Greater Victoria community members and conservation groups had a big reason to celebrate at the end of 2021. After a year of campaigning and working together, a rare and beloved piece of land known as Mountain Road Forest came under the indefinite protection of the Capital Regional District and a local organization called Habitat Acquisition Trust.

It took $3.4 million, advocacy, community partnerships and intense effort to save Mountain Road Forest — a 50-acre (20-hectare) property, located near Prospect Lake. That’s about a quarter the size of Victoria’s Beacon Hill Park. But to the people who treasured the land, the hard work and expense was worth it.

The parcel, not far from the bustle of urban life, had been owned by the same family since 1971. They graciously allowed neighbours to enjoy it for quiet use. It is home to cliffs and rock outcrops, endangered Coastal Douglas-fir and Garry Oak meadow ecosystems, and a spring-fed stream that is part of the headwaters of the Colquitz River system. Locals came to appreciate the property and saw themselves as its stewards.

“Thank goodness there are so many people who care,” says Katie Blake, executive director of Habitat Acquisition Trust, an organization that works with partners towards conserving land in Greater Victoria.

When the property was listed for sale, a group organized as “Friends of Mountain Road Forest,” to save it. More than 1,400 community donors stepped up — some with five-figure donations — to raise $1.4 million, Blake says. The Capital Regional District’s Land Acquisition Fund chipped in $2 million, and the landowners donated the balance of the purchase price, in exchange for tax benefits.

“[The landowners] were willing and inspired to do so because of the outpouring of generosity from the community,” Blake says.

This is how conservation is often done on southeastern Vancouver Island, where land is heavily privatised and the remaining forested parcels become increasingly valuable as they are eyed for potential development.

“It takes a community and partnership approach to accomplish what needs to be done and now, we’re really looking at some of the last forested parcels left for conservation,” Blake says. The resources it takes to save what is left can be enormous.

“Really, it does take a lot of stars aligning for things to go well,” Blake says.

Ultimately, she and other experts say broad, large-scale systemic changes are needed to bolster conservation efforts and make a real difference.

Stolen land, endangered landscapes

The lands that cover what is now called the Capital Regional District span the territory of many First Nations, including Lək̓ʷəŋən (Songhees), Xwsepsum (Esquimalt); W̱SÁNEĆ Nations: W̱JOȽEȽP (Tsartlip), BOḰEĆEN (Pauquachin), SȾÁUTW̱ (Tsawout) and W̱SIKEM (Tseycum); Sc’ianew (Beecher Bay), T’Sou-ke, Pacheedaht, MÁLEXEȽ (Malahat) and Pune’laxutth’ (Penelekut). The people from these nations have been stewards and caretakers of these territories, forests and waterways for many thousands of years.

Two centuries of colonial and genocidal policies in so-called British Columbia have worked to separate Indigenous peoples from their land, and this is especially true in Greater Victoria, which is among the most heavily privatized, urbanized and environmentally degraded areas of the province.

The colonial government used what are now known as the Douglas Treaties as one of its tools for Indigenous dispossessions. The story of those treaties and what was agreed to is complicated. However, Indigenous groups descended from those that signed the treaties maintain that no sale of land or relinquishment of title was agreed to. Furthermore, the promises made by the colonial government in those agreements have not been upheld.

Related story: ‘An unlawful act’: Tl’ul’thut (Robert) Morales on Vancouver Island’s E&N land grant

In the years since, nearly all of what’s now the Capital Regional District has been partitioned off and sold as private land holdings. This has led to significant environmental degradation, too.

Greater Victoria is part of the rarest and most endangered zone in B.C., home to more species at risk than elsewhere in the province.

Because of the history of privatization, conservation of what’s left often depends on the cooperation, patience and generosity of landowners. As land values soar, incentives for property owners to keep forests intact shrink. And the costs of conservation rise in step.

Citizen conservation power

But the privatization of land also means conservationists don’t need to rely on the government for help when it comes to protecting it. This makes space for powerful and direct community action.

“If you can raise the money, you can protect the land and take action without the government,” says South Island resident Vicky Husband.

Husband is a member of the Order of Canada and of B.C. and is known for her great efforts to defend nature. She has served as chair of the Sierra Club of B.C. and played a large role in conservation efforts in Clayoquot Sound, Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, the Carmanah Valley and the Khutzeymateen Grizzly Bear Sanctuary.

Despite the difficulties, Husband maintains that citizen advocacy is essential when it comes to conservation and she notes that with private land, it really comes down to working together to raise funds and purchase it for conservation purposes.

Community members working together can make a big difference, and the District of Highlands is proof of that, Husband says. That municipality, located so close to Victoria’s urban sprawl, set conservation as a clear intention when it incorporated in 1993. Many conservation successes in the Highlands have since followed.

Related story: The Highlanders: A community unites against urban incursion

The 2008 acquisition of a 63-hectare parcel of land in the Highlands called the “Kinghorn property” was “a quiet success,” according to a newsletter from the Land Conservancy of BC. It was purchased with conservation in mind and led to the conservation of other parcels as well.

“It’s easy to feel helpless when you see your community being ravaged by development. But when even just a few neighbours band together to make a better tomorrow, great things can happen,” the newsletter reads.

Local residents came together with The Land Conservancy to extend an existing green buffer in the district. Through their work, they were able to acquire several properties — like Second Lake, the Kinghorn property and more in the north Highlands — which make up more than 260 hectares of land, according to the newsletter.

Community advocacy can complicate conservation efforts

While citizen-led conservation efforts can be incredibly powerful, there can also be downsides.

Public interest can drive up the price of land and push sellers to put it on the market for a quick, easy sale. This can conflict with the lengthy, resource-intensive and quiet process that organizations like the Habitat Acquisition Trust engage in.

For example, the listing price for 101-acre forested parcel on Finlayson Arm Road in Langford jumped by 31 per cent to $5.5 million in 2021 after local residents mounted a campaign to try and purchase the property, dubbed “Magical Mountain,” for conservation.

Related story: Langford group launches effort to preserve forested 101-acre parcel of land along Saanich Inlet

Time is crucial to acquisition agencies, Blake says, because it allows for space to gather resources and funding. That means ideally, the agency is also working with a landowner who is willing to wait before putting their parcel on the market. If a property goes up for sale, that means the acquisition agency may have to compete with other potential buyers to acquire it.

“Once the land is on the market it makes it challenging to have that time to campaign and pool resources,” Blake says. “We really do try to get ahead of the for sale signs.”

In the case of the Mountain Road Forest campaign, Blake says the landowners wanted to see a conservation outcome so they were happy to provide the Habitat Acquisition Trust with time and an extension to get necessary resources for the acquisition.

For the land acquisition process to be successful, other factors often have to be in place, too, Blake says.

In order to encourage partners to step up and financially support an acquisition, Blake says the land has to have special characteristics like conservation value (such as endangered species and important ecosystems) and recreation opportunities.

And, in an ideal scenario, Blake says the landowners themselves should be willing to partner with the acquisition agency on the sale. Incentives, including the Ecological Gifts Program, offer landowners tax benefits if they donate land, or a partial interest in land, to a qualified recipient that will ensure it is conserved in perpetuity. The owners of Mountain Road Forest made use of this program to contribute to the campaign.

There are many moving parts when it comes to land acquisition, Blake says, and the public usually isn’t brought into the process until the majority of funding and resources to purchase a parcel of land are secured.

Small victories

In describing the land acquisitions in the District of Highlands, Husband says it’s a process of “picking up pieces as you go along.” But it’s not enough.

“As citizens, we can never protect all of what should be protected,” she says.

And South Island communities can’t bank on much support for federal money geared at increasing protected areas. Last year, Canada made a goal to conserve at least 30 per cent of land and water in the country by 2030.

It’s a big goal, one that makes it all the more likely that the government will focus on protecting large tracts of land, says Blake. On the South Island, the parcels are relatively small and expensive, and likely to be overlooked, despite their significant ecological importance.

“It’s less compelling to put a lot of money towards something where you can’t get a lot of land,” Blake says.

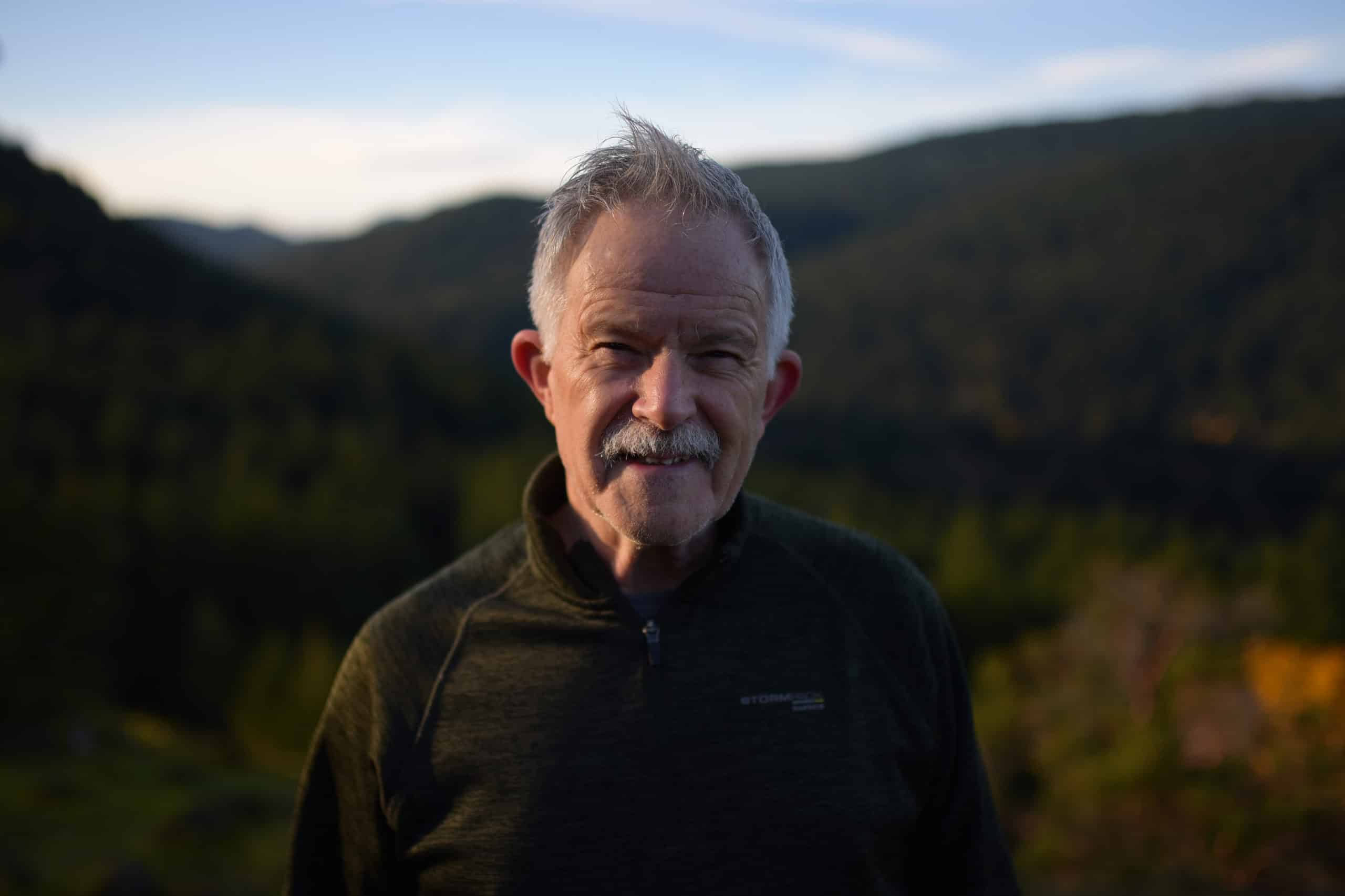

Until the political system changes, even big conservation wins are still just “small victories,” says Richard Habgood, a former director of the Sierra Club of B.C. and veteran environmental campaigner.

“I’m very cynical and the root issues aren’t being solved as long as big money is in control,” he says. “Conservation doesn’t change the system. Big money and government gives us these small victories but not any big ones.”

Systemic change is needed

Habgood suggests that in order to have true conservation in the province, a top-down overhaul of systems — from how we vote to who sits at the decision making table — is needed. For Habgood, that means changing our voting system to a proportional representation system in order to offer opportunities for a diversity of voices and viewpoints in top levels of government.

In a proportional representation system, the percentage of seats a party has in the legislature is a reflection of the percentage of people who voted for the party. In our current First Past The Post system, a party can have a majority of the seats in the legislature even without a majority of the vote.

“You have to have broad-scale change in order to protect conservation efforts and then they won’t be in vain,” Habgood says. “But as the system is right now, that’s not going to happen.”

He suggests that a good place to start when thinking about more impactful conservation is to consider how it is impacted by political processes. He says besides that, it’s tough for citizens to do much more than what they’ve been doing for years.

“I used to be a flaming environmentalist; I still am. But I just kept on hitting this brick wall,” Habgood says. “Me and so many others have put so much money, energy and all the rest of it into conservation and we keep on hitting these brick walls.”

Landowners need much stronger incentives to encourage conservation, Blake says. She suggests offering more property tax breaks for people to protect portions of their properties and discourage them from subdividing and selling or logging them. Municipal governments must be encouraged to make these policy changes, she adds.

Most importantly, though, Blake says anyone working in conservation needs to work with Indigenous communities to facilitate land-based reconciliation. She points to an invigorated push towards creating Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the conservation sector, where Indigenous governments have the primary role in creating management plans, governance structures, objectives and boundaries.

“Reconciliation and Indigenous land sovereignty and stewardship need to be part of conservation,” Blake says.

Habgood agreed that any decision-making about land needs to put First Nations at the forefront.

“This was stolen,” he says. “And it’s really the justice department in B.C. that’s responsible for giving the property back.” [end]

This article is part of the Forests for the Future solutions series, a partnership between The Discourse and IndigiNews.