“It was total freedom to be alone on a mountaintop, lakeside, or river,” says Patrick McIntosh, looking upwards as if his mind wanders back to those moments.

McIntosh takes us back to 2006. He had just moved to Nanaimo, and his intense excitement to explore his new home pushed him out of the city — and into the wilderness. Every few weekends, he would camp in the backcountry, trying to find new spots of marvel.

“It was so incredible,” recalls McIntosh in an interview. “You could go up Nanaimo River road, and end up anywhere.”

But around ten years later, things dramatically changed. Suddenly, his favourite places had become inaccessible. Gates increasingly blocked access to roads that once led him to natural “treasures.”

Suddenly, he started to wonder if it was still worth the effort.

Disappointments in the wilderness

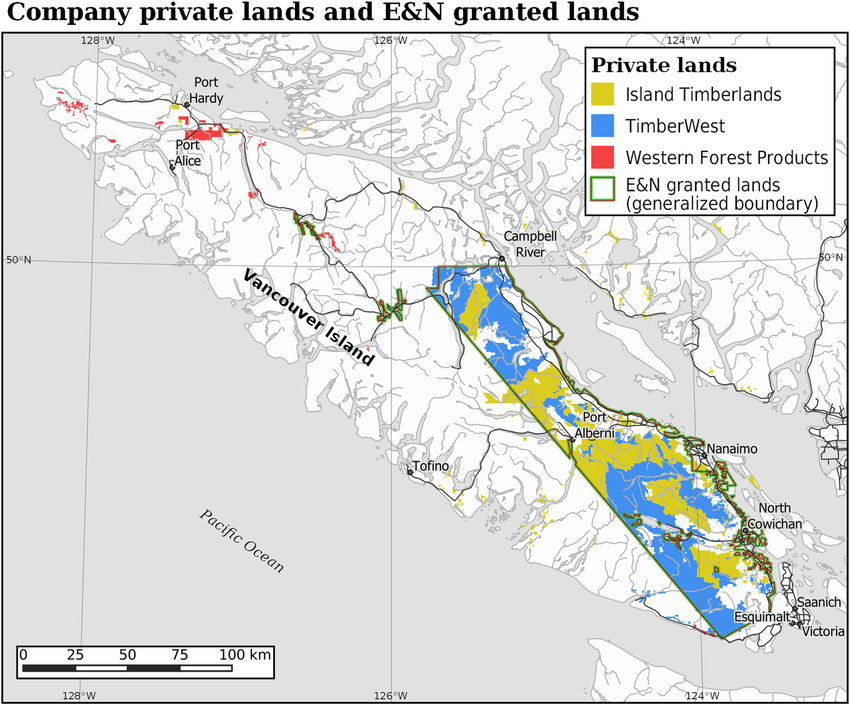

The areas McIntosh describes are on land managed by Mosaic Forest Management, but privately owned by TimberWest Forest Corp. and Island Timberlands.

Mosaic is a forest stewardship business, which in part means it manages “private timberlands and public forest tenures in Coastal British Columbia.” Since 2018, it’s managed forestry assets on behalf of TimberWest and Island Timberlands, Mosaic explained in an email.

Mosaic’s website describes its mission as helping “protect the cultural values of our Indigenous partners, provide sustainable forest stewardship and environmental services, and offer a variety of recreational opportunities.” Headquartered in Vancouver, the firm also has offices in Nanaimo, Campbell River and Nanoose Bay.

McIntosh is not alone in his feelings of disappointment at finding himself blocked from his favourite getaway spots.

Across Vancouver Island, calls are growing for fewer restrictions to the backcountry, especially from recreational motorized groups. It’s also fueling tensions within some communities.

In early August 2024, several dozen people gathered in Frank Crane Arena to express their frustrations at the companies and government they say are excessively blocking off land.

The people at the gathering expressed their mutual love for exploration of the many acres of backcountry land on Vancouver Island. They also discussed how to broaden support for their cause.

But the issue is more complicated than it may seem on the surface. Opening up access raises challenges around complicated ownership of backcountry areas, and concerns for the safety of land and people accessing it.

Concerns for land and public safety

Island Timberlands and TimberWest own vast amounts of the backcountry land surrounding Nanaimo. Many off-road users accuse Mosaic — whose signs frequently adorn the gates blocking access to logging roads — of unfairly restricting public access.

