About 40 people gathered at a small church in Cumberland to learn about where their water comes from — and why it’s at risk — on World Water Day.

Though the gathering on Saturday was small, its topics were big. Preserving glaciers was the international theme of this year’s global event, which the United Nations has marked since 1993.

The Cumberland gathering, hosted by the Cumberland Community Forest Society and Cumberland’s Weird Church, began with a screening from the PBS docuseries H2O: The molecule that made us, which dives into a broad-scale perspective on water’s impact on all living things.

The event then zoomed in even closer on Comox Valley’s own watersheds, with a presentation by Cumberland Community Forest Society executive director Meaghan Cursons.

The watershed’s long, meandering history

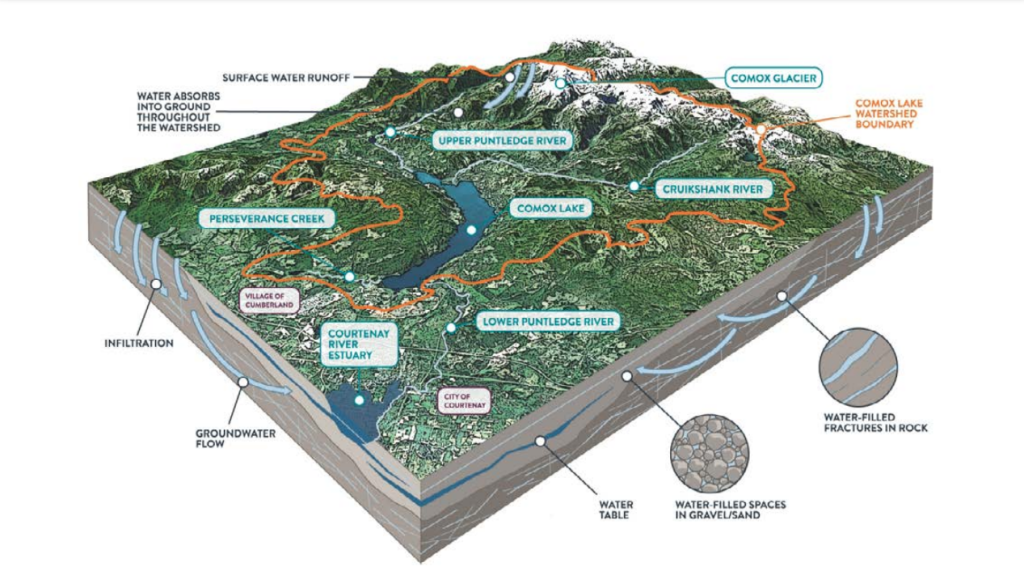

A watershed is an area of land that drains into rivers and lakes which then flow into a common outlet. Cursons said that watersheds can vary widely in size, from small to sprawling.

She also described how tiny watersheds fit into a series of broader regional ones, which she likened to “Russian dolls of watersheds.”

“You get these massive ones, like the Pacific Ocean Watershed,” she explained. “And then we start to scale it down, you have the Salish Sea Watershed.

If you zoom in closer, she added, you find watersheds such as the Comox Lake Watershed, which feeds into Comox Lake and provides the Comox Valley’s municipalities with their drinking water.

But you can take it even further, she said, scaling down even further to the Perseverance Creek sub-basin.

“Take it down a bit more,” she said, “and you have a river that runs through your backyard.”

In B.C. many watersheds are fed by glaciers, and Vancouver Island is no different. The 461-square-kilometre Comox Lake Watershed includes the Comox Glacier at its headwaters, according to the regional district.

Vancouver Island as we see it today has its origins at the end of the last Ice Age.

According to a study by Richard Hebda, former curator of botany and earth history at the Royal B.C. Museum, most of the province was covered in glaciers during that period, between 17,000-14,000 years ago — known as the glacial maximum.

The Comox Valley was also glaciated during this time.

As the climate began to warm, Vancouver Island’s glaciers began to melt faster, and the massive ice sheet covering most of the island retreated between 14,000-10,000 years ago, leaving behind gravel moraines near the area’s headwaters.

