The memory of lining up around the block in the cold to attend one of iconic music store A&B Sound’s legendary Boxing Day sales downtown in the 1990s is a fond one for many of Nanaimo’s longtime residents.

However it was not a tradition that would last forever.

By the summer of 2008, hit with declining sales and competition from big box stores, the Nanaimo location closed and the building was shuttered, where it has remained empty to this day.

As one of Nanaimo’s most high-profile properties, located at the central intersection of Commercial Street and Terminal Avenue, continues to fall into a state of disrepair, many residents feel it has become a blight on their beloved downtown core.

And it’s not the only one. Four years ago, a fire swept through the Jean Burns building complex across the street and decimated more than a dozen small businesses, including the well-known ACME restaurant. Though the charred remains have been removed and the site fenced off, it has still not been rebuilt, and is referred to by some locals as simply “the hole.”

In all, these buildings are part of a portfolio of around a dozen prominent empty, under-utilized and sometimes rundown buildings in the downtown core, according to Bill Corsan, Nanaimo’s director of community development.

It’s a situation that one downtown business owner referred to as “embarrassing,” but there may be some hope in recent developments.

Next month, representatives from Vancouver-based Steiner Properties Ltd., who own the old A&B Sound building and many other former locations, plan to meet with city officials to discuss the building and property’s future.

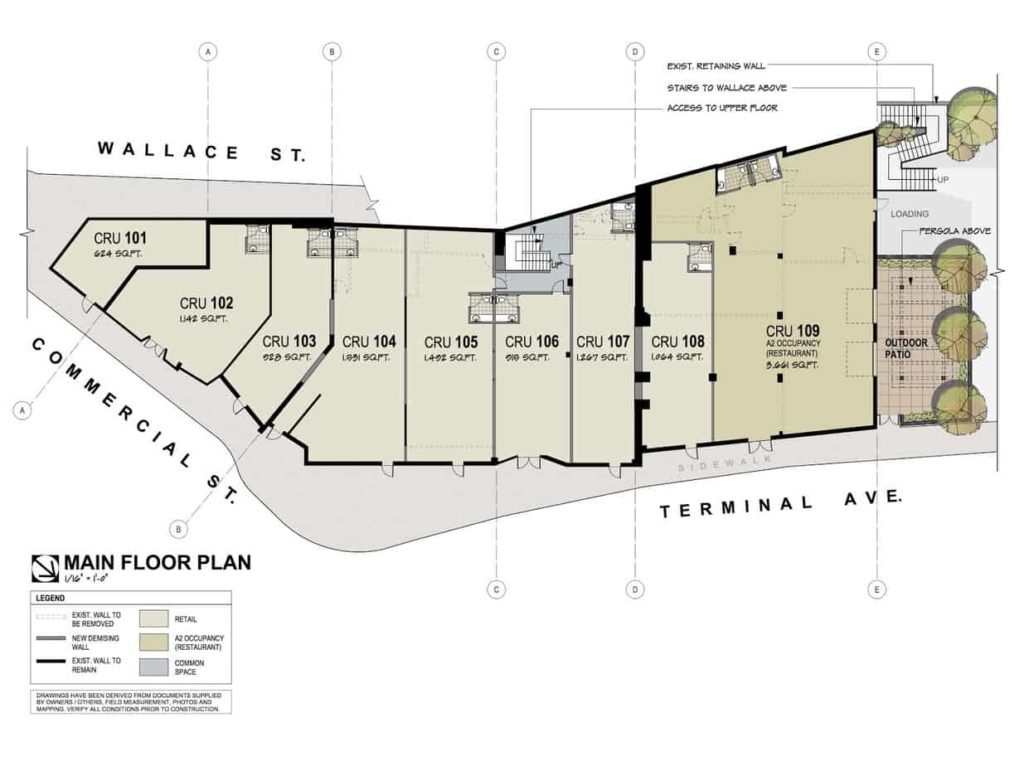

On the table? The company’s finalized development designs looking at potentially turning the property into an enclosed, open-air concept marketplace like Lonsdale Quay Market, Granville Island Public Market, or Fisherman’s Wharf in Seattle, complete with spaces for small businesses like breweries, says Jacob Steiner, head of operations at Steiner Properties.

