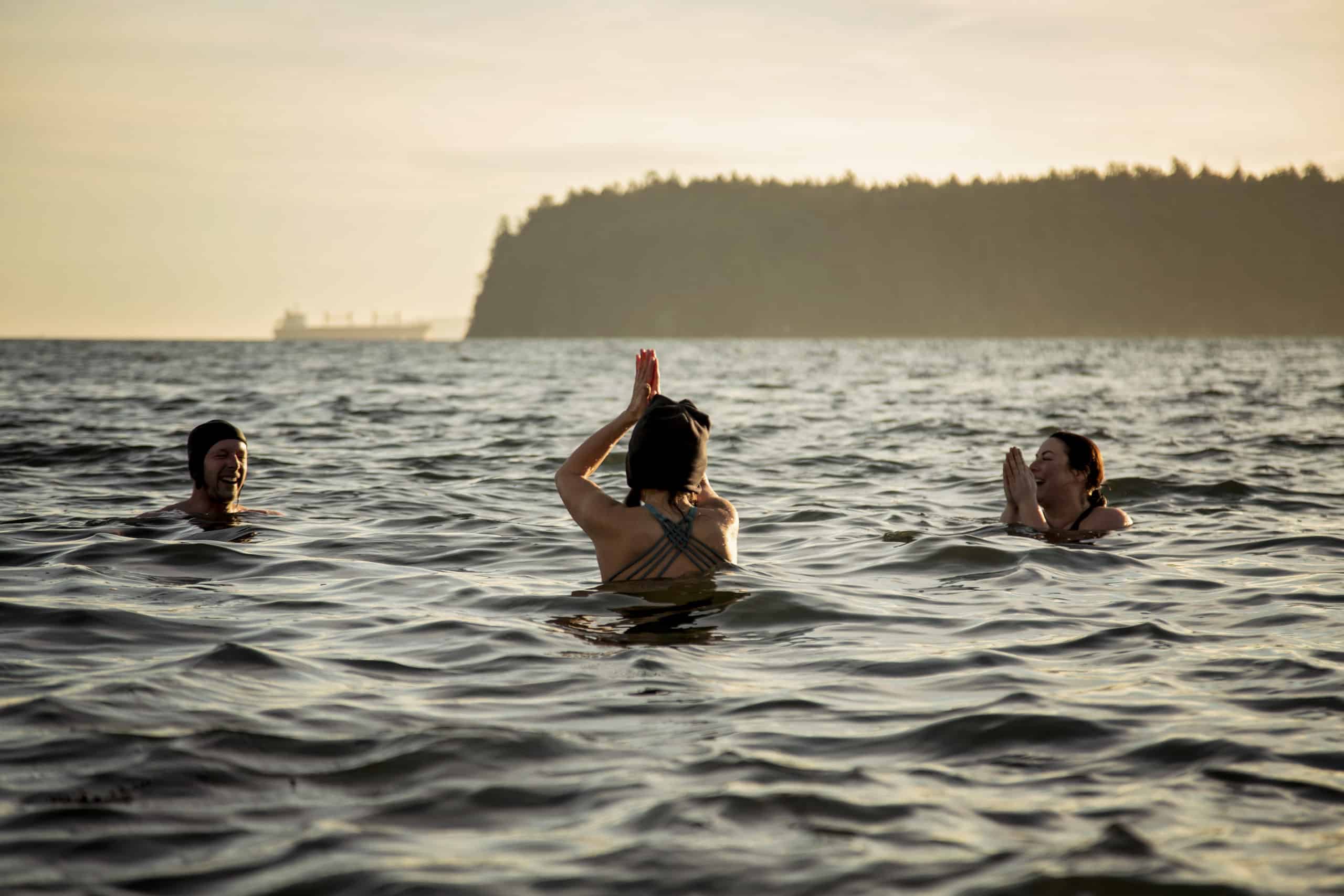

Following the crisp winter breeze, Andrew Pahl starts his water cleansing facing north, and then dunks himself in each four directions before floating in the ocean to sing or chant. It’s a cultural and spiritual practice for him; a journey he has been exploring for the last three years.

“There is the spring equinox, summer solstice, fall equinox, and then the winter solstice. That is when traditionally, as a people, we would do these water cleansings. Each season represents something different. The winter season represents the passing of life,” explains Andrew, of the Gitga’at Nation, Tsimshian Tribe of Raven clan, who is evolving these teachings with knowledge of his ancestors.