Mosaic said they have many concerns about giving the public access to their “fully privately funded roads.” In an email, a company spokesperson said private forest landowners must manage liability and damages on their properties.

Mosaic said it is also concerned about the “safety of workers and the public, the risks of wildfire, dumping and vandalism, damage to sensitive plant ecosystems, and impacts on wildlife habitat.”

But despite the company’s rationale for restricting access, many outdoor recreationists feel they’re not completely valid.

“Gates for the sake of gates,” said Teresa Grigg, a member of Open The Gates (OTG), a non-profit group devoted to expanding access to Vancouver Island’s backcountry.

She said she’s spent her “entire life in the woods,” where her dad worked, and understands safety concerns within the forestry sector.

That’s why she insisted she’s not against gating off active logging zones, particularly the dangers of heavy equipment and loose timber.

When logging trucks are fully loaded, she explains, stopping and maneuvering is difficult, making collisions with nearby recreational users risky. Further, if a hill is being logged — which is common on the island — a dislodged log can “come racing down the hill and across the road.”

“A getaway log can wipe you out in a split second,” says Grigg.

Despite that, however, she doesn’t agree with the extent of current restrictions. For her and her peers in OTG, going into the backcountry is “a way of life,” Grigg said. “And all of that is being taken away.”

‘Jaw-dropping parts of Vancouver Island’

Lory Fairfield, the Campbell River representative for the Four Wheel Drive Association of B.C., is familiar with off-roading activities, and understands their potentially negative environmental impacts and Mosaic’s safety and environmental reasoning.

For example, driving through streams hurts the ecological system, he said, and such behaviour is considered “bad form” in the off-roading community.

He admits some off-roaders may break this norm, but their peers hold them accountable. Fairfield said if someone posts a video of driving through water, “they get railed on social media.”

But he remains unconvinced of the need for so many gated roads.

Fairfield has been taking his “lovely and old” Jeep into the backcountry for quite some time, and doesn’t believe companies’ understandable fears of litter, fire and vandalism are justified.

He and friends he rides with pick up garbage they see, and make an effort to clean up after others.

“As you’re driving along, if you see a Kentucky Fried Chicken Bucket, you stop and pick it up,” Fairfield said. He always has garbage bags on hand.

For Fairfield and others who enjoy driving in the backcountry, the benefits outweigh many of the concerns when users try to lessen their impacts on the land.

The value of access for Fairfield is almost indescribable.

“It’s therapeutic,” he said, describing the sound of loons waking him up in the morning, or dangling his feet into cool water.

Jonathan Binnington, an avid off-road motorcyclist, shares Fairfield’s admiration for nature.

And while he shares others’ frustrations with gates impeding his access, he has mixed feelings about the forestry industry.

If it weren’t for the logging sector, there would not be many roads in the first place to get him to the “impressive, breathtaking, jaw-dropping parts of Vancouver Island.”

Binnington also shares a positive outlook about backcountry users, and argues that some of Mosaic’s concerns — from vandalism to fires — would be less of a problem if access were more open, because he believes more users could help monitor for fires.

The provincial wildfire service says 40 per cent of wildfires are human-caused, according to its website, with the majority started by lightning.

Ownership confusion and opposition

Vancouver Island’s land is unique because its ratio of private to public land ownership is drastically different from that in the rest of the province.

Across B.C., just five per cent of the total land base is privately owned, according to research published in Canadian Geographies journal in 2020, while Vancouver Island has 23 per cent fee-simple title lands.

Yet in Mosaic’s case, because it is not the actual landowner, understanding who to contact to request access, and which lands are private versus public, is unclear to many.

“It’s a complicated ownership web,” said Erik Piikkila, a Vancouver Island forest ecologist. He said the question of “who’s got authority” on the land is in many ways “a grey area.”

It’s a grey area that’s created a sizable communication barrier between members of the public, private companies, and the government.

“Everyone is operating in isolation,” he said.

The B.C. Ministry of Forests said it doesn’t oversee access to private property, only provincial land.

“The Province does not have jurisdiction over public access to areas of private forest lands that are not part of B.C.’s Crown land, such as those managed by Mosaic on eastern Vancouver Island,” a spokesperson said in an email.

‘The great land grab’

One research project exploring the complex issue of private land ownership on Vancouver Island is the Great Land Grab.

