| 1: What happened | 2: Friends mourn | 3: Chris’s struggles | 4: Feeling better | 5: Downward spiral | 6: A mother’s loss | 7: RCMP training | 8: Not enough, some say | 9: What works? | 10: Car 60 | 11: What about Chris?

Update, Feb. 8, 2021: B.C.’s Independent Investigations Office has closed its investigation into the shooting death of Chris Bloomfield by officers with Shawnigan Lake RCMP. The IIO did not find “reasonable grounds to believe that an officer may have committed an offence” and will not refer the case to Crown council for consideration of charges against police. Here’s a link to the report.

It’s the evening of Nov. 9, 2018, and Marilyn Bloomfield is at home with her son Chris, 27, in the double-wide mobile home they share between Mill Bay and Shawnigan Lake, two small communities on southern Vancouver Island, B.C.

Chris is psychotic. It’s been days since he’s slept. He’s been taking drugs, lots of them. Cocaine, ketamine, LSD and others. “All these entities entered his body and his mind,” Marilyn recalls. “There was Satan, and Satan’s daughter Lucy, and Jesus was there, too.”

“When he was Satan, he was terrible,” she says. “He was calling me names, and telling me to ‘Do this, you effing bitch,’ and all kinds of things, when he was Satan.”

“He had all of these voices coming out of him, and I told him, ‘I can’t take that.’ I said, ‘You can stay, but they all have to leave. And if you can’t get them to leave, you all have to go. I can’t have you in here with you being like this.’

“I said, ‘If you’re going to continue like this, Chris, I’m going to call the police and have you taken to the psych ward.’ Then he pushed me against the cabinet in there and he held me down and injured my back.”

The only two times in her life when Chris assaulted her physically were after she threatened to call the police, Marilyn says. He told her he’d been roughed up by police on previous occasions, and he truly seemed to fear them.

That night, Marilyn was afraid for her safety and that of her son. She says he placed crystals on her body and talked about them ascending together to another plane. In the morning, she tried again to convince Chris to go with her to the hospital. He refused, so she said she was going to a friend’s place, and left.

Instead, Marilyn went to the RCMP detachment in Shawnigan Lake, where she told police that her son was on drugs and psychotic and needed to be taken to the hospital. She told them he had assaulted her but she wasn’t there to have him arrested or to press charges. She just wanted police to help her son get the care he clearly needed.

Outside the detachment, Marilyn says she encountered RCMP officers loading guns into their vehicles. “I asked them if they were going to go and pick up Chris Bloomfield,” she says. “And one person said, ‘No, we’re going out on a different call.’ And I said, ‘Well, if you’re going to pick up Chris, he’s psychotic, he needs some help, he needs to go to the hospital.”

A police officer asked if Chris had any martial arts training. She recalls saying no, and that he’s 145 pounds and 6’1 and doesn’t work out or lift weights. Someone asked if he had a gun, and she again said no.

“I said, ‘Just please don’t hurt him,’” Marilyn recalls. “And that’s when one of them really sarcastically said to me, ’Well that’s up to Chris, isn’t it?’”

Marilyn next drove herself to the hospital to get her back checked out. On her way home, she again stopped at the RCMP detachment. She wanted to make sure Chris had been apprehended before going home. There, police told her that her son had been shot. He was dead.

“It was one of the worst moments of my life,” Marilyn recalls. “I’ll never forget it.”

Little information is available about what happened between when police arrived at Chris’s house and when he was shot.

In a press release from Nov. 10, 2018, the RCMP says officers from the Shawinigan Lake detachment went to a home on Mill Bay Road to follow up “on an assault investigation.”

The officers arrived just after noon, the press release says, “with the intention of arresting a lone male in connection with the incident. Upon entering the residence, the officers were met with a male who they indicate advanced on them with an edged weapon.”

The officers attempted to deploy a taser “without success,” the release says. And then “shots were fired by police.”

The man was brought to hospital, where he “succumbed to his injuries,” the release says. No officers were injured in the encounter, it adds.

The Independent Investigations Office of B.C.’s chief civilian director, Ronald MacDonald, confirmed that three officers were at the scene and two were involved in the incident. The IIO is currently investigating, as it does all police-involved incidents of death or serious harm in the province.

As a result of that investigation, the IIO will either pass the matter along to Crown prosecutors to consider pressing charges against the officers involved, or recommend against charges and release a public report explaining that decision.

An RCMP spokesperson declined to comment specifically on the incident at this time because it’s under ongoing investigation.

