SGaana in 2017.

One of the main characters in the story is Frank Beban, a settler businessman who owned a Nanaimo-based forestry company that had a contract with Western Forest Products to log on Lyell Island in Haida Gwaii, also known as Athlii Gwaii.

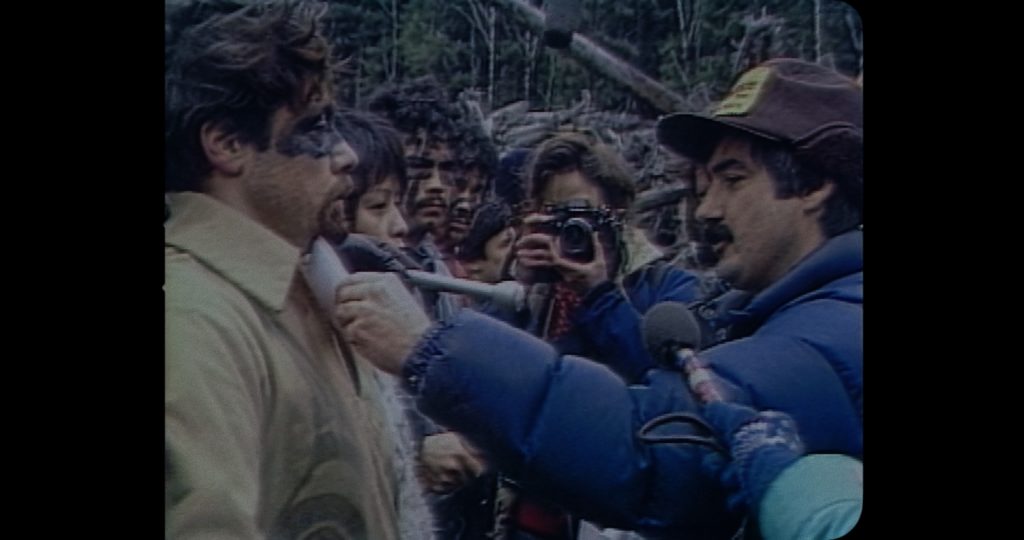

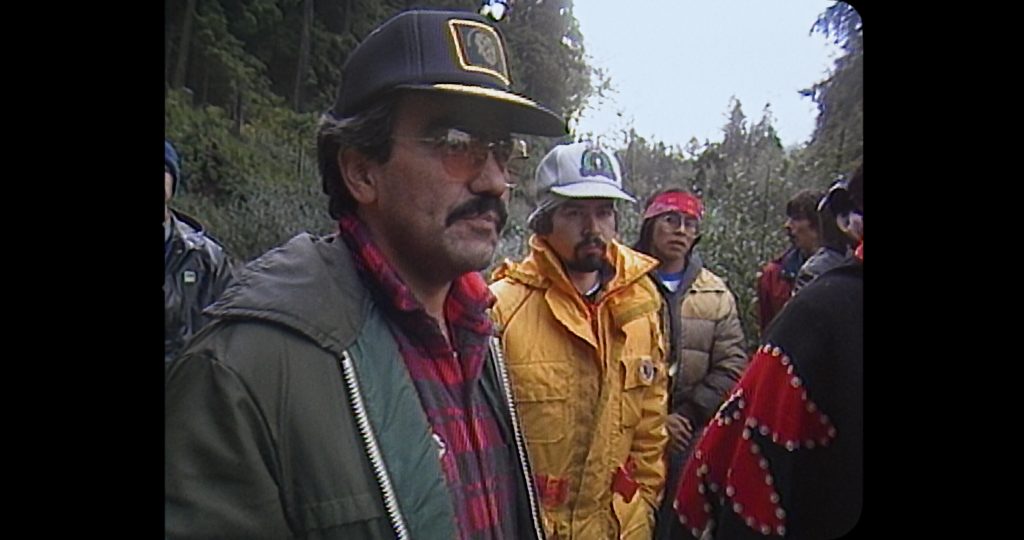

The film uses archival footage to tell the story of Haida land defenders who defied court orders to block logging companies’ access to their land resulting in the transformation of about 1,470 sq. km of Haida Gwaii into the South Moresby National Park Reserve.

