Kelly Black, PhD, is a researcher, writer, historian, and collector of books. He has taught B.C. and Canadian history at Vancouver Island University, and is the executive director of Point Ellice House Museum and Gardens in Victoria.

Travelling down a rural road in the Cowichan Valley can be an exercise in adventure — filled with twists, turns, and narrow lanes. Visitors may be surprised to find a lack of straight roads such as those found in the prairie provinces and parts of the Lower Mainland.

In fact, a reader of The Discourse shared this question: “I am curious to know why the Cowichan Valley was not settled according to a grid system. I ride a motorcycle and love the winding roads. Who doesn’t? I was born in Aldergrove in the Fraser Valley — also rolling countryside, but where the grid system does prevail. Which makes me wonder.”

As a local historian, I’ve researched the story of settlement in the Cowichan region. And while many of these winding roads are today a hallmark of Cowichan’s pastoral charm, their routes can be traced to the processes of colonization which transformed lands of the Cowichan Tribes, Halalt, Lyackson, Ts’uubaa-asatx, Penelakut, and Malahat peoples into an agricultural settlement. These roads do more than get us from Point A to Point B. They tell a story about the particular way that colonization occurred in the Cowichan Valley.

The search for arable land

As early as 1852, the Hudson’s Bay Company identified the agricultural potential of the Cowichan Valley. In correspondence to London, HBC Chief Factor James Douglas wrote: “[The Cowichan First Nations] were extremely friendly and hospitable to our party, and gave us much information in regard to the interior of the country; which by their report appears to be well watered, and abounding in extensive tracts of arable land.” He goes on to describe the crops that were “flourishing” on the land, like potatoes and cucumbers.

Following the Fraser River gold rush of 1858, a large influx of people to Victoria cast new eyes on the valley’s agricultural potential. However, as the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group notes, “The Hul’qumi’num people were historically renowned as a people who vigorously asserted control over our lands and resources.”

Despite a number of violent incursions by Douglas and the Royal Navy, offers of purchase were rebuffed by First Nations. Still, the colonial government went ahead and surveyed the valley for settlement in 1859.

An article in the academic journal “BC Studies” by Darby James Cameron argues that colonial authorities “… used surveyors to construct knowledge of the land that fit their own geographical worldview before settlement and resource exploitation began.”

The surveyors

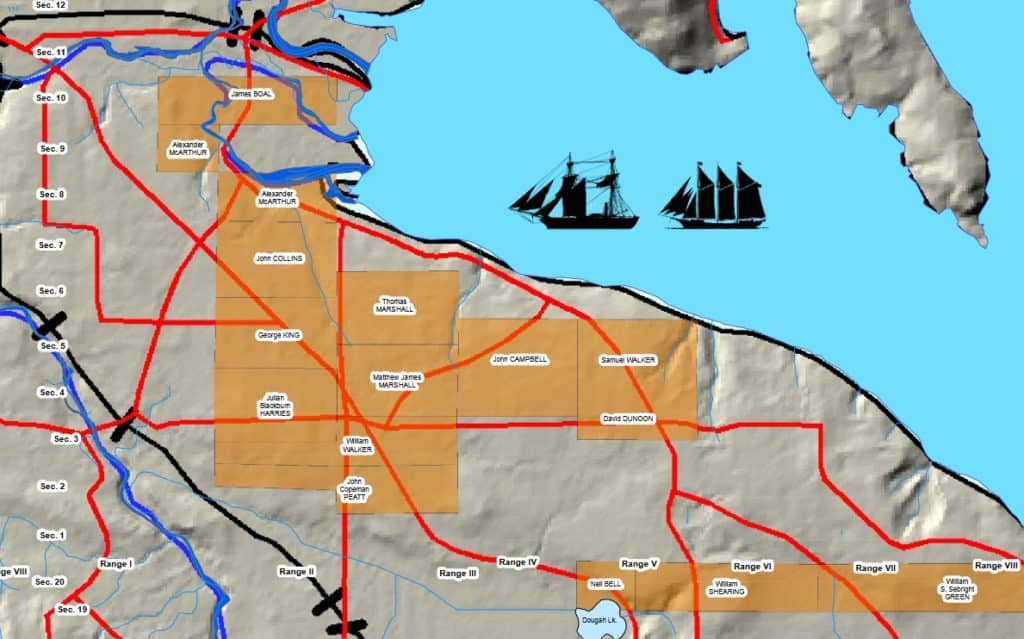

Joseph D. Pemberton was appointed Surveyor General for Vancouver Island in 1859 and one of his first tasks was to survey lands north of Victoria. From March to May 1859, Pemberton’s assistant Oliver Wells laid out five districts in Hul’qumi’num territories — they were labelled Cowichan, Shawnigan, Somenos, Comiaken, Quamichan and Chemainus. Maps from this survey — and those that followed to correct and hone Wells’ work — show a system of parcels intended for land hungry settlers.

