In November 2021, Island Health partnered with Lookout Housing and Health Society to open the Cowichan Wellness and Recovery Centre to combat the local manifestation of the ongoing overdose crisis in B.C. Situated controversially at 5878 York St., across from the Warmland House shelter, the wellness centre offers a suite of services, including mental health support and the region’s Overdose Prevention Site (OPS).

Last year, 40 people in the Cowichan Valley died of illicit toxic drugs, the most the region has experienced in a single year since B.C. declared a public health emergency in 2016. But none of last year’s overdose deaths in the region occurred at the OPS, despite overdoses being a regular occurrence there. Clients of the wellness centre are primarily unhoused or precariously housed, and they credit the services there with improving health outcomes for the street community.

They say the centre has become a life-saving community hub where people can not only access, test and use drugs safely, but also connect to health care, detox and treatment supports. Clients say services at the centre have also reduced a need to engage in criminal activity, like theft, to support drug use.

“OPS is very vital to the community, very vital. If we didn’t have it, I think there would be a lot more deaths,” says Tracy, a client of the wellness centre and overdose prevention site.

Read also: Cowichan community comes together to address impacts of new wellness centre

What clients are saying about the wellness centre

For many clients, the wellness centre is more than the sum of its services. While they value the services, many of which already existed in various locations, they say that part of the wellness centre’s appeal is as a hub, a place where they can go and feel safe.

Justin Sylvester, 38, lives in a cabin at The Village temporary housing site at 610 Trunk Rd. Previously, he was at the COVID-19 tenting site on St. Julien Street after several years of living on the street. He says that the street community welcomed the announcement of a wellness centre.

“The general acceptance of it was huge,” he says.

Until he broke his foot six months ago, Sylvester used to walk over to the wellness centre every day. He would go to the OPS to smoke “down,” the street name for what is primarily a mix of opioids frequently including fentanyl. He also accessed safer supply and opioid agonist therapy medications at the health clinic. The visits were also a chance to find out the news of the day.

“It’s a good place to catch up on who’s been hurt or who’s passed on … we lose friends like it’s going out of style,” says Sylvester, who explains that staff at the centre are willing to pass messages along to other clients. He adds, “They won’t let you walk out the door unless you are well. It’s not like you have people stumbling out the door that are impaired, walking into traffic or picking on elderly people or something like that. That doesn’t happen.”

Robert Knippshild, 41, grew up in the Cowichan Valley and says he had been unhoused for about 15 years due to his opioid addiction until landing a spot at the Sq’umul’ Shelh Lelum’ supportive housing development that opened last April on Paddle Road. Before then, the centre served as a daily refuge from the rigors of living on the street, he says.

Perpetually sleep-deprived because he didn’t want to sleep at night out of fear that people would steal his belongings, Knippshild says he often would take a long nap at the OPS while seated at one of the injection booths, warm and relaxed with the knowledge that everything would be okay.

“When I was homeless, it was a place where you could feel safe,” he says.

Tracy, 52, also was a regular at the wellness centre until she moved into a unit at Sq’umul’ Shelh Lelum’, which provides mobile health services. She still goes to the OPS occasionally to use drugs, or just to see friends. “If I want to go find anybody, that’s where I go first, because they’re either inside or waiting to go inside.”

The thing she likes best about the wellness centre is that the staff aren’t judgemental about people’s choices and circumstances. “Nobody judges you on anything. If they can help you in any way shape or form, they will,” she says.

What the wellness centre offers

The premise of the $2.8 million wellness centre is to “co-locate multidisciplinary services within the same location” and provide “low-barrier” access to them, says Jessica Huston, operations manager with Duncan Mental Health and Substance Use Services, who oversees the centre.

