The Discourse is telling stories about financial inequality, informed by our communities. This story responds to a reader’s question, submitted through an audience survey.

Residents of British Columbia are feeling the pinch amid sky-high prices on essentials, including housing, gas and groceries.

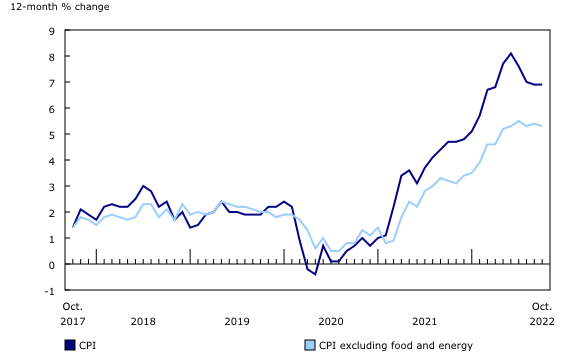

The technical term for this harsh reality is inflation. Every month, Statistics Canada calculates the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures the cost of a fixed basket of goods that represents what an average Canadian household spends its money on.

The change in the CPI over time is the inflation rate. When the inflation rate goes up, it means that Canadians have to spend more money to get the same stuff. The CPI went down slightly in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but hit pre-pandemic levels in March 2021, and has since risen dramatically. The most recent data suggests that Canadians are spending seven per cent more on goods and services than they did a year ago.

But not everyone suffers from rising inflation. “Some groups of Canadians have profited immensely from the acceleration of inflation,” according to a recent report by the Centre For Future Work, based in Vancouver. “In fact, for the business community as a whole, profits have never been better.”

After-tax corporate profits now account for 20 per cent of Canada’s GDP, up from about 15 per cent before the pandemic. Corporate profits now take a bigger slice of the economic pie, while wage workers — and, to a lesser extent, small businesses — end up with less.

That jump in corporate profits has been concentrated among some key sectors, including oil and gas companies, housing developers and some retailers, the report says.

What’s causing this inflation?

A few major factors have contributed to rising prices, according to the report. Those include a rebound in economic activity following pandemic reopenings, supply disruptions related to the pandemic and shifts in consumer demand, and a global energy price shock sparked by the invasion of Ukraine.

In some cases, large companies have used their outsized power to take advantage of these shocks, demanding higher prices to drive booming profits.

“Gasoline prices doubled because of the actions of a global cartel, speculative behaviour in a financialized futures market, and the oligopolistic power of large energy-producing firms — who have been given authority (under Canada’s current energy policy) to unilaterally and dramatically increase prices even though the cost of producing gasoline in Canada has hardly changed at all,” writes Jim Stanford, the director of the Centre For Future Work and the author of the report.

And the Canadian government is now investigating major supermarket chains to find out if they have unfairly used their market power to pad profits at the expense of consumers, who are facing huge increases in the cost of groceries.

What’s the government doing about it?

The Bank of Canada has committed to tackling rising inflation aggressively, and bring it down to a target of two per cent. Its primary tool to accomplish this is by increasing interest rates. The Bank of Canada has increased its overnight lending rate dramatically this year, from 0.25 percent in January to 3.75 per cent in October. Another increase is expected next week.

The hikes come at a huge cost to homeowners with a variable mortgage rate, as well as those seeking new mortgages or renewals.

The effect of this is to “throw a giant bucket of ice water over the entire economy,” Stanford said in a recent interview with CBC’s Front Burner podcast. He criticizes this action as a blunt tool, one that hurts workers, throws people into unemployment and fails to address the real causes of inflation.

“They are asking Canadians who work for a living to accept a permanent reduction in the real standard of living and a permanent shift in the overall economic pie from workers to the businesses that workers work for — first and foremost energy companies and the housing developers and the supermarket chains who’ve done so well from this current inflation.”

Alex Hemingway, a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, echoed that sentiment. “Bringing demand in line with supply by making people poor is not a solution to the cost of living problem,” he said in a recent interview with The Discourse.

“When we’re talking about the negative effects of inflation, we’re talking about how it’s raising the cost of living for people, and that’s what needs to be addressed,” Hemingway said. “And so let’s look at some of the big drivers of the cost of living that are putting pressure on households.”

Is there a better way?

The Centre For Future Work report outlines a suite of recommendations for tackling high inflation and its unequal impacts. It advocates for patience in allowing some of the economic shocks to even out, while balancing goals of a productive economy and labour market with that of reducing inflation.

The report suggests that policymakers could use more flexible tools to encourage lending for investments that strengthen the economy while discouraging unproductive investments, such as financial and real estate speculation.

New structures or policies could also allow for coordinated collective bargaining across industries, to ensure that real wages keep up with the cost of living. Many other countries, particularly in Europe, have brought about better employment and income outcomes in this way, the report says.

Governments also have the power to reduce or control prices for consumers on many goods and services, such as rent, public transportation and child care. They can also use tax policy to redistribute wealth from those who have profited from high inflation to those who have been most hurt by it. Governments can also ramp up investments in affordable housing and the transition to a green economy.

The high interest rates enforced by the Bank of Canada actually serve to disincentivize those needed investments, says Hemingway. For non-profit housing organizations, for example, “having these very high borrowing costs actually makes it extremely challenging to get new affordable housing projects off the ground, because borrowing costs are such a big component of making those projects work economically.”

But the big-picture solution will require stronger collective power: institutions, including but not limited to unions, that “can help offset the concentrated power of those at the top,” says Hemingway.

“When labour [organizing] has been more powerful in our history, those are the periods in which we’ve seen new social rights — won new social programs, health care, unemployment insurance, minimum wage, the eight-hour day, all of these things,” he says. “I think we’ve kind of forgotten the success that can be had by that hard work.”

This reporting was made possible through the financial support of Coast Capital, a member-owned cooperative. The article was produced with full editorial independence; Coast Capital was not involved in the story selection, reporting and editing process.