With land divided into ranges and sections, the survey was an essential step in the process of colonial dispossession. During the surveyor’s work, important natural resources, potential farm land, and settlement areas were noted and delineated. Maps, land registry offices, settlers and, eventually, roads followed.

The Cobble Hill Historical Society and researcher Jim Ward have published a number of maps which show where colonial surveyors divided the land into rectangular parcels. These maps are currently on display at the Cowichan Valley Museum and Archives in Duncan until the end of June, 2022. Ward’s maps also label these parcels with the names of early settlers who took up their “pre-emption” (the right to purchase land at a set price and under certain conditions), many of them arriving onboard HMSHecate in August 1862.

Surveyors, maps and gunboats allowed these settlers to take land without much regard for the opposition of First Nations. Since there were few roads at this time, surveyors accompanied these would-be farmers to their parcels of land in North and South Cowichan.

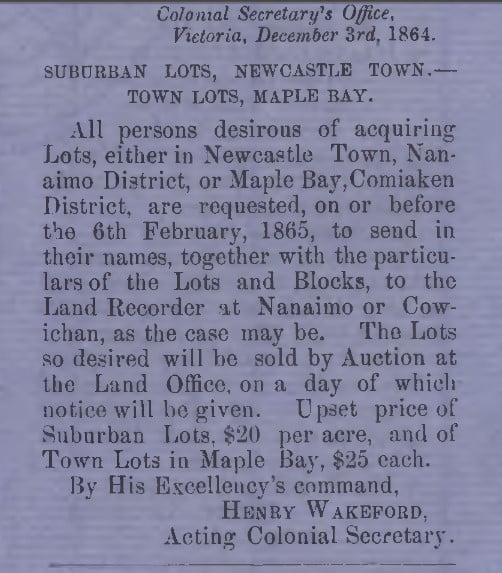

Close examination of a map of the Cowichan Valley reveals a few places where there are straight roads laid out according to a grid system (the division of land into equal parcels with corresponding roads and lots). The Maple Bay townsite, for example, was set out in this way by surveyor John McGill Otty in 1864.

Harrisville, now called Cowichan Bay, was also established on a grid system with blocks, small lots and road allowances in 1873, though looking at a map online shows that this effort to create a townsite did not pan out as envisioned by Otty. Mostly, it’s the roads in between these townsites that hold the twists and turns familiar to anyone who ventures off the Trans-Canada Highway.

Cutting a road

An excerpt from The Warm Land: A History of Cowichan by Elizabeth Blanche Norcross gives some insight into the difficulties of establishing roads in Cowichan. The geography of the place, combined with a lack of resources (both human and financial), led to many early roads being practical and expedient rather than straight and wide.

“‘Cutting a road through’ in Cowichan was no figure of speech,” the book says. “It involved felling sizable trees almost every yard of the way, even though the early road builders went around, rather than through the largest trees.”

In other places, First Nations trails and early paths established by settlers eventually became roads. These informal paths and their conversion to wagon roads sometimes created conflict between settlers, especially in places where more precise surveys were not complete. In 1898, John Nightingale wrote to Premier Turner asking that he stop James Dougan’s proposed road from Cobble Hill to Cowichan Bay from “laying waste” to farmland and fencing.

Where and how a road should be built also generated debate. The BC Archives in Victoria holds many letters written to colonial and provincial officials regarding support for, and objection to, the proposed routes. Perhaps most well known is the debate over construction of a Malahat Route, which occupied settler meetings and petitions for many decades before it was finally completed in 1911.

Whether straight or winding, roads connect people and places — but they also connect us to the past. Roads were essential to the establishment of a settler society that intended to dispossess First Nations from their territories. Before the arrival of settlers and roads, however, the colonial government created a framework for settlement using gunboats, surveyors and maps.

Straight roads and city blocks based on the grid system survey can be found in certain towns throughout the Cowichan Valley, but the routes with the most twists and turns are often connected to the particularities of Cowichan’s local geography and history. [end]