This is from our Cowichan Valley weekly newsletter. You can sign up here.

Today, I’m feeling sad and angry — as a resident of the Cowichan Valley, and as a member of the media.

As the drawn-out case involving the alleged abuse of Teddy the dog — who was seized from his owners’ property on Cowichan Tribes reserve land more than one year ago — continues in Duncan court, each new development is followed by a flurry of local news coverage. This is the logic of news reporting: People get fired up about animal suffering. Give the people what they want.

But news organizations can and should consider the impact of their reporting. And in this case, the impact of intense coverage is that many in the Cowichan Tribes community say they feel unsafe in their homes, in their neighbourhoods, and out in public generally.

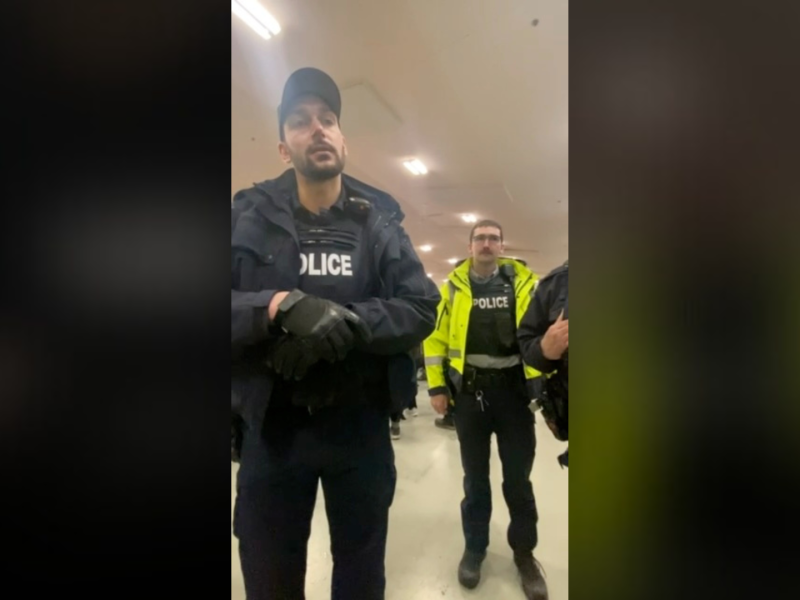

At a news conference hosted by Cowichan Tribes Wednesday morning, Chief William Seymour joined Cowichan Valley elected officials to denounce acts of vigilantism, threats against Cowichan Tribes community members, and hateful language on social media.

“When I see the kinds of things that are being done, the kind of graffiti, the kind of threats, the kind of language that’s being used, I’m aghast,” North Cowichan Mayor Al Siebring said. “Yes, we need to ratchet this down, yes we need to let the justice system do its work, but more than that, we need to stand as a community and say we live in a place that’s governed by the rule of law, not vigilantism. Not those kinds of visceral reactions.”

“Right now, what is so necessary is to remind everybody in this community that the most important thing is that, in Cowichan, we take care of each other,” said Cowichan Valley MLA Sonia Furstenau. “We don’t react in ways that create division, we react in ways rooted in kindness and compassion and empathy.”

When Teddy the dog was seized in February 2018, he was chained and emaciated, and died two days later from his injuries. More than 200,000 people signed a petition calling for the dog’s owners to receive the maximum sentence available in animal abuse cases: a $10,000 fine and time in jail. Each day the court hears the case, protesters stand outside the Round Building in Duncan with signs demanding justice for Teddy.

Last week, CTV News interviewed a neighbour of the dog’s owners saying he’s faced escalating violence and threats since the case began making headlines, including bullets fired at the side of his house last summer, and a recent grass fire that sent him to the hospital for smoke inhalation.

On its face, this report on the threats this man now faces in his home seems like a good thing: The media is using its platform to call attention to racially charged vigilantism in our community. But when the story went online, Facebook was flooded with comments calling for the prosecution of the neighbour because, the commenters assumed, he knew or should have known about the abuse, and he didn’t act or didn’t act soon enough to intervene.

What makes me even angrier about the Facebook comments on the CTV News story (the worst of which have since been taken down) is this: Here is a news organization trying to shed light on the racism now swirling around this case, and yet the outcome is more harm. First Nations members of our community have told me how terrible it makes them feel to see these comments, how it reopens old wounds and shows how far our community has yet to go when it comes to reconciliation.

“Our neighbours are reading this and are feeling a kind of terrible that is hard for me to imagine,” said Amanda Marchand, who is non-Indigenous, in a Facebook comment. “People have shared how they are being treated poorly out in the community, they are talking about how they are afraid for their children to be caught in the crossfire. They are talking about how they are afraid their pets will be stolen. Are they seeing enough of their neighbours care? No.”

Lots of people asking for justice for Teddy will tell you their concerns have nothing to do with race. But try to find a case where the alleged abusers were white, and an entire neighbourhood is asked to answer for the crime of an individual. I don’t remember protests when charges were stayed against an alleged cat abuser in Duncan last year. I don’t remember people asking for the entire neighbourhood to be held to account.

Those who are paying attention will note that Cowichan Tribes members are speaking out about animal abuse within their community, and calling on leadership to do better. They’ll notice that Cowichan Tribes has responded to these concerns with action. They’ll see that the Cowichan Tribes community is full of happy, healthy animals who are loved and cared for deeply.

Reconciliation is a journey, and many steps have already been taken here in the Cowichan Valley. Last fall, I attended Q’shintul: Walking Together, a gathering to celebrate 10 years of deliberate action bringing together Cowichan’s Indigenous and settler communities. Cowichan elders have presented The Village Workshop, an interactive learning journey about local history and reconciliation, to more than 4,000 people since 2012. (There are dates coming up on Salt Spring Island, in Mill Bay, Glenora and Saltair.)

Still, when I read the comments sections on articles about Teddy, I’m reminded that news organizations, too, have a long way to go when it comes to reconciliation. Canadian media still have a dismal record when it comes to the representation of Indigenous people. They must consider the impacts of where they focus attention and also how they moderate and participate in the public conversation.

I’ve just begun reading White Fragility, a book by white author Robin DiAngelo about her experiences leading conversations about race with largely white audiences. In the introduction, she says:

I believe that white progressives cause the most daily damage to people of colour. I define a white progressive as any white person who thinks he or she is not racist, or is less racist, or in the “choir,” or already “gets it.” White progressives can be the most difficult for people of colour because, to the degree that we think we have arrived, we will put our energy into making sure that others see us having arrived. None of our energy will go into what we need to be doing for the rest of our lives: engaging in ongoing self-awareness, continuing education, relationship building, and actual antiracist practice. White progressives do indeed uphold and perpetrate racism, but our defensiveness and certitude make it virtually impossible to explain to us how we do so.

- I’ve encountered many of this breed of white progressives in the media industry, and I include myself. It’s a tough pill to swallow. None of my “wokeness,” none of my university courses, none of my relationships with First Nations people exempt me from the work that still needs to be done. None excuse me from grappling with the reality that I live and make my living as an uninvited guest on the unceded territory of the Hul’qumi’num-speaking Coast Salish peoples.

- I’m up for the work ahead. I’m eager to listen and deepen relationships with Cowichan Valley’s many communities. I’m ready for the challenge of accepting criticism, and then learning and growing, with you — all of you — as my teachers. [end]

This is from the Cowichan Valley’s weekly newsletter. If you like what you’re reading, help grow this community by encouraging your friends to subscribe.