Today, like many of the province’s highest-elevation areas with year-round ice and snow cover, the Comox Glacier is a remnant of the former ice sheet.

Glaciers in K’ómoks First Nation’s culture

The geological story of this region also lines up with an integral part of K’ómoks First Nation’s history and connection to this land, Cursons added.

According to the Pentlatch story of xqʷənɛs (Queneesh, meaning whale), long ago a great white whale emerged from the glacier to save the people from a terrible flood.

But despite being an important cultural landmark in the area for millennia, and at the heart of the Pentlatch origin story, the Comox Glacier is shrinking.

University of Northern B.C. geography professor Brian Menounos — the Canada Research Chair in Glacier Change — estimates that the glacier will have vanished by the middle of this century, along with all Vancouver Island’s year-round ice.

Historical threats to the local watershed

The UN’s World Water Day website states that preserving glaciers — this year’s global theme — is a matter of survival.

“For billions of people, meltwater flows are changing, causing floods, droughts, landslides and sea level rise,” the international body’s website states. “Countless communities and ecosystems are at risk of devastation … We must reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow down glacial retreat.”

But much of the local area has already faced threats from the industrial extraction of fossil fuels — long before the dangers of global climate change were widely known.

“One of the greatest impacts on this landscape was the discovery of coal,” Cursons told the audience.

She touched on the local history of the E&N railway, and how coal baron Robert Dunsmuir — at the time, the province’s richest man — pushed to build the railroad up Vancouver Island due to his interest in potential coal reserves along the route.

The biggest and most productive coal mine, Cursons explained, was on the shores of Comox Lake: the No. 4 coal mine.

“The landscape from the 1890s probably looked a bit like Mordor,” she said, referencing the evil and barren realm from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

“The entire thing had been cleared and we had massive coal-mining extraction and operation happening right there on the shores of Comox Lake.”

She said it would have been a “very dramatic and impacted landscape,” not just forests as one might expect.

The watersheds of the area were also dramatically altered by logging, as the industry made its way up into the Comox Lake Watershed.

The Comox Lake Watershed was mostly harvested over just a few years starting in the late 1920s.

Damming in the watershed in 1912 also disturbed the area.

“What we ended up with is basically already a destroyed riparian landscape around Comox Lake,” Cursons said.

A unique watershed, still under pressure

Cursons said there are still many pressures on Cumberland’s local watershed.

Though much of the Cumberland Forest is now protected, industrial logging continues today near the community forest’s borders.

Increasing tourism is also adding to human pressures on the area.

Cursons shared images of recreational activities such as dirt biking and partying within the Cumberland Lake Ecological Reserve, which she said pose threats to the environment, as well as increase the likelihood of forest fires.

But unlike many waterways around the world, the Comox Lake Watershed is fortunate to not be downstream from industrial agricultural activities.

It is also very clean and nutrient poor, she said, “which sounds like not a good thing, but it’s actually a great thing for drinking water.”

This is because low-nutrient bodies of water — known as oligotrophic lakes — contain low levels of aquatic vegetation such as algae, as well as higher oxygen levels.

That means their waters tend to be clearer, and generally safer, for people to drink.

Cursons added that the Comox Lake Bluffs Ecological Reserve is also revealing interesting data about how ecosystems adapt as the climate changes over long arcs of time.

The reserve was established to protect the area’s unique ecosystem. It is the hottest, most south-facing aspect of the Comox Lake Watershed. The area has a lot of arbutus trees.

“It’s like a Mediterranean climate,” Cursons said, similar to the climate in places like in California, Oregon or the lower Gulf Islands.

As a result, it could help predict what some regions might look like in the future after impacts from climate change.

In the meantime, Cursons said, the Village of Cumberland, the CVRD, and local organizations such as the Cumberland Community Forest Society and Comox Valley Land Trust are working together to ensure the local watershed is protected and ecologically healthy.

“It’s a beautiful space, and many of us have a very intimate relationship with it,” she said. “Healthy, functioning spaces are what we need to have healthy, safe drinking water — and we are doing it, slowly but surely.

“We’re seeding our actions and are tending the planet now … knowing that people will come after us.”