Photos by Madeline Dunnett/ The Discourse.

On a muggy day at the end of July, Caitlin Pierzchalsi, executive director of Project Watershed, spent time trekking through the Kus-kus-sum site to share its progress over the last five years.

Project Watershed is a Comox Valley-based non-profit that oversees the project along with K’ómoks First Nation and the City of Courtenay.

The walk began at the southeast side of the site which sits along the K’ómoks Estuary. It doesn’t look like much at the entrance, but tucked behind the giant piles of dirt is the restoration area known as Kus-kus-sum, translated to “very slippery” in English.

Project Watershed is in the process of relocating these soil piles to a new site after a new provincial protocol regarding soil contaminants came into place. The protocol changed regulations that had to do with how soil contaminants are dealt with and redistributed in certain areas.

Read also: Soil remediation presents challenges and opportunities for Kus-kus-sum restoration

Pierzchalski said that right now, the restoration team has a few sites in mind for the contaminated soil but they are still working out the next steps and relocation process.

While doing restoration work, old logs appeared beneath the ground at the Kus-kus-sum site.

“This is just really old wood we’ve pulled out of the ground,” Pierzchalski said, adding that a lot of wood has been buried underground over the years. She said the restoration team hopes to keep most of the wood, as it is a good ecological feature to leave in the area.

“We do try very hard not to generate too much waste out of [the] site. So whenever possible, like with the large wood for example, we try to use that on site because it can be quite a great habitat feature. It adds complexity and slowly biodegrades over time, adding nutrients to the soil.”

Remnants of the former sawmill and log boom can also be found throughout the site, and Pierzchalski said the project team spent some time removing creosote — an oil product used to preserve wood that is toxic to many species.

The flowers popping up at Kus-kus-sum are native to the area, and Pierzchalski said the Project Watershed team has seen a variety of different bee species flying around to pollinate them.

As she explained this, one of the bees decided to come out and say hello.

Project Watershed and volunteers planted entirely native plants for the area, and are constantly trying to pull out invasive species that pop up.

“You kind of have to pick your battles,” Pierzchalski said.

She said the notorious scotch broom was the plant the restoration team had to keep their eye on the most because it is very invasive.

But, she said, a lot of the native plants appeared on their own without being planted, such as cattail.

“That was really cool to see.”

A steel piling wall separates the Kus-kus-sum site from the Courtenay River. It has been there since the Field Sawmill began operation on the land in 1949. The sawmill closed in 2004, but the wall and concrete foundation remained.

In a previous interview with The Discourse, Pierzchalski said restoration work at Kus-kus-sum is nearing completion, but the project is still short about $1 million in funding to get to the finish line and remove the wall and other remnants from the sawmill.

“If we are able to close this million-dollar contribution gap, we’ll be able to finish the project and remove the wall in the winter 2025/2026,” she said.

Moving northwest along the site, the grasses and plants become more mature, as they were planted earlier.

Sitka spruce were logged extensively after colonization because it was often used for masts on sailing ships.

This species also has a lot of historical importance for K’ómoks. In an article from The Tyee, K’ómoks Chief Ken Price said the Sitka spruce trees alongside the Courtenay River were often used to hang cedar boxes for tree burials.

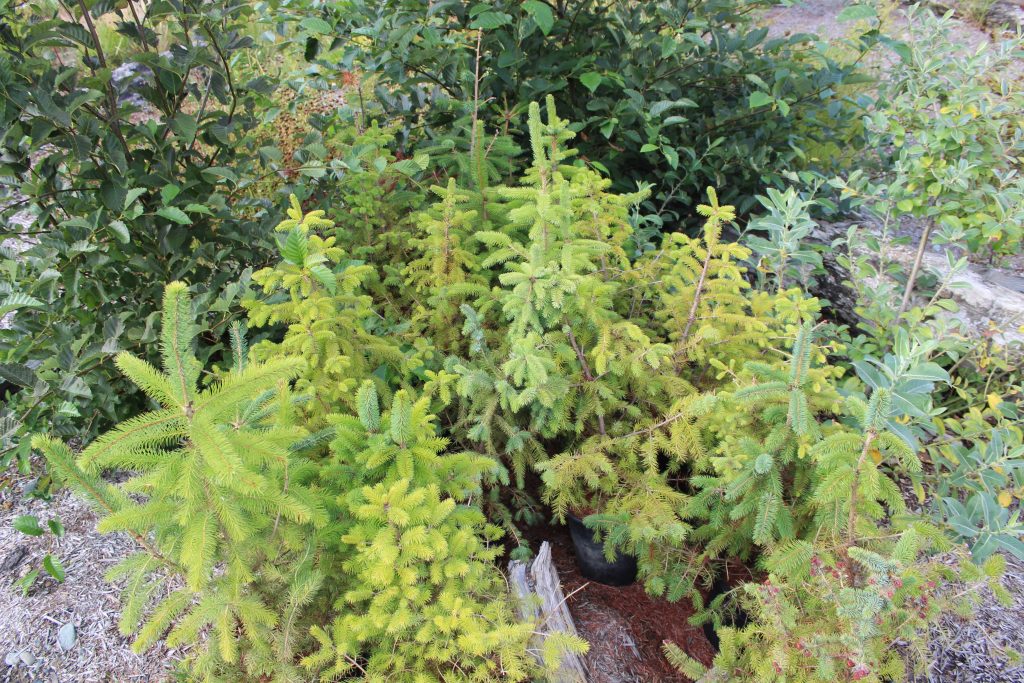

However, before the Sitka spruce have their chance to grow big at Kus-kus-sum again, other plant species need to grow to promote a healthy environment, and that’s what is seen coming up now at the site.

Pierzchalski said alder and cottonwood trees have been particularly successful in the past few months.

Deciduous species are good at establishing beneficial nutrient relationships within the soil and fixing nitrogen, benefitting other species as well. After the trees die off, they will leave good soil and more room for the later successional species such as Sitka spruce. She said these early successional trees are doing well on the site already.

“It’s just really cool to see. I think this year specifically, I really saw them greening up in the spring. That was really noticeable … We’re really starting to see the future of Kus-kus-sum and what it will look like in a few years time, so that’s exciting.”