The Nanaimo International Film Screening Society’s Lisa Chew spoke with director Chris Auchter about the film in a video interview that was shown after the screening. The film will also be shown at the Victoria Film Festival on Feb. 11. We are pleased to bring you a lightly edited version of the interview below.

Lisa Chew: The Lyell Island Blockade is an event that has multiple layers of connection for you. Could you tell us about these personal connections and how they influenced your storytelling approach?

Chris Auchter: Yeah, it does have a large connection. The closest connection is members of my family who were there fighting on Lyell Island. My uncle Mike was there, Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, who’s a huge influence on me and is an artist as well.

And then my Auntie Shelley, who’s really close to me, she was down there as well. So I grew up knowing that they were down there, but that’s about as far as that went for me. I didn’t really understand too much beyond what Lyell Island 1985 meant and how the Haida were standing up to the logging companies and to the governments of Canada and British Columbia. So when it came time to create a new film after Now Is The Time, I was thinking it’d be great to honour them in some way.

I didn’t know much about this story, I thought I should maybe learn and this would be a great way to do that is to make a film on it. That started the journey.

What were some of the obstacles that you encountered while you were making the film, especially given that it had personal connection?

There was so much for me to learn. I didn’t really know much to begin with so I read a lot of different books. I read a book that was all about Guujaaw who for a long time was our president of the Haida Nation and a big figure within the film, he was the one that was teaching everybody how to sing.

So I read the story about him. That gave some great context in terms of some of the history that was taking place on the island. I was collecting audio from the BC Archives of various interviews from different Elders and I was just trying to gather information to try to piece together what was going on in this time, even before 1985. I trying to became almost like an authority to be able to tell the story.

Then there was all the footage that I was able to gather that was taken from Lyell Island so that I could keep us in 1985 and just really immersed in the moment. And then the people who were there could be the storytellers. I could let them explain and tell their story. I thought that was the most truthful way to do it, even better than having new interviews from today because that was them living those tense moments and showing that bravery and why they were doing this. Even from the various loggers being able to see their thought process and how they were handling the situation.

One of the questions I asked myself early on was, ‘Can we do this film just by keeping it within the footage of the time?’ One of our first goals was to see if we could do that with all this footage we had. So we had some editing time early on in the process to be able to answer these questions before we went into production.

You mentioned the singing and actually it’s something I noticed right away when I was watching The Stand. Can you tell a bit about your use of music in telling the story?

So the music is by Genevieve Vincent. We worked together for the first time on Now Is The Time. She just blows me away with her abilities. One of my favourite parts of the filmmaking process is getting to the music because it brings so much to the picture. And you just get to be immersed with all these extremely talented musicians as well, which is exciting. They’re like rock stars. The opening scene, for instance, I really wanted the idea that something is wrong, there’s something in that forest that’s not right. The music carries that quite heavily in terms of that the animals are reacting and it’s pointing towards the forest.

I noticed the drums and the rattles, when the Elders arrived the tone of the music for that.

That brings up some great points too, in terms of being able to use it as a bit of a storytelling device. When the Elders arrived, that was a real tense moment. It was a windy day and it was stormy. The Haidas knew that there were no reinforcements coming because it was too windy for boats and they thought even the planes. But then this helicopter’s coming and this is just after they defied the court order to get off the road.

So my uncle Mike was telling me, ‘What the heck is this helicopter? The SWATs coming to teach us Indians a lesson?”

And it lands and out comes the Elders. They didn’t know the Elders were coming. It surprised them. As Christopher Collison said, the loggers could have just turned around and walked away that day. It was over, they weren’t going to budge their position after the Elders showed up. It gave them so much strength.

But this idea of using the music to be able to tell that story, even though we didn’t have that story to be able to tell verbally, we could show that there’s this tension and the music has all this scrunched up tension that doesn’t release until the Elders come out of the helicopter. And then it releases and then it’s almost like you yourself as the viewer can breathe again. The Elders are here! And that’s the beauty of music.