One of the project’s researchers is Michael Ekers, an associate geography professor at the University of Toronto, has extensively studied private, unceded lands on Vancouver Island.

Ekers said there “is a ton of misinformation” about land ownership on the Island.

To make matters more complicated still, public-sector investment funds have major financial stakes in the two forestry firms involved in the road-gating controversy.

TimberWest is jointly owned by the B.C. Investment Management Corp. (BCI) and the Public Sector Pension Investment Board (PSP), created by the provincial and federal governments respectively. The two public funds hold significant investments in Island Timberlands, as well.

BCI’s website states that BCI and PSP acquired TimberWest in 2011; three years later, the investment firms invested even more into Island Timberlands after decades holding a stake in it.

BCI states that it “operates independently from government;” the province appoints its board chair and two other directors. PSP is a federal Crown corporation whose board is appointed by Ottawa, but says it operates “at arm’s length.”

In one of Ekers’ publications, Land grabbing on the edge of empire, he states that the arrangement resulted in nearly 600,000 hectares of Vancouver Island “falling under the control of one management company” — Mosaic.

After researching the companies’ paper trail, Eker said there is a lack of public transparency, because the companies and pension plans behind them are “really opaque … it’s really hard to know what’s going on.”

Origins in 1887 railway land grants

But while outdoor recreationists are upset about the recent blocking-off of roads they previously used on the Island, the issue actually traces its origins back more than a century.

According to Ekers’ research, many of the complicated ownership issues date back to the province’s land grants of the E&N railway in 1887.

The grants took land from multiple Coast Salish and Nuu-Chah-Nulth nations, the Great Land Grab project’s website states, unfairly privatizing the territories of Coast Salish and Nuu-Chah-Nulth nations, and “disregarded earlier Crown acknowledgments of Aboriginal title.”

As Robert Morales, chief negotiator of the Hul’qumi’nu Treaty Group (HTG), previously told The Discourse, the grants were “an unlawful act.”

The nations never surrendered rights, title, or jurisdiction to the land during the 19th-century land grants.

As outdoor enthusiasts debate access to the beloved Vancouver Island backcountry, a larger question of addressing Indigenous title and rights in the same privatized areas.

Brian Thom, an anthropologist and associate professor at the University of Victoria, was a negotiator with the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group for ten years during their ongoing treaty talks, from 2000-2010.

Today, HTG is in stage five of treaty negotiations, and a key issue continues to be the almost two-thirds of Hul’qumi’num land that was within the E&N granted area.

‘How can we live together?’

Thom argued that, if First Nations people still have title and rights to all those E&N granted lands, their territories shouldn’t “be governed at the whim of these large corporations.”

“If Aboriginal title and fee simple title both exist simultaneously on those lands,” he asked, “what should we do about that?

“How can we live together? How can we work together?”

Many off-roaders share a common refrain in hopes of resolving who can access the areas currently gated off: working together, and collaborative problem-solving.

Recreationists’ proposed solutions include holding public discussions to understand the land ownership better; opening the gates up in areas unless they’re being actively logged; and even some kind of system where users can check in and check out to drive past the gates.

However, conversations about access cannot happen without First Nations involved, both Ekers and Thom agree.

That’s essential to Dallas Smith, president of the Nanwakolas Council, which brings together First Nations to protect their rights and engage with industry, government, and partners.

“We realized we needed to get involved and talk about why our territories are important to us,” Smith said in an interview, explaining how the council has amplified Indigenous voices advocating for their stolen lands — and First Nations’ right to benefit from their territories economically and sustainably.

Over the years, he has been in touch with Mosaic about the areas it manages, because “they have rights to all this — I’ll use my air quotes — ‘private’ land that is ours, and should be part of treaty discussions,” he said.

Mosaic has been a challenge, Smith added, but he hopes to speak with the company about working together to incorporate sustainable values into how it manages the areas it oversees.

“It has taken time, patience and the odd threat,” he said, “to make them realize we’re not going away. This discussion has to happen.”

Questions of access to Vancouver Island’s backcountry, and its underlying title, are what Thom describes as “the big elephant in the room.”

High demand and misunderstood expectations

It’s not just First Nations who are pushing to be involved in discussions around access to privatized backcountry areas.