“Our people have always practiced getting into the cold; it’s good for you. It conditions your heart. It mitigates depression and anxiety. It helps to strengthen your bones.”

Although a centuries old tradition in many cultures, cold water swimming has only recently gained popularity worldwide. Surrounded by the chilling Pacific Ocean, Vancouver Island is a perfect location to dip into the cold water. In the winter months, average water temperatures range from 5 to 10 degrees Celsius, though surface temperatures can climb to 20 degrees in Departure Bay during the hottest months of summer.

If you frequent the beaches at Departure Bay, you’ve likely noticed the trend. On a cold Sunday in January, people undress to their swimwear, others rush to grab a towel. Some staff members of the emergency team at the Nanaimo Regional General Hospital challenged themselves to take a dip every day for an entire year, and now frequent Departure Bay at 9 a.m. on Sunday mornings.

Before their group, body positive health and fitness coach Gillian Goerzen and her OneCrew Community of adventurous women try to dip at 8 a.m. “Our intention is to be here at sunrise for a dip in the ocean. There’s something magical about sunrise, right?” says Gillian.

Cold water swimming to kickstart the brain

Like many cold water converts, Gillian dips in the water because of the mental health benefits the practice can create. She has personally noticed an improvement with seasonal depression.

For most, it may seem crazy to shock the body in freezing cold water, but the counterintuitive ways in which it benefits the body and mind is truly fascinating.

As soon as the body is exposed to cold water, the nervous system kicks into the fight-or-flight response: the heart beats faster, blood pressure skyrockets, adrenaline is released into the bloodstream and the brain receives a boost of oxygen and beta-endorphin hormones. These endorphins likely explain why most swimmers say they feel good and energized for the rest of their day.

Mike Tipton, an environmental physiologist at the University of Portsmouth’s Extreme Environments Laboratory, explains in BBC Science Focus Magazine that it only takes six immersions to adapt your body to the shock response. This ability to adapt to stress in the water over time can cross over to daily life, and make a huge impact on a person’s overall well-being by building resiliency.

“What you’re essentially training yourself to do is work through fear, because your body will accept the cold with open arms, but your mind won’t,” says Andrew, who has noticed a drastic decline with depression since starting his practice. “So one needs to be at a certain point in their life where they’re able to be still in the face of animosity.”

“The first four minutes are really hard,” says Diane McGonigle, who swims with two different groups at Piper’s Lagoon and Departure Bay. “Your body is tingling, but if you can get yourself past that, your body sort of goes into a different mode. It’s amazing to know that you can work with your body to do hard things.”

She’s been able to train her body to stay in the cold water for 20 minutes, and says focusing on your breath is key to a positive experience.

The Wim Hof Method, a renowned methodology for cold water immersion, has helped popularize the practice. Founder Wim Hof, known as the “Iceman,” has been featured in countless documentaries and podcasts for his ability to endure frigid temperatures and belief that everyone can benefit.

Consistent exposure to cold water among people in good health has been shown to act as a natural antidepressant, reduce inflammation in the joints, improve cardiovascular circulation and more.

Cold water exposure can be practiced in a lot of creative ways from ocean dipping to ice baths or cold water showers at home. The purpose of each method the remains same: connect the body and mind to build resiliency.

Swimming through COVID times

The practice seems to be gaining popularity on the island, not just for its significant medical benefits, but it is also one of the few pastimes not restricted by COVID regulations.

“I’ve really missed people during COVID, so just getting together outside and doing something kind of crazy and silly makes you feel great for the rest of the day,” says Erin McPherson, one of the swimmers with the OneCrew community.

“It’s having this deep connection with nature as well,” says Andrew. “Through all of this, it’s really good to get to know oneself and grow through this.”

For those looking to take the plunge, Gillian recommends that swimmers go with other people and stay focused on how their body is reacting.

“You have to make sure that you’re listening to those cues and what early hypothermia looks like, so you get out early enough,” she says. “Your body will continue to chill after you get out of the water.” Early signs of hypothermia include slurred speech, drowsiness and confusion.

Going into the ocean with water shoes, gloves and a warm hat can help. Having a warm towel and clothes close by shore are also good preventative measures to take.

Erin, who came out to her second swim this afternoon, highly recommends doing a few dips before giving up or giving in to the hobby.

“The first time was awful and extraordinary all at the same time. I had a really hard time focusing on my breath,” she says, and spent a year contemplating participating before taking the plunge. “I think it has to be your decision. You have to want to do it for yourself.” [end]