You are primarily an animator so I’m wondering why you took a more restrained approach when you were using animation in this film?

I didn’t want it to take over the film because I wanted it to primarily showcase those that were there and living the moment and having them be able to tell their story. But I wanted to incorporate an element of our culture, which was a big facet of why the Haida were doing what they were doing. They were trying to protect our culture so that it could go and move into the future. And Mouse Woman was a big part of that through the supernatural beings and this connection to the land and how much it brings to our culture.

I kept it fairly subdued but at the same time I was able to use Mouse Woman. It became like the story was being told through from her perspective. She’s witnessing all this. She’s giving us that information that we don’t get to see, in terms of what happened in the courtrooms. And it made it so that we could keep the film on the road at Lyell Island.

I understand there’s lots of different supernatural beings that inhabit the Haida land. So what is it about Mouse Woman and her character in particular that made her the right fit for this story?

Mouse Woman is a real pull-in for me in terms of our stories and what she does. She’s like this little figure that won’t be shoved around. She’ll speak her mind and she’ll help if there’s a Haida person who has found themselves in trouble — -n most cases it’s their fault because they’re being disrespectful or something — but she’ll still help them and help them learn and grow and help them to make it right again.

She became, for me, the perfect supernatural being to represent all of the other supernatural beings that I think were there helping to give the Haida strength to stay on course with their plan of nonviolence, and to have the steel to be able to stand on the road, not knowing how bad this was going to be for them when they were arrested and showing so much courage.

I found the feast event with the Haida and the loggers a very moving part of the story. What do you think it is about sharing food that was important to this situation?

That was definitely about mending fences and trying to keep that relationship strong, because they are neighbours and even members of the community. Everybody’s a member of the community. We all live together.

So were the loggers living on or near Lyell Island at the same time this is all going on?

A lot of them would have been. There was the camp, or town, on Lyell Island. But a lot of them were flown in from different parts of B.C., from Nanaimo and from the Interior.

There were Haidas who were working for Frank Beban and it was a real split in terms of which side you were on. The community was split down the middle. Some people weren’t talking to others. Businesses were boycotted because they were supporting the Haida. I’m not sure, but maybe it happened vice versa, too.

This was a way to mend the differences. It’s that breaking of the ice when you’ve had a big argument and being the one to kind of go, ‘Let’s talk about this. I’m sorry about the way it happened as well. Let’s figure it out.’ Trying to keep that line of communication open, which was such a big deal for this whole thing to happen the way it did. The communication lines are open with the RCMP and with the loggers. For it to be able to happen like this it seemed like everybody needed to be able to communicate with each other so it didn’t get absolutely crazy.

I heard there was a story that included food for the main RCMP officer as well, that he had eaten with the people and that there’s something about eating together and cooking for one another.

Exactly. Inspector Harry Wallace, he’s the officer that we see most of the time, he’s the one who explains what the charges are going to be.

I was able to talk to him while everything was being made and he told me a story that the first time he came to Lyell Island, they were on their boat, it was rough and a lot of officers were seasick. They landed right in front of the Haida’s camp as they were making jaam, which is halibut soup. They offered them some halibut soup and he said it tasted so good he asked for seconds. He said he could see their faces light up when he would ask for seconds because they could see he was enjoying the food and they loved that.

He said that that was the perfect way to start this whole thing just on this civility and sharing food.

Recognizing the humanity in each other primarily before everything else.

Even though the RCMP were staying in Frank Beban’s logging camp, staying in Bebantown, which I came to call it. He said that he made sure that he would try to go to the Haida camp as well to have coffee and have conversations as much as possible.

Do you think that kind of relationship during this conflict could happen today? Or do you think this was unique to this setting?

No, I think for sure it can happen because there were examples of protests done or stands done totally different that ended up in violence. I was watching a National Film Board film from before the Haida stand back East, I think in Newfoundland. They were trying to make an area into a park and people were flipping a police car and stuff. It was crazy.

