When it comes to the refugee crisis, there’s a lot journalists could consider doing differently. Newcomers and the people who work with them have told The Discourse that we need more stories about refugees, by refugees. They’re also concerned about the way the issue is framed in the Canadian media.

Mohammed Alsaleh, who came to Canada in 2014 after fleeing persecution in Syria, told me he is concerned that media coverage often ends with the arrival of refugees in Canada. Media portrays it as a happy ending, when people have just begun their lives — and their struggles — in a new country. He’s trying to change perceptions and expand the conversation by sharing his own story, like in this documentary and two TEDx talks (here and here).

My conversation with Mohammed was so good that I want to dedicate my entire newsletter this week to sharing the highlights with you. I’ve edited it for length and clarity.

Alia Dharssi: What do you find valuable about sharing your story?

Mohammed Alsaleh: I consider it my duty to humanize the refugee crisis and bring it to the attention of my new community. A single story like mine can represent the story of millions of people that had their lives changed in the blink of an eye. The second thing is finding meaning. When sharing my story, I have to revisit the most traumatic experiences of my life. To me, finding meaning involves figuring out something good that can come from these traumatic experiences.

When you were studying in Syria, your dream was to be a doctor, but now you’re doing something totally different. Could you tell me more about how your dreams have changed?

I found the best way to deal with immigrating to Canada was to have no expectations. This is a new community, a new society, a new set of systems that you have to navigate. I couldn’t go back to med school because I would have to start from scratch by going back to high school. I also have to support my mom and my five siblings, who are still refugees [living in Turkey and Germany]. So I found a stable job that can fulfill my dreams. My first job was to work in the local refugee welcome centre — the same place that welcomed me to Canada. It made me feel that I was no longer a refugee, but a new Canadian welcoming other refugees. Now, I train private sponsors for refugees.

I wanted to become a doctor to help people and I’m doing the same thing right now, but by different means and different tools. I’m fighting another type of cancer. We live in a world that has 65 million refugees, a record number that haven’t been seen since World War II. This situation is not healthy and I want to change it. That’s why I did a TED Talk focused on changing the perception of refugees.

What is the main way in which you think media coverage of refugees in Canada could be improved?

Before answering the question, I think it’s important to recognize Canadian media are doing a better job of covering the refugee crisis than other countries. But expanding on that, I think the media should do a better job of balancing the perspective of Canada with refugee voices.

Could you share an example of what you mean?

Let’s think about how the refugee crisis was reported before and after the death of little Alan Kurdi. When the free people of the world learned the story of that little boy fleeing persecution in Syria, but sadly drowning in the Mediterranean, everybody finally understood what is happening in Syria, that it’s so bad it will make a family put themselves on a boat where only one person — the father — makes it out alive.

I was a refugee in Canada at the time. Before that, nobody really knew much about our suffering. Any conversation was a struggle. After the days of Alan Kurdi, people could relate to our suffering and started to respond. The newly elected Canadian government invited 25,000 more refugees. The general public privately sponsored thousands of others. That is one small example of how media can change things.

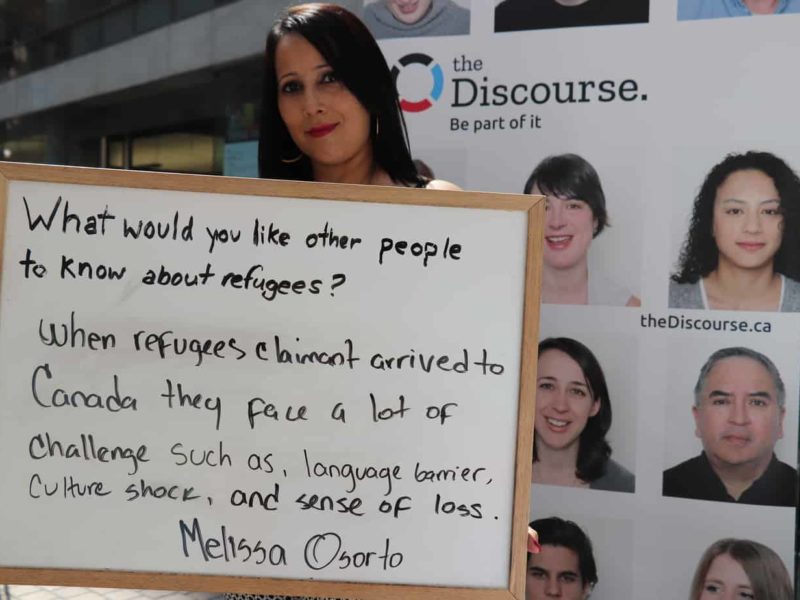

With conversations like the one above in mind, my colleague Francesca Fionda and I are working on telling stories of refugees by refugees. In June, we’ll be hosting two storytelling workshops for refugees in the Greater Vancouver Area. Our goal is to brainstorm how the media can cover refugee issues, especially their experiences settling in Canada, in deeper ways. Email me and let me know if you have any ideas and questions we should consider.

ICYMI: Plastic pollution brief.

Vessels participating in the Volvo Ocean Race discovered plastic at Point Nemo, the most remote part of the ocean. Meanwhile, National Geographic made a splash on social media with its June cover, which depicts a plastic bag that looks like an iceberg floating in the ocean, and launched a “Planet or Plastic?” campaign.

Vessels participating in the Volvo Ocean Race discovered plastic at Point Nemo, the most remote part of the ocean. Meanwhile, National Geographic made a splash on social media with its June cover, which depicts a plastic bag that looks like an iceberg floating in the ocean, and launched a “Planet or Plastic?” campaign.