Last week, I managed to swing by the opening night of Biometaphysicalmateria, the master of fine arts thesis exhibition of this year’s Emily Carr University of Art + Design MFA degree candidates.

Though there were some stunning artists featured, my main reason for going was to check out What is Sacred, the installation from Eliot White-Hill, Kwulasultun, a local Coast Salish artist and storyteller from Snuneymuxw First Nation who also has roots in Spune’luxutth and Hupač̓asatḥ First Nations.

After he spoke to the crowd on behalf of all the students, I chatted with White-Hill about his foray into sculpture and his thoughts on the revitalization of Coast Salish art.

Here’s an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

Julie Chadwick, The Discourse: I notice you’ve done some three-dimensional pieces here. Have you ever worked with cardboard before?

Eliot White-Hill, Kwulasultun: This is the first time I worked in cardboard. I had these ideas to do sculptural maquettes for a larger-scale sculpture. It’s like a small-scale model, so I was using paper and cardboard. And I was interested in what I was doing, but it didn’t feel totally resolved quite yet. But then I started using pizza boxes from my apartment and [the work] really gained a new life.

This body of work is responding to an archeological dig that took place on Gabriola, where a beetle pendant was dug up. So responding to the forms of the beetle pendant and historical Salish art, but then also talking in dialogue about critiquing anthropology and the way that knowledge was appropriated from Indigenous peoples by anthropologists, and similarly, how Indigenous art forms were appropriated by abstract artists through the 20th century.

It’s playing with those critiques and the absurdity of artifacts as a concept. The pizza boxes are an artifact of my own life. And it’s all tied into my thesis work, which is about the revitalization of Coast Salish art, and thinking about — what does it mean for us as Coast Salish artists today to be making work that is reclaiming knowledge? That is re-telling stories that are deeply sacred to us, but in our own ways?

And we don’t have to be constrained by certain materials or mediums.

Chadwick: Tell me more about the beetle pendant.

White-Hill: Yeah, so this beetle pendant was carved out of coal, which is just profoundly significant for the history of Nanaimo. It’s a very simple and unique instance of Coast Salish art that I really love.

You have a kind of nose, which is where it was pierced through for a lanyard or a necklace, and then the eyes are just circles. There’s a crescent here and on the bottom. It’s so distinctly a beetle, which is really interesting because you don’t see insects represented very often in traditional art. And I really love that because all across my practice, too, I’ve been trying to do work that honors the little beings who aren’t seen that often, like the mosquito.

So often it’s the raven or the eagle. There’s a lot of value to those stories, but I also want to bring out the ones who aren’t seen as often.

Chadwick: What’s the story behind this piece?