There are examples of stands that we see today, like what happened in Wet’suwet’en Territory over the pipelines.

I think this can be an example of how it can be done. The RCMP and people in authority can look at this and go, look at what Harry Wallace and his team did and everybody treating everybody with respect.

It was really well planned out by the Haida. They went through different scenarios and situations and how they can handle this and went, ‘No, that’s not going to work.’

I asked my uncle and he said Gandhi was very much an inspiration for them, [especially] when some Haidas would get a little too energetic and step out of what they were doing.

There was this one story of one Haida who was running through the forest and he grabbed one of the faller’s lunches and opened it up and let all the ravens get at it and eat all of his lunch.

And he came down to the Haida camp and was kind of boasting about this and one of the Elders heard it and said, ‘You make a new lunch and you go bring that faller their lunch.’ So he made a new lunch and he brought the faller a lunch.

That was one of the stories of situations where the group would come in and go, ‘No, we’re not doing it that way. We’re doing it this way.” And the individuals that maybe got a little too excited would fall back.

They just really stuck to the plans of nonviolence. Because it was essential to get the support of the communities outside of Haida Gwaii. Because if you start yelling and being angry, you very quickly lose that kind of support.

So for those in our audience who won’t know the details, what are some of the lasting legacies of the Lyell Island blockade for the Haida?

A big one is called Gwaii Trust and it’s a huge funding body on Haida Gwaii today. It doesn’t just fund island projects in terms of Haida Gwaii for the Haida community. It funds all the communities of Haida Gwaii, whether it’s Sandspit, Port Clements, New Masset, Dadjingits, Old Masset or Skidigate. There are members on the board from each of those communities, so everyone’s represented and projects are selected and funded.

That came from Lyell Island in terms of some money that was given to the Haida from all of this. They started the Gwaii Trust with that. It was money that was supposed to go to a park. And even though a park was eventually made, the Haida and parks run it together in partnership.

So that was a big thing. And obviously B.C. recognizing Haida title was a big one. The film was almost done. We were weeks away from locking the film and this news came in and I’m okay, we’ve got to make some changes here. Hopefully Canada will follow suit soon so I can add another card onto the end.

Even using the words Haida Gwaii, I still remember — because I’m old enough — in the 1980s people started to use those terms and it was so awkward, “it’s Queen Charlotte Islands.” So the fact that it is just Haida Gwaii and that it doesn’t feel uncomfortable is beautiful, right?

Thank you for bringing it up because that’s so true. Even something that seems as small as the name is not that small. Like you said, it felt awkward to say it. And even for myself, I remember the first time my uncle Mike said, “We’re not saying Queen Charlotte Islands anymore. We’re going back to its name, Haida Gwaii” and it took me some time to be able to say Haida Gwaii. I’d say Queen Charlotte Island and my uncle might give me a look like, ‘No.’ So I’d have to get it right and say Haida Gwaii.

To bring it back into what was in the film, like with Guujaaw saying “Haida Gwaii out” and or “just fly past B.C. on your way to Haida Gwaii.” That was radical. People hadn’t heard that before, it wasn’t the norm. So even him saying that within the film was not normal.

So much has changed since then, when I think back to the Jack Webster clips and the perspective of your average British Columbian and the discussion around Aboriginal Title at that time.

Exactly. There were quite a few of those. I think it made people proud as well. Diane Brown’s dad Watson Pryce, who was one of the Elders that got arrested on that day, said that he was really quiet and never showed his Haida side that much. But after all this he started speaking Haida a lot more, he started telling her stories and teaching her some different songs.

What do you think the Lyell Island blockade story offers to teach those who wish to protect the land today?

It offers a real example of how it can be done. I call it Ada’s message. The final song in the film that plays over the credits. It was her speech that she gave to the youth on the hill after she was arrested. I think that can be a message, whether we’re fighting for the land or just living our day-to-day lives, is to treat each other with respect and to love each other. I think that was just a great way to leave the film and encapsulates what this is all about. We could have differences, but we can still treat each other with respect and not go to hatred as our response.