Some conservationists are also raising ecological concerns about the little remaining Island wilderness — and worry that increasing motorized vehicle access for recreationists could hurt ecosystems.

Meaghan Cursons, executive director of the Cumberland Community Forest Society, is very aware of many outdoor enthusiasts’ desire to enjoy wilderness areas on their vehicles. But she is also aware those same vehicles can harm the very wilderness they love.

Motorized vehicles, she explained, cause erosion and damage forest floors, harming ecological and hydrological functions.

The backcountry is also home to much wildlife, including bears, deer, birds, and many other species — all of which can be disturbed by noise, damage to the forest, and hunting activities.

Forest ecologist Piikkila agrees elk poaching, vehicle noise and wetland damage are concerns. In particular, the Island is home to rare and fragile wetland ecosystems.

It only takes a couple wheels driving over some wetland areas, Piikkila added, to permanently harm them.

Piikkila also worries about the increased number of people entering if gates open.

Remote forests, he fears, could get overwhelmed; he’s seen some wilderness areas get so popular that their sensitive ecosystems get “trampled to death.”

But for Piikkila, wildfires are the main reason for restricting access. Winds can turn small campfires or cigarette butts into raging infernos.

However, Cursons acknowledges that small motorized vehicles on primary logging roads wouldn’t have nearly the same level of negative environmental impacts as off-roading on less-traveled wilderness routes.

On the other hand, there are benefits to giving recreationists more opportunities to appreciate Vancouver Island’s beautiful nature.

“It would be great if there was motorized access that would let people get way out there on primary roads,” Cursons explained, adding she’s sometimes jealous of the spots such roads can reach.

Demand for access to the backcountry is growing, she noted, while the amount of publicly available land is not. That combination puts pressure on conservation land and public parks — which could be eased by allowing more access to some primary backroads.

Part of her work is educating people on their rights when accessing certain lands on Vancouver Island. She knows many come expecting unimpeded backcountry access — but are confronted by restrictions.

She worries that some tourism campaigns lead to misunderstandings about access.

Tourism Vancouver Island’s website describes it as a place with an “abundance of outdoor recreation opportunities and peaceful getaways.”

One study for the British Columbia Regional Tourism Secretariat demonstrates a steady rise in international travellers to Vancouver Island in 2023 compared with the two prior years.

The increased demand for remote backcountry access is also increasing tensions “between expectations, available lands, and people’s understanding of entitlement,” Cursons said.

Such tensions over what people feel entitled to in the outdoors, she believes, only worsens the ecological pressures on the landscape — and within communities.

“For fuck’s sake, let’s figure this out,” Cursons said. “Because by not figuring it out, it’s putting negative pressure on conservation areas.”

That’s why she’s willing to help motorized vehicle users gain some type of increased access to backroads — because it could help protect other conservation lands.

Who gets a gate key?

Greg Forsythe, one of Open the Gates’ founders, explained that his desire to explore the world made him start the organization.

Surrounded in his home by multicoloured pins from around the world, and rocks and fossils from multiple continents, he laments that backcountry exploration closer to home has led to such tensions.

But one particular sticking point for Forsythe is that some people and groups have been given keys to the Mosaic gates, but with a fee and conditions.

One such group is the 600-plus-member Island Rangers Society, which explains on its website that its access agreement with Mosaic lets them act as the “eyes and ears” on lands the company manages — for instance reporting illegal activity — in exchange for weekday access.

The role is voluntary, but members pay an annual fee to the organization.

Fairfield, with the Four Wheel Drive Association of B.C., calls them the “police” of the backcountry — and alleges they stop and report unauthorized users. (The Island Rangers website emphasizes its members are not security personnel.)

Mosaic said via email it does allow access to some backroads at designated locations — but only on weekends.

The company said it signs access agreements with groups and clubs like the Island Rangers who “demonstrate a track record of responsible use and whose activities are consistent with Mosaic’s values of ensuring public safety and protecting the environment.”

Still, tensions seem to be far from any resolution — between disappointed off-roaders, the select few with coveted gate keys, active logging operations, and the First Nations whose territories make up the lands in question.

For some, that story is personal and goes back generations.

Smith, with Nanwakolas Council, said he knows people in his community who are confused why they can’t access certain areas where their families once spent time going back generations.

“How come we can’t go out to this area,” he wonders, “where I know my great-grandfather picked berries?”