Just steps away from some of Vancouver’s most recognizable totem poles, a souvenir shop sells cheap knock-offs to unwitting tourists in Stanley Park.

For eight dollars, you can take home a totem pole magnet that says “Made in China” on the back, without any acknowledgement of the Indigenous artists who carved the original poles at nearby Brockton Point.

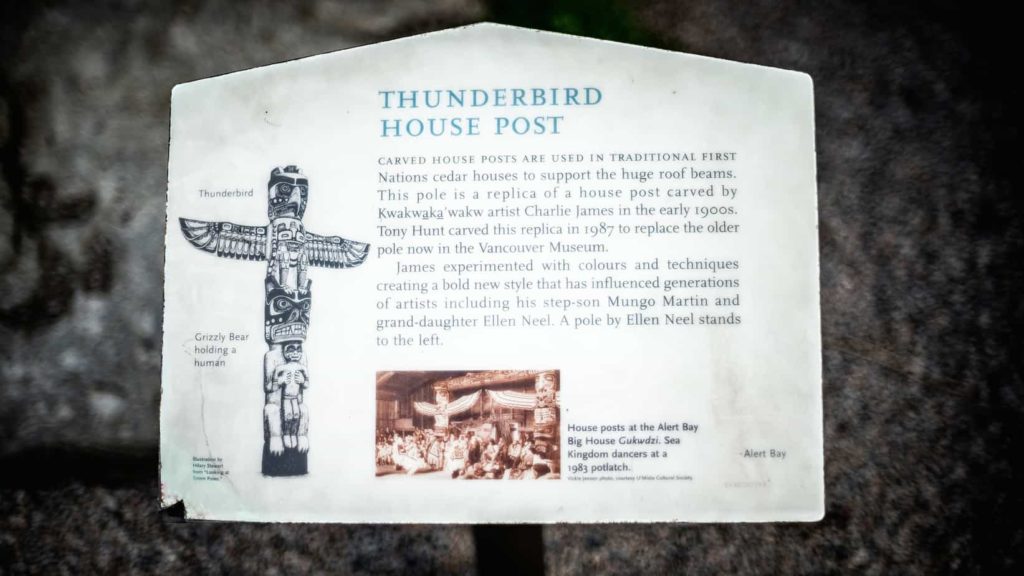

The original poles carry a complex history of the Indigenous nations whose land they sit on, a narrative few tourists will ever hear. The nine totem poles at Brockton Point (most of which were re-carved in the late 1980s after their originals were removed for preservation) were carved by several Indigenous artists, including Charlie James, who created the now-iconic Thunderbird House Post.

Mass-produced replicas of James’s post turned up again and again in Vancouver’s souvenir shops during a recent investigation by The Discourse.

Over the course of five months, we visited 40 tourist shops, examined a sample of their Indigenous-themed wares, asked staff if they could name the products’ artists or nations of origin, catalogued more than 260 items, and traced as many of their origins as we could find. Our conclusion: three quarters of these shops appear to be selling some inauthentic Indigenous pieces, created without any collaboration with Indigenous artists like James or his family.

The repeated appropriation of James’s totem pole comes as no surprise to his great-great-granddaughter, Kwakwaka’wakw artist Lou-ann Neel.

“My grandfather’s totem pole in Stanley Park is one of the most appropriated Indigenous designs anywhere,” she says. “It’s classic, it’s splattered all over. . . with no acknowledgement that that’s his work, which I think is really kind of interesting,” she says. “But, you know, it’s all over mugs and everything.”

Seeing James’ art reproduced leaves Neel with very mixed feelings. She loves seeing people appreciate the art, but it frustrates her to see it done with no acknowledgment, with no understanding of its rich and layered history and the stories that it tells, and with such a disconnection from her family.

“The general public just gets to be conditioned very subliminally around this idea that these are artworks that [are] remnants from a dead culture that’s long past,” she says. They never hear, for example, that some of James’ grandchildren are now carving too, and carrying forward their family’s tradition.

Candace Campo finds this appropriation “problematic, to say the least.”

Campo and her husband own Talasay Tours, which offers walking, hiking and boating tours around Stanley Park, Squamish and the Sunshine Coast, focused on sharing the areas’ Indigenous history and contemporary ways of life. She ends her walking tour of Stanley Park at one of B.C.’s most visited tourist attractions: the Brockton Point totem poles.

A village called Papiyuk existed at modern-day Brockton Point for “millennia,” Campo explains. But the totem poles that were initially put up there by the Vancouver Park Board in the early 1920s were all carved by Indigenous artists from other nations, not the local Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh communities.

These poles did not represent the culture of the local First Nations, Campo says.

Worse, she notes, the inhabitants of the village were displaced from their homes to make room for an “Indian Village” replica that Vancouver’s Art, Historical and Scientific Association wanted to create — but was never completed.

Nearly a century later, Rena Soutar, the first reconciliation planner hired by the Vancouver Park Board in 2017, confirms that the Brockton Point totem poles were brought in by the park board after it decided to replace the existing Indigenous village with an inauthentic reproduction for tourists.

But there’s no signage to tell tourists the real history, and that’s a problem, says Soutar, who is Haida.

“Because at the moment, there’s nothing to indicate the history of this site. There’s nothing to indicate that there were villages here, that people have roots here, that people’s families have lived here for thousands of years before we came along,” she says. “We have none of that narrative in the park.”

As for the gift shop at Brockton Point selling mass-produced replicas of James’s totem pole, Soutar says the park board has nothing to do with that. The shop may be in a park-owned building but its wares are privately selected; the park board doesn’t sanction what the store sells, she says.

Stuart Colquhoun, who owns the Legends of the Moon shop, says up to 80 per cent of his merchandise is Indigenous-themed: many are souvenirs manufactured by non-Indigenous people, while other handmade carvings are produced by Indigenous artists.

“The handmade art is not for everybody. If people want handmade art they would normally go to a gallery,” he says. “We’re in the tourist gift business, and our theme is Native product.”

Colquhoun says his store’s customer base calls for a variety of Indigenous-themed items, from more expensive handmade items to replicas. “You would like to have 100 per cent, and that’s what we’re working towards, but we have a mix of customers,” he says. “If we had all just Native product in here we wouldn’t be… servicing the market.”

For Squamish carver Robert Yelton, that isn’t good enough.

Yelton carved the newest pole at Brockton Point in 2009 as a memorial pole for his mother, Rose Cole Yelton, who was the last surviving member of the Indigenous community that lived in the village there. A decade later he still likes to ride his bike to the park from his home in North Vancouver to share the real history of the poles with tourists.

He says he has approached all three souvenir shops in Stanley Park, including Legends of the Moon, to ask them to stop selling inauthentic souvenirs. He says it frustrates him to see knock-offs on the shelves when there are so many talented Indigenous carvers and artists nearby, some of whom are struggling to make a living from their art.

“The only thing I’m glad about is she does buy carvings off our people, which is good, and she’s one of the only ones that does,” he says, referring to Eleanor, the buyer at Legends of the Moon.

Eleanor, who declined to be interviewed for this article and instead referred all questions to the shop’s owner, Colquhoun, said in a subsequent phone call that she had no recollection of the conversation Yelton says took place. Colquhoun says he’s not aware of any such conversation with Yelton, either. But he would be happy to talk to any artists Yelton suggests, he says.

“It’s a lack of supply,” Colquhoun says. “It’s not an issue that we’re not trying to get First Nations-designed material.”

Yelton says there are many carvers in his and other local Indigenous communities who would likely be happy to sell their work in tourist shops around Vancouver, if given the chance.

“You would have authentic, real carvings, rather than this crap,” he says, “which is carbon copied — they’re all identical, there’s nothing spectacular about them. And not only that, they’re stealing our art,” he adds.

For Lou-ann Neel, one of the lasting problems with the appropriation of her great-great-grandfather’s totem pole is the disconnect between its original meaning capturing and honouring a complex family history — and how it’s now being shared.

“What we need is to show other people who we really are, and where we come from,” she says. “And he was really proud to be able to convey those messages to people.”

“It pains me to see some of the really poor reproductions of it. It’s just troubling to see that,” she says. “And especially when we’ve never really had a chance as a family to respond and say, ‘We think people should talk with the families who have the rights to these images or to these pieces and how they’re meant to be shared.’”

Neel says her great-great-grandfather’s totem pole could potentially be reproduced now in a fair manner on a large scale, but only if her family is in charge of its designs and any profits arising from them.

“Both my grandfather and my grandmother were absolutely for the development of this commercial market, as long as we were in charge of our own designs,” she says. “And that our communities benefited.” [end]

This story is part of a series on fake Indigenous art in the tourism industry. It was edited by Robin Perelle.