On Nov. 2 the B.C. government announced its intention to work with First Nations to defer 2.6 million hectares of old growth forest from harvesting.

The recommended deferrals were identified by an independent panel of experts, and focus on the most at-risk ecosystems: big-tree old growth, ancient old growth and rare types of old growth.

The scientists estimate that B.C. once held about 25 million hectares of old growth forest, of which 11.1 million hectares remains. Of that, 5 million hectares is unprotected and at risk, meaning that it is both valuable and available to forest companies. The panel identified just more than half of that (2.6 million hectares) as the most at risk and the highest priority for immediate deferral.

The government has given First Nations 30 days to accept the deferrals on their territories or ask for further consultation. If accepted, no harvest would be allowed for two years as consultation continues towards possible permanent protection.

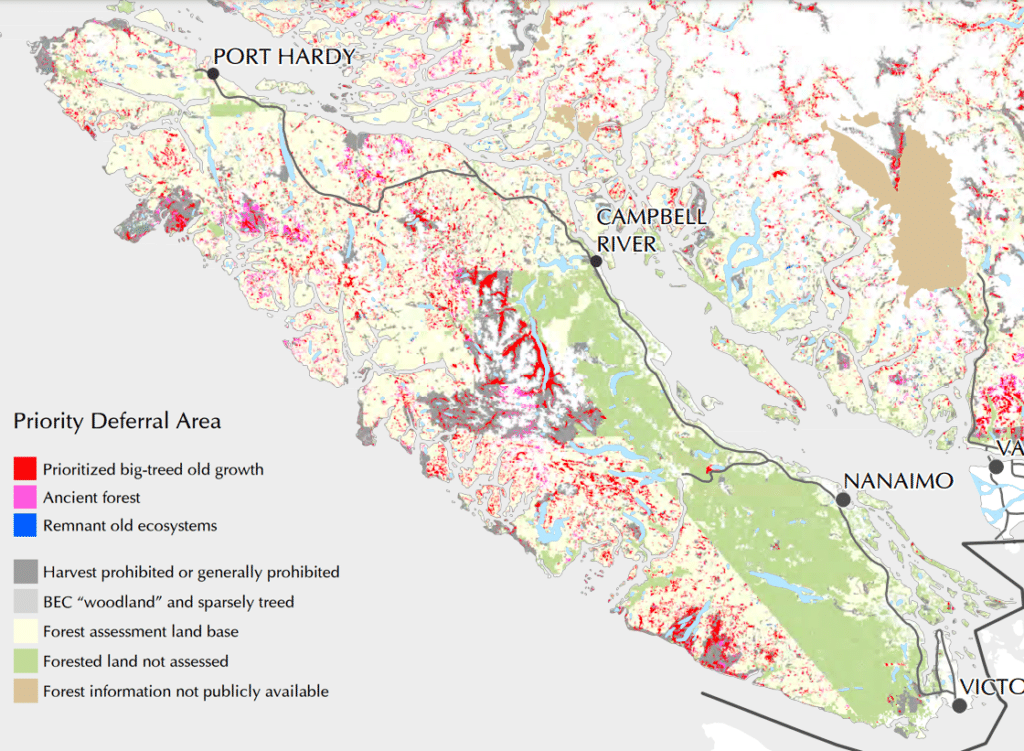

The scientists have also released a series of maps detailing the location of the at-risk old growth.

On Vancouver Island, proposed deferrals dot the landscape, concentrated in western and northern regions.

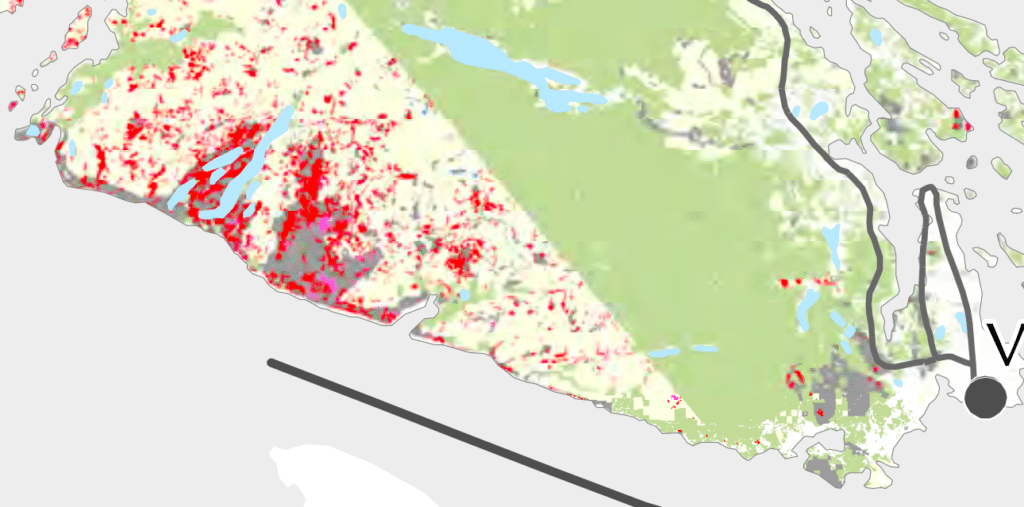

This map shows priority deferral areas in red, pink and blue. The red is big-tree old growth, the pink is ancient old growth, and the (rare) deep blue is remnant old growth, in ecosystem types where little old growth remains.

The map shows priority old-growth ecosystems whether or not they are already protected. That explains the denser areas of red in the Carmanah Walbran area, to the south, and the Strathcona region, the the middle.

Zooming into the South Island, it is perhaps noteworthy that one of the larger concentrations of proposed deferrals, outside existing protected areas, is the area around Fairy Creek, where old-growth blockaders and police have clashed for more than year in the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

The large swath of green that sweeps down the east side of the Island indicates private land, which was not part of this process. Private forest lands are managed separately from provincial Crown lands, and according to many observers, with little oversight or regard for the preservation of ecological integrity.

Although the vast majority of the province’s forests are managed as Crown lands, the reverse is true on the southeast of Vancouver Island. A massive chunk of the Island became private in the 1880s as part of the E&N Land Grant, a historical transaction that the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group calls a “clear act of colonial theft.”

This land remains largely private, with much of it now managed by Mosaic Forest Management and owned by TimberWest and Island Timberlands.

The province’s current efforts to improve old growth management do not apply on these lands, despite the fact that they cover a large portion of the rare and endangered Coastal Douglas Fir ecosystem, where scientists have recommended an immediate moratorium on all old-growth harvesting.

A separate map shows, in orange, areas identified by the scientists as “recruitment forest,” meaning younger forests that, if left standing, have the best potential to develop the characteristics of old growth forests in the future.

The panel identified these forests in ecosystems where old growth is rare or gone. If left to grow old, these areas could help prevent the loss of species that rely on older forest ecosystems.

Although the panel recommended these forests be deferred from harvesting, too, the government has yet to indicate how or if it will act on that recommendation.

More maps and information is available on the government website and in the technical report.

The way forward is still murky, and big questions over First Nations rights and title still hang in the air.

The Narwhal reports that Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, has accused the province of “hiding behind First Nations people” by burdening them with a decision on the deferrals without adequate support. [end]