“We think that would be great for activating Terminal Avenue and trying to slow down what feels like a mini highway in the middle of downtown and turn it into more of a walkable, bikeable area,” says Steiner, whose grandfather is A&B Sound’s founder Fred Steiner.

“Potentially some services up along Wallace where the elevation grade changes, so it’s kind of like a two-story building on the Northwestern plane, you kind of follow the slope upwards and then bring in a set of stairs, possibly down the retaining wall from Wallace.”

What it will take to redevelop

Though plans are still in the development stage, Steiner says the Commercial Street property is the next priority to redevelop after their current project to demolish and then rebuild on another old A&B Sound site near the former PNE grounds on Hastings Street gets closer to completion.

However, there may be a few hurdles to overcome first, says Corsan.

One challenge for many of the properties in the whole area of Terminal Avenue, including the old A&B Sound building, is that it is filled land that was formerly underwater in the 1930s, he says.

“It was all water, it was like Venice. And then all the coal waste got pushed in there, that’s why it’s so flat. So you can imagine there was some kind of a slope going down to the water. There’s pictures of it as an inlet.”

Downtown resident Angela Negrin, who was the last tenant of the property and ran a fish and chip business out of the small end unit in the building, says she remembers going into the basement space under her shop one winter to empty her grease trap and finding it filled with water.

“It was shocking, because it was normally dry and pretty scary and there’s mice and rats down there. And it was like, ocean! Full right up. I was like, where is this water coming from? I was worried it was from me, but there’s no way it could have filled up the whole bottom of the building,” she said with a laugh.

Over time the water went away; her guess was that it had risen when the tide came up.

Negrin, whose family has lived in Nanaimo for four generations, says prior to opening her own Pirate Chips business she worked in A&B Sound’s warranty and customer service department.

Among the largest challenges of building or redeveloping in the Terminal Avenue trench rather than just renovating are the soil remediation and potential geotechnical issues, says Corsan.

In 2014, the Downtown Nanaimo Business Improvement Association was given a Brownie Award by The Canadian Urban Institute for their initiative to get the Ministry of Environment to acknowledge that the fill material in that area all came from one source and at one time, which permitted it to be treated as one block rather than separate properties. This in turn reduced the environmental assessment that was required.

“Those are some of the barriers we’re trying to remove, we’re trying to help all the property owners down there by taking off a lot of the background studies that aren’t really necessary once you understand the overall context,” says Corsan.

“We may have to get creative and just fix up the existing structure as it is,” says Steiner. “Most developers or real estate professionals would say, ‘That’s not ideal, they should knock it down and do some underground parking and then build something fresh,’ but it might not be possible,” he says.

[optin-monster slug=”gsetmbbrfkq8sga6h8wj”]

Across the street, there are similar challenges.

Following a lengthy cleanup and demolition job that site owner Crankshaw Holdings estimates has cost close to a million dollars, the Jean Burns property is now surrounded by a chain-link fence and looks somewhat like an empty concrete swimming pool. Environmental work still continues on the site, and will be followed by geotechnical work and possible rezoning, says Rick Hyne, operating officer for Crankshaw Holdings.

“Everyone points fingers and says ‘You need to do this, and need to do that, and why isn’t this happening?’” he says.

But many don’t understand the variety of challenges the company has faced since the day of the fire, he adds, from insurance and legal issues, to hiring environmental consultants, to the hurdles of negotiating with the city and various government ministries.

In the meantime, whatever the reason, many residents feel exasperated and say they want to see their downtown thrive, and feel that vacant buildings and empty lots are at odds with that goal.

The impact of empty buildings

“Derelict buildings drain cities, downtowns and cores. Downtowns need to be lively, they can’t be boarded up buildings,” says former city councillor Jerry Hong, who runs a popular downtown nightclub called The Queen’s.