In the days after Chris’s death, friends flocked to his Facebook page to express shock and grief. They remembered him as kind and gentle, a teacher, healer, and loving friend.

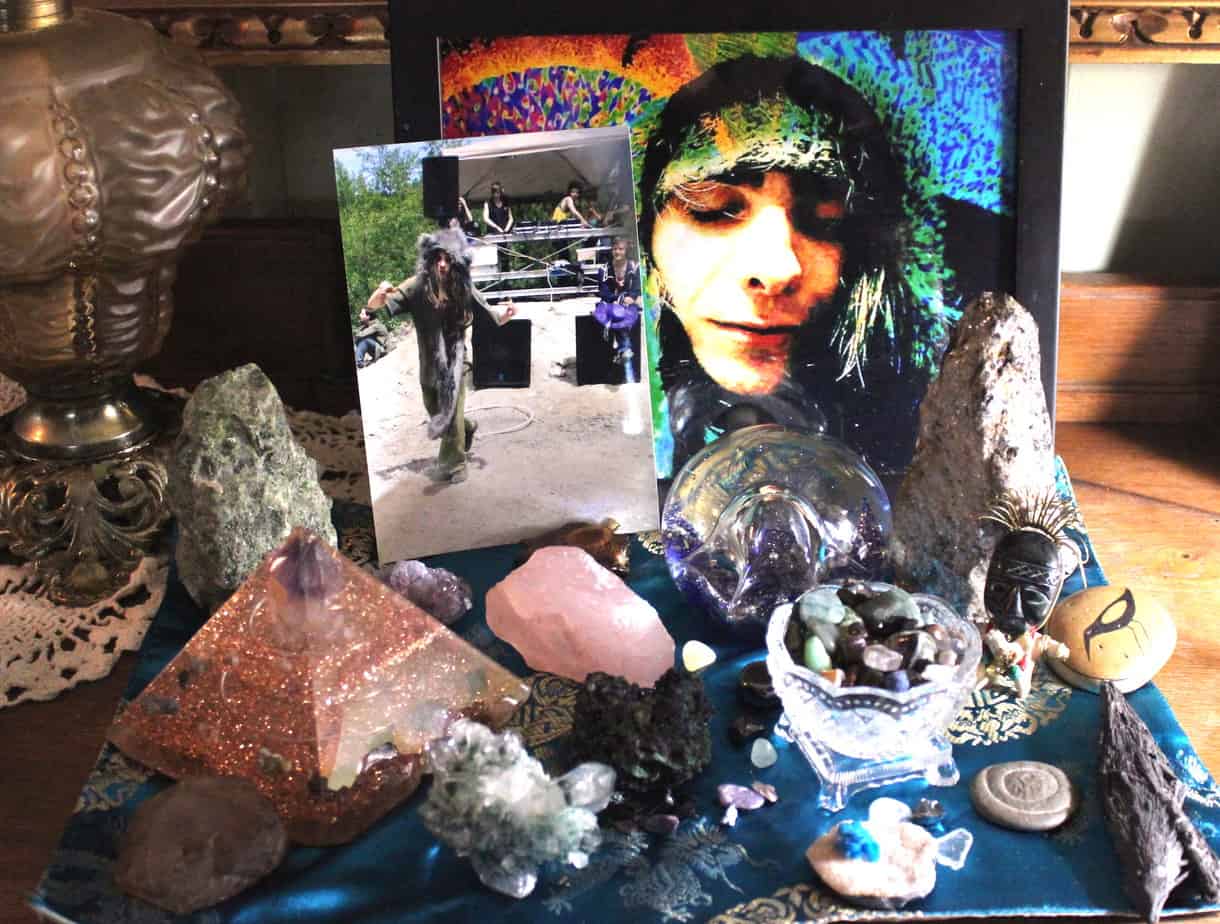

Chris had many passions in life. He loved to dance; the music would flow through him, his mom says. He was spiritual. He collected crystals and researched the medicinal properties of herbs. He explored cooking and health foods. He wanted to heal people, and he wanted to heal the world. He cared for nature and for animals. He held a special affinity for wolves.

“People really wanted that guy around,” says Kyren Teufel, one of Chris’s best friends. “He was an asset to a party, or to a hike. He was that one that was a little different from the group, but he was there and everyone was comfortable with him.”

He liked to challenge people, and open their minds to different ways of thinking. “He had such an imagination,” Teufel says. “There was so many different aspects that he wanted to bring out in himself and share with others. He was almost like a wizard, you know? He had his own way of doing things.”

Chris was also passionate about psilocybin mushrooms, which he grew and sold. He believed in the healing powers of psychedelics and considered himself a psychonaut — an explorer of different realms of consciousness. He looked up to Terence McKenna, an advocate of psychedelics and hero of the ’90s rave scene. Chris’s mom says that, when he sold drugs, they always came with a lesson on how to use them in safer ways, and he’d test them to make sure they were pure. Although she disagreed with his drug use and dealing, she says that “he felt that he was helping people.”

He ministered to the hurt and the struggling. His mom remembers him always needing to stop if he saw someone on the street who looked like they were suffering. “We’d park the car and he’d see somebody in the corner having a hard time. He’d go put his arms around them and talk to them and bless them. I’d say, ‘Chris, get back in the car!’” He’d give whatever he could — money or whatever was on hand.

His mom sometimes flips through the guest book from Chris’s celebration of life and marvels at the kind comments, at how many people felt deeply touched by her son. She reads one, from a woman who told her at the funeral that Chris helped her get completely off drugs and turn her life around:

“Chris served as the clearest mirror for me, much like the medicine he offered. He showed me exactly what I needed at any given moment. He was a true healer. Due to this I often felt a little uncomfortable around him, as his pure-hearted acceptance showed me how I lacked in such. In his honour I vow to continue to spread this seed of growth, which he saw so clearly in me, and released the shackles that I chained myself in. I shall be a blessed soul if I ever come close to emulating the love that he did and still does. Forever a part of our hearts.”

Even the friends Marilyn plays bridge with, whom she describes as straight-laced types in their 70s, seemed to really love and understand her son. One of them told her once that Chris looked quite a lot like how he pictured Jesus, she says. Another wrote in the guest book: “When you downloaded your essence into my mind, I forever knew that we were connected. I will always hold you in my heart.” Guests were invited to take home mementos from among Chris’s treasures. The friend’s message concluded: “P.S. I picked the love stone from your magic bag.”

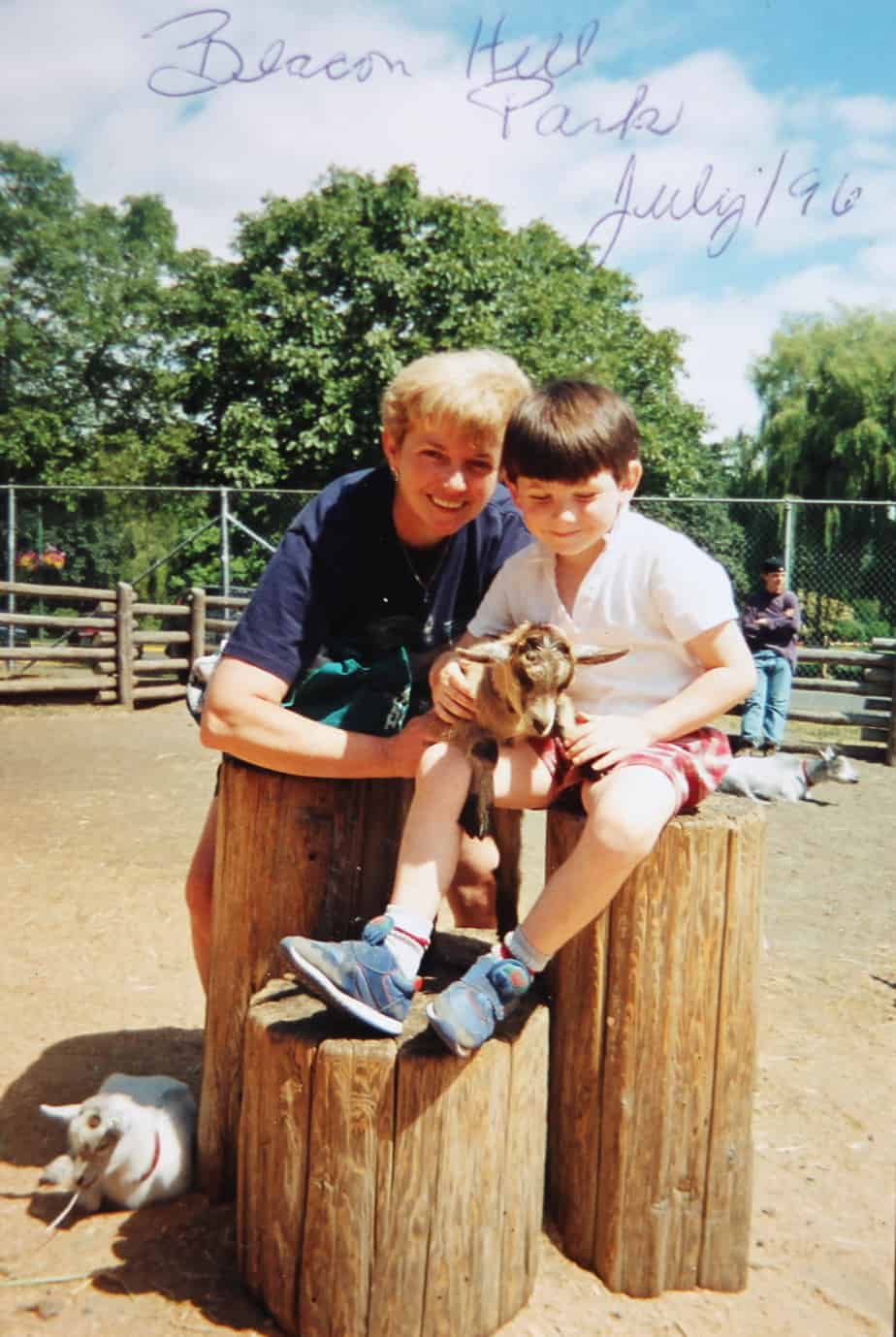

Chris struggled in his life from the very beginning. His mom says he was born with the umbilical cord around his neck, cutting off oxygen for three minutes. “He had a lot of issues as a baby,” Marilyn recalls. He suffered from asthma, ear infections and short-term memory loss.

He struggled at school. The kids picked on him, calling him a “retard;” one of the teachers called him a “retard” once, too, Marilyn recalls. “He never had that confidence that he should have had. He was very artistic, but not academic.”

Chris grew up in a stable home with loving parents, Marilyn says, and her instinct was to protect her son any way she could. After a tubal pregnancy in her early 30s, she thought she’d never have a child. She was 42 when she gave birth to Chris. “He was such a blessing, and I was so happy,” she recalls. “He was just a precious child; he really was.”

Marilyn says she did what she could to support her son, including attending middle school with him to help Chris and others in the class that had been labelled “slow learners.” But while she tried to build him up, Chris’s father often put him down, she alleges. “He thought he should buck up and be a man, that sort of thing,” Marilyn says. Chris’s father passed away seven years ago of fibrosis of the lungs, and suffered greatly in the last years of his life, she says.

By Grade 7, Chris had started smoking pot. Later it was other drugs, especially mushrooms. He ended up in hospital as a teenager, after eating poisonous mushrooms; he stayed in the mental health ward for several months, his mom recalls. He was seeing a psychiatrist weekly by the age of 15 or 16, she adds.

For a time, as a young adult, Chris lived on the streets, in squats or with a girlfriend in Vancouver but their relationship was volatile, Marilyn says. He got into methamphetamine. He wasn’t taking care of himself. His teeth were so damaged that he eventually had them replaced with dentures.

His friends back home, meanwhile, were reaching out, urging him to take care of himself, asking him to leave his girlfriend and come home, Marilyn and his friend Kyren Teufel both say. Eventually Chris’s girlfriend had him charged with assault, Marilyn says, and Chris spent a couple of months at a mental health facility and a couple more in pretrial detention.

Ultimately, he was released on probation and on the condition he return to Vancouver Island to live with his mother, Marilyn says.

Once he got home, he worked hard to get off meth, she adds. She recalls him screaming in his bedroom with the door closed. But he got through it, she says, and quit taking meth.

Chris seemed to get a whole lot better after that. “For him it was a wake-up-call,” says Teufel. “Every year, he seemed to get a little more into himself, and like, happy in himself. I saw less and less hesitance and doubts.”

From Teufel’s perspective, Chris certainly sometimes took it too far with the drugs. “He was really addicted to highs. He wanted to be high all the time, whatever it was. That was his addiction,” he says.

“Addiction’s really serious and I think Chris had a pretty addictive personality,” Teufel continues. Chris always did more, went deeper than anyone else. “There were times when I was kinda looking out for him, or just stepped back a little bit, to take care of myself. Because he would dive into something, and I might be on the sideline, and like, ’Uh, I’m not going to go there.’”

But his friend also saw Chris showing the self-awareness to pull back and recover if he went too far, as he did after leaving Vancouver. In his last years, Chris was mostly smoking weed, Teufel says; when he’d do mushrooms or another drug, he’d do so with intention. A principle in the psychedelic community is that you should pay attention to your mindset and physical surroundings when planning to use drugs to allow for a safer and more positive experience, and Chris was doing that, Teufel says. Sometimes he’d order something off the internet, and write a trip report based on his experience to share