This article contains stories of abuse endured by people at residential “schools” and the Nanaimo “Indian Hospital” that may be triggering. Support for Indigenous survivors and their families is available. The KUU-US Crisis Line Society offers 24-7 support at 250-723-4050 for adults, 250-723-2040 for youth, or toll free at 1-800-588-8717.

Snuneymuxw First Nation received a contribution of $77,250 on Sept. 15 towards their efforts to search for unmarked graves on the former grounds of the Nanaimo “Indian Hospital.”

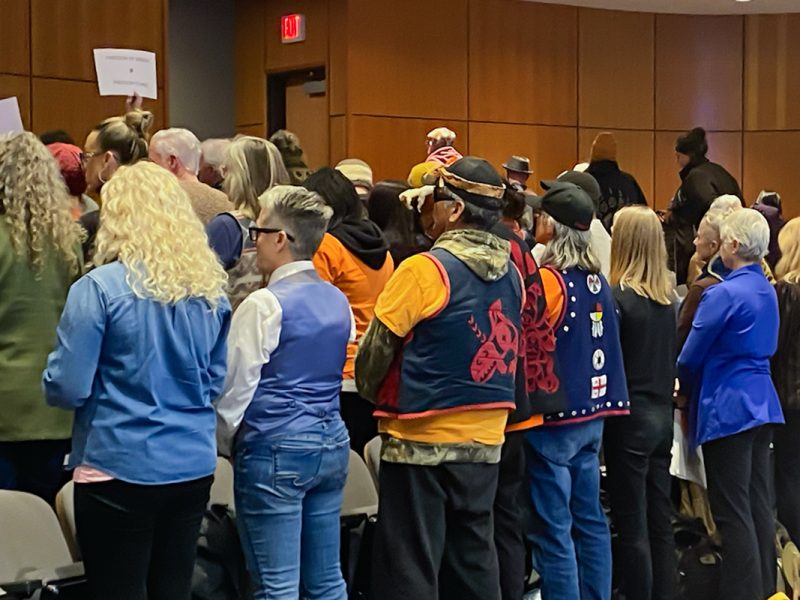

The crowd-sourced funds were presented by KAtēwha‡et (Tom) LaFortune, a carver from SȾAUTW̱ (Tsawout) First Nation, and filmmaker Steve Sxwithul’txw, a residential school survivor from Spune’luxutth (Penelakut Tribe), in an emotional ceremony in the chief and council’s chambers.

Together with Kwakwaka’wakw cultural safety educator Michele Mundy from the ‘Na̱mǥis First Nation, the two said they decided to organize a GoFundMe fundraiser after hearing the confirmation from Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation that they had located the remains of 215 children buried in unmarked graves on the former residential school grounds in Kamloops.

“When it first hit the media about the 215 children in Kamloops, when it finally started to become common knowledge, where it can’t be ignored anymore, I sat in the carving tent and I couldn’t think. I couldn’t move forward. All those little lost souls that were taken. Very small. Away from their families, no idea where they were when they left this world. It was important to me, to help find these children and bring those lost souls home,” says LaFortune.

“This is part of healing for the younger generations coming up, to teach them what the Elders and our ancestors have gone through their whole lives. This is a time for teaching all of us.”

Chief Xumtilum (Michael) Wyse echoed this point as he addressed the room filled with Elders and survivors of both the so-called Nanaimo “Indian Hospital” and the residential “school” systems.

“We’re gathered here today to acknowledge in a public way, our ancestors who have suffered a great deal, and the intergenerational trauma that our people carry,” says Wyse.

“Our people were treated as less than human, as medical experiments, and disposed of without regard to the sacredness of human life and deposited into unmarked graves in our territory. These are the stories, an enormous physical, emotional and spiritual pain, that has been passed down through the generations and carried forward today by our Snuneymuxw people. At this time we must bring forward all resources to support the healing of our people.”

Though the original goal of the fundraiser was just $25,000, a total of $157,050 was raised “from Canadians, from people on the Island, from non-Indigenous people across North America who sent us heartfelt messages of anger, of love, of support,” says Sxwithul’txw, who added that people were “aghast at how this could happen in their backyard and most non-Indigenous people knew nothing about it.”

The other portion of the funds went to Ahousaht First Nation in July to support ground-penetrating radar searches at two residential “school” sites near Tofino, the Ahousaht Indian Residential “school” and the Christie Roman Catholic “school.” Chief Greg Louis told CTV News that the crowd-sourced funds “will allow the nation to get started regardless of the response from the federal government.”

The resources presented to Snuneymuxw First Nation will go towards both on-site investigations and the search of historical records, which are notoriously difficult to access, as well as funding ground-penetrating radar equipment, says Wyse.

In addition to the so-called hospital site, there are approximately 60 unmarked graves in the on-reserve cemetery that also need investigating.

The nation is also in talks with Telus regarding a vacant lot on the site of their current housing development on Wallace Street. It was formerly the site of St. Ann’s Convent and Academy where they ran an orphanage, Wyse says, and they believe there could be unmarked graves there as well.

“Our intention is to allow this work to guide us. We’re not going to predetermine findings or results of the investigative works. Updates will be provided as we move forward, together. Moving with one heart and one mind when dealing with this kind of cultural and spiritual work is important to Snuneymuxw,” says Wyse.

The Nanaimo “Indian Hospital” was located across from what is now Vancouver Island University and operated from 1946 to 1967. It was one of 29 across the country and saw more than 14,000 patients from all over Vancouver Island.

According to historian Maureen Lux, these segregated hospitals “emerged from deep anxieties about Aboriginal people and their perceived threat to the public’s health” and not out of concern for the health of Indigenous people. Many Indigenous people were forcibly confined; the Indian Act was amended in the 1950s to criminalize Indigenous people who refused to go to the hospital or leave before being discharged.

Many survivors say they were sexually and physically abused, tied and shackled to beds sometimes for years and subjected to sterilizations and medical experimentation against their will. Because the Canadian government refused to return those who died at the so-called “hospitals” to their communities unless their relatives paid the costs, many were buried in unmarked graves.

Laurie Meijer Drees, professor at VIU’s Indigenous/Xwulmuxw Studies Department, has spent decades compiling oral histories from survivors of these “hospitals.” She stresses the importance of moving “beyond routine colonial interpretations of victimization, oppression, and cultural destruction” to understand how survivors drew from Indigenous healing traditions and bonds with one another to overcome abuse.

At the Sept. 15 event, Elders supported one another as they shared some of their experiences at the “hospital,” which included childhood accounts of having entire sets of teeth forcibly removed without anaesthetic and being tied down and force-fed alcohol.

Elder Earl Manson says he was about five or six years old when he was sent to the so-called Nanaimo “Indian Hospital” in 1951. He had broken his arm, but doesn’t understand why he was then forced to stay there for months.

“I remember running around under the beds. They were so high. And getting strapped into my bed. I was so small I could get away from them chasing me, they were chasing around trying to catch me. There’s black memories,” he says, his voice shaking. “It opens some doors for me right now. It clicks in, when [other survivors] talked about a high bed. It clicked in. I remember running around under the beds, trying to get away.”

Earl says he wants access to the hospital records so he can understand more about what happened to him and others who were sent there.

“It’s very hard to go back there. I am a survivor of residential school, and as soon as I heard those stories about finding those bodies, it triggered the face of my abuser, instantly,” said Earl’s brother, Elder Xulsimalt (Gary) Manson.

Xulsimalt described the years of pain, addiction and institutionalization that haunted his life after he escaped from the school and how that passed down through his family. After living in denial about the atrocities he had suffered there, he says that he eventually learned to face it.

“I did a lot of crying for a long long time after that. I feel the fear in here right now. What we might find there. So I’m glad all the Elders are in this room right now to hold each other up.”

Xulsimalt says he is relieved that the public is finally paying attention. “I’m grateful, very grateful, that you’re doing the work that you’re doing because we run out of energy to deal with this all the time. We deal with it constantly. Our leadership deals with it constantly. Every time somebody builds a building or something, we’re reminded of what suppression has done to our people. And as long as I have a memory, that will never go away, that history will never go away.”

In June, the province announced a $12 million fund to go towards searches at residential school sites all over B.C. in addition to cultural and wellness support services. The federal government announced its own financial commitment of approximately $320 million in August.

But many survivors say this is just scratching the surface, as churches and the Canadian government have withheld or destroyed records that are essential to the search, recovery and commemoration of those who were taken.

“It’s hard because no one is taking responsibility for what’s going on or how it’s going on,” says carver, Tsawout member and intergenerational survivor Perry LaFortune, who was also present at the ceremony.

“The government are ultimately responsible, the churches, the military, the police, everybody. One of the things that came to mind when this really started taking off was that this is an awakening. Our young people are being found now, some of them don’t know that they’re gone. They’re going to be brought home.” [end]

Support for Indigenous survivors and their families is available. The KUU-US Crisis Line Society offers 24-7 support at 250-723-4050 for adults, 250-723-2040 for youth, or toll-free at 1-800-588-8717. For anyone that feels distressed by this information, here are some suggestions for self care

In 2018, former patients of “Indian hospitals” filed a class-action lawsuit against the federal government. If you believe you may be a class member, please call 1-866-777-6308 or contact indianhospitalsclassaction@kmlaw.ca for more information.