In 2018, Hong says he attempted to introduce a derelict building bylaw that would seek to tax rundown buildings at the same rate as better-maintained ones to encourage development or demolition, but didn’t get very far because the city doesn’t have the power under its community charter to implement it.

However, that year council did approve the creation of a downtown revitalization tax exemption program, in which the city agreed to waive their portion of taxes on a property for a 10-year period if developers spend more than $500,000 on a commercial or residential project in the downtown core. The aim is to both encourage new projects and nudge dormant developments, though Corsan says “take up has been slow so far.”

“We only have so many ways of encouraging people to do things with their property,” says Corsan. “This is a common issue, especially in smaller towns. It’s a big issue, vacant properties and how you address them. There are limited tools you can use.”

One thing that can be done, however, is if a property is in disrepair to the point where it is causing a safety concern, the city can then notify the owner to take action, he says. If they don’t, the city can step in to remediate it themselves and then bill them.

This happened at the former Bay Theatre on Chapel Street, for which the city approved a remedial action order in the summer of 2013 to demolish the building after its roof partially collapsed. In 2018, the fire department also ordered Steiner Properties Ltd. to remediate safety hazards at the A&B Sound property after reports of campfires being lit near the building.

A creative solution

In the absence of action around buildings like the old A&B Sound, some residents have taken matters into their own hands.

The 19,000 square foot commercial space sprawls out over three city lots and was originally a grouping of separate businesses before the music giant knocked down the walls and stuccoed over the outside to make it one connected building.

The outside was painted a bright, garish purple to go with the company colour scheme and when the business left, the purple remained. The colour so irked some residents that in 2012 a volunteer group called the Young Professionals of Nanaimo got some grey and brown paint donated and painted the building over to blend in with the neighbourhood until such time that a new tenant for the building was found.

Six years later, people had begun to camp in the alcoves around the building, which was becoming increasingly run down, leading to further complaints from local business owners and community members.

Local artist Lauren Semple said that it was around this time that she was hanging out and looking at the building when her partner Lys Glassford, also an artist, remarked that they’d love to paint the side of the building.

“We started talking about it from there, and started observing it differently. We noticed that people were avoiding it. Community members who were walking down to go to Mambo’s or go to The Vault, to walk up Commercial Street – they would actually change to the other side of the street,” Semple says.

“So that was the plan: if we have to live with this thing, can we turn it into something that benefits the community in the interim?”

After securing permission from the building’s owner, they began to fundraise for paint and supplies as part of their non-profit Humanity in Community collective. After raising $10,000 and conducting a swift artist selection process, the group spent five months covering the building in murals.

Semple says the initiative was never intended as a long-term plan to “save the building” but rather to put the structure to some other use while the community was stuck with it.

Why has it taken so long

Perhaps the wait may soon be over. As for why it has taken so long, Steiner responds that the company is currently working on their ability to lead multiple projects concurrently.

“It’s not like a traditional developer, where you’ve got a massive team of market research and sales people and in-house architects. It’s really just four, five people that every year get the opportunity to work with an outside group of contractors and city planners and take on a project and transform it,” he says.

“We don’t have the traditional background of years and years of construction and then transforming a construction group into a development company.”

Next steps for the project involve investigating practical considerations like asbestos, oil tanks, assessing the roof and other structural issues, and fixing up the outdoor space, says Steiner.

They will also reach out to people in anchor positions within the community to ensure the project goes well, Steiner says.

“We’re doing this once and we’re doing it right. We don’t want to build something that people don’t like and then say, ‘Oh, whoops, we’ll do it better when we learn from that mistake.’ We only have one shot,” says Steiner, who joined the company two months ago.

“We have to do our research up front and get it right the first time. So it takes us a bit longer, but I think we’ll do a better job.” [end]

Editor’s note Dec. 2, 2020: A previous version of this story described the mural initiative as a project of Humanity in Art. In fact is was a project by Humanity in Community. The story has been edited to reflect this.

Want more in-depth local news like this? Get our latest investigations straight to your inbox by signing up for our weekly newsletter.