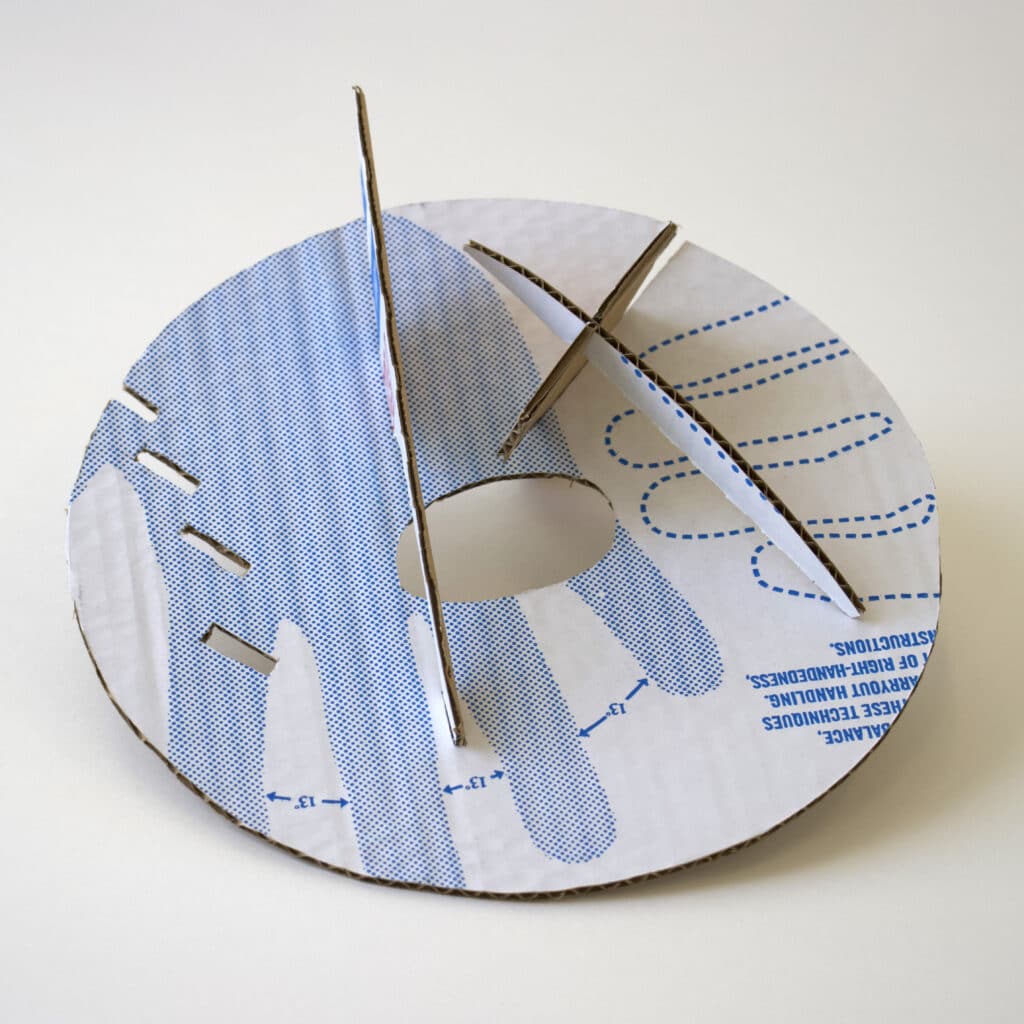

White-Hill: This is an abstract spindle whorl. With all of them, I didn’t look at the pattern, I just cut the cardboard side and then saw what it was. But this one, I flipped it over and it has these hands. They’re [printed] right around the bottom of Domino’s boxes, in a cheeky way. They tell you how to hold your hands, right down to holding them 13 degrees apart with your fingers.

But there’s a spindle whorl from Nanaimo that was taken from our community in 1910 or so and it’s, it’s… almost identical. It was just such a synchronicity.

[White-Hill takes out his phone and shows me a photo of the spindle whorl, with carved hands in an almost identical placement to those on his cardboard carving.]

Chadwick: Wow. I have chills. That’s so crazy. How did you find the original spindle whorl?

White-Hill: I’ve been curating this exhibit for the Nanaimo Museum, it has the same subject as my thesis — the revitalization of Coast Salish art. And I’ve been able to bring this spindle whorl back to Snuneymuxw for the first time in 100 years. It was just sitting in the museum collection.

These are the kind of synchronicities that I try to listen for and open myself to when I work.

Chadwick: Oh my god.

White-Hill: A lot of my work has been centered around a quote from elder Bill White, that Coast Salish art is to make the sacred visible.

I’ve been thinking about that, and unpacking that. What does that mean to me? There’s certain kinds of sacred that aren’t meant for the public. And when we work as Salish artists, we don’t represent that in public.

‘Honouring and celebrating stories’: Emerging Coast Salish artist inspired by community

But there’s a lot of stuff that my great grandmother would talk about, that sacred is all around us. Sacred is every part of our being, and every part of our lives in our existence here. And so what does it mean to make art in light of that? And that’s been the central point of my work here.

There’s a whole other layer of dialogue to this work, where it’s talking about food sovereignty and the ways that commercialism and capitalism have impacted our ways of life. Access to different kinds of food is a lot more difficult in Indigenous communities.

But at the same time, I also love pizza [laughs]. I love Hawaiian pizza from Domino’s and I ate a lot of it during this program. So it’s always different kinds of nuanced layers of narrative, and trying to honor Indigenous ways of life both traditional and modern.

The Emily Carr University of Art + Design MFA Thesis Exhibition runs until April 9. The Nanaimo Museum’s exhibit, stem ‘al’u ‘u’ ni xe’xe: What is Sacred? is guest-curated by Eliot White-Hill, Kwulasultun, opens in May and will run until November.