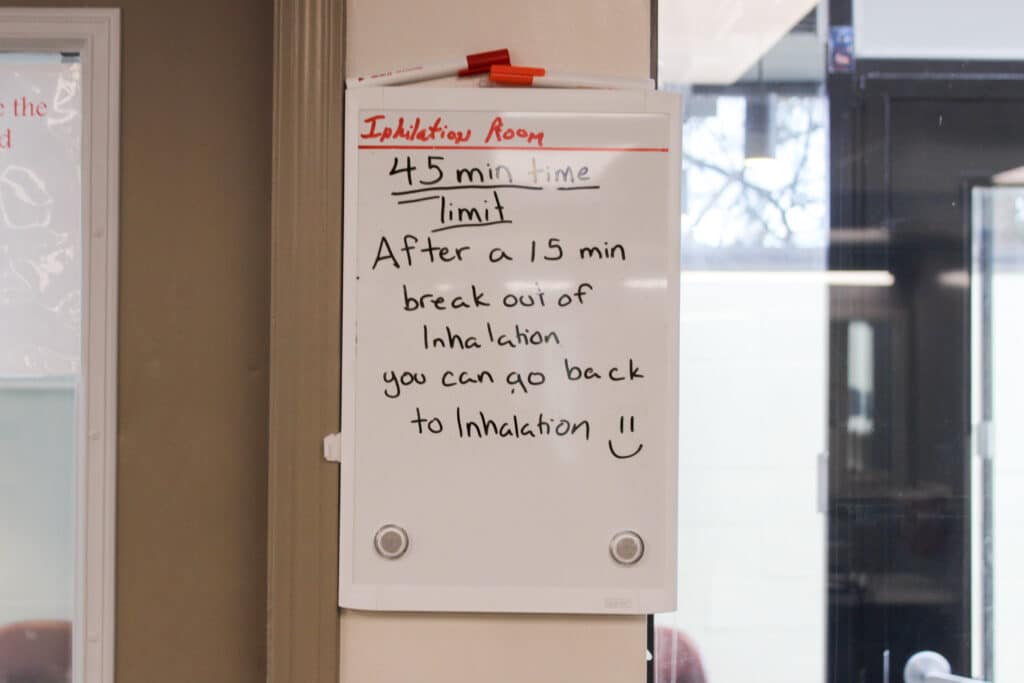

An outdoor set of stairs leads clients through a reception area and to the second floor of the wellness centre, which includes the OPS, open daily from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. The OPS has capacity for 10 people inside to use at injection booths and eight people outside to smoke drugs in an inhalation area that resembles a large covered bus stop. The indoor booths include a chair, mirror and extensive exhaust system that Island Health says is needed to expel any vapours from the drugs.

This overdose prevention site is run by Lookout Housing. Previously, the OPS, which opened in September 2017 on 715 Canada Ave. before moving in April 2018 to 221 Trunk Rd., was run by the Cowichan branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Inside the new OPS area, there is also a chillout room; an exam room for a health clinic where several afternoons a week an addictions medicine physician or nurse practitioner certified in addiction medicine provides primary care and access to alternatives to street drugs; and a clinic room for the tablet injectable opioid agonist therapy project (TiOAT), a four-year pilot funded by Health Canada where 25 participants receive safer supply such as hydromorphone tablets and fentanyl patches.

On the third floor of the wellness centre, there are offices for Island Health outreach teams including the Substance Use Integrated Team (SUIT) of nurses, social workers, substance use counsellors and peer support and rehabilitation and recovery workers. These community-based teams support people struggling with substance use issues.

And at the street level of the wellness centre, there is a lockup area where clients can safely store their belongings, shopping carts and bicycles during visits to the centre.

Having all these services in one setting allows for important collaboration among staff, and makes it easy for clients to be aware of services and access them, Huston says. For example, she says the SUIT team works very closely with Lookout Housing, the addiction medicine physician and nurse practitioners as well as community partners to support individuals they are mutually working with.

“It’s been going really well,” Huston says. In addition to overdoses that are reversed on a regular basis at the OPS, the wellness centre has sent a number of clients to detox centres and treatment programs and then helped them integrate back into the community, she explains. She adds that some of the participants in the opioid agonist therapy project have been able to decrease the dosage of their medications enough so that they are now able to hold jobs.

The wellness centre also ends up providing emotional support for clients, says Lisa Palmer, manager of the overdose prevention site. “A lot of people that come in here on a day-to-day basis just break down and cry because they miss their family,” she says.

Palmer says she wishes people would see clients of the overdose prevention site as individuals with friends and family who miss them.

“They belong to someone and, as the information that is coming out now is the fact that addiction is a medical illness, these aren’t choices. No one wakes up one day and decides that this is the life that they want to live.” Palmer says. “Something has happened and if we spend some time actually really listening to the stories that are being told, we would have a lot better understanding of what causes someone to decide to be in a situation they’re having such pain.”

Saving lives and reducing stigma at the OPS

People with substance use addictions get well-acquainted with how to use Narcan kits to temporarily reverse overdoses with the drug naloxone. Jeffrey “Disco” Bell, 45, lives at The Village temporary housing and says that like many who have lived on the street due to their substance use, he has saved a lot of lives with the help of others. He explains that it often involves a team effort but it can be chaotic with people arguing over what to do, which can waste valuable time.

“If you’re at the wellness centre, that won’t happen,” Bell says. “That’s priceless.”

Each week, the OPS receives an average of 341 visits by people who consume drugs on site, with an additional 60 to 150 weekly visits by people who come for information or supplies but don’t use on site. The number of visits was initially down when the OPS first moved from Trunk Road but are now a bit higher than the numbers at the former site, Palmer says.

OPS clients aren’t required to provide any personal information, Palmer explains. Most of them smoke their drugs instead of injecting them, with clients saying there is often a wait to use the inhalation area. The fan in the inhalation area is quite noisy and can make it hard to speak to clients in distress, Palmer says, but it helps keep clients and staff safe by filtering out pollutants.

About three-to-five times a week, there is an overdose at the OPS, Palmer says.

Three harm reduction staff monitor the up-to-18 people allowed at the OPS. Sometimes, outreach workers on the third floor are called down to assist in a crisis, which is why Palmer hopes that the OPS staff can add more staff positions.

While there have been two recent deaths at OPS facilities in other parts of the province, the OPS at the wellness centre has so far not lost anyone to overdose on site.

Knippshild has witnessed the rapid response by OPS staff when someone is starting to overdose.

“At the OPS, you don’t even get a chance to go a minute without breathing because there’s people always watching you,” he says. “They get oxygen on you right away, and make sure you’re sitting up, and your airway isn’t blocked.”

Tracy says she had some friends overdose last year on the street outside the wellness centre, and after someone ran up to the OPS requesting assistance, two staff members immediately ran outside and were able to save them.

“It was the care from the staff that made a difference,” Tracy says. “Street people know you can expect that from OPS because they genuinely want to see people be happy.”

At the OPS, people can also get their drugs tested. “It seems to be working really really well,” Palmer says. “People are taking the information that they’re given very seriously, and doing what’s best for them after they receive it.”

Bell says he has occasionally had his “down” tested “so you can know right then and there what you’re getting – if you’re getting ripped off or if you’re getting a good dose or just a bunch of codeine and morphine.”

Clients tout the benefits of the health clinic at the wellness centre

The clinic space at the wellness centre works a bit like a walk-in clinic, where people can receive primary care as well as safe supply and opioid agonist therapy medications. The “low-barrier” clinic is open four afternoons a week, with either an addiction medicine physician or nurse practitioner certified in addiction medicine seeing about 20 to 25 people per afternoon, Huston says. Island Health hopes the clinic will be able to expand to five days a week.

Overall, 389 people are supported by the addictions medicine providers, according to Island Health. Huston says that the incorporation of the health clinic at the centre is making a difference.

“Having people able to monitor them and support them through that process has really been hugely impactful on the folks that are accessing services and for the team members that are supporting them,” she says.

Opioid agonist treatment involves prescribing medications, such as methadone and Kadian, that are intended to prevent symptoms of opioid withdrawal and reduce cravings. The focus of safer supply is to reduce the risk of overdose by providing prescription opioids, such as hydromorphone and oxycodone, as a substitute for toxic street drugs. Many clients participate in both.

For example, Sylvester says he has a prescription of Kadian that he takes under supervision at the clinic and also receives hydromorphone and oxycodone through the safer supply program. He says that the safer supply program is a deterrent to theft.

“Without a doubt it reduces people from stealing,” he says. “It gives your life back –you won’t be stealing, you’re not in jail, you don’t have to detox in a cell or in the hospital.”

Bell recommends that everyone with a substance use problem have a maintenance plan set up with a provider. He says he has found that Methadose, a version of methadone, works best for him in preventing dope sickness. He still smokes “down” a few times a day, but way less than he would if he didn’t have Methadose. It allows him to avoid serious withdrawal symptoms if he can’t find or afford “down,” Bell says. “I can go to bed and sleep well and not have the heebie jeebies.”

Calls for expanded reach and expanded hours

![Two large poster-board signs rest against the back of a chair and on the grass. Both signs have writing on them, but the sign on the right is half-behind the sign on the left so the phrasing cannot be made out. The sign on the left reads "Did you know? The illicit drug poisoning crisis in B.C. is the leading cause of death for those aged 19-39 years. #endthestigma [Source: BCCDC 2021 using data from BC Coroner's Service and Vital Statistics]"](https://thediscourse.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/IOAD5-1-1024x683.jpg)

Palmer hopes that the wellness centre will be able to expand its clientele. The majority of toxic overdose deaths in B.C. last year, 54.6 percent, occurred in private homes, often by people using alone.

“I wish that more people that were in their own private residences would use our services more,” she says.

To better serve its existing clients, the OPS recently expanded its hours by opening two hours earlier, so it is now open from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

“We re-evaluated that because there was a need for people wanting to come in earlier and so, we were able to stretch the hours based on the staffing capacity,” Huston says.

There is a clamour among clients, and even critics of the wellness centre, to expand the OPS hours much further.

The biggest congregation outside the wellness centre occurs when the OPS closes at 7 p.m., as clients spill onto the street. “It would be nice to have a 24-hour spot because people do use 24 hours,” Sylvester explains.

Will Arnold, who owns a nearby business and opposes the wellness centre’s location, has gotten to know many of the clients over the past few years. “People are not shooting up just in the afternoons,” he says. “It needs to be open 24 hours, no question.”

Huston also supports the notion of a 24-7 OPS, but explains that there isn’t enough funding and staffing to expand the hours any further. “That’s something that we’ve definitely discussed, and it’s something that we would obviously love to be able to provide,” she says, adding that is something the provincial government is looking into.

Bell, like the other clients quoted in this story, is a peer outreach worker with the Cowichan Community Action Team. The centre might not be great for the optics of the neighbourhood, but for those on the inside, it’s a different story, he says.

“No bad can come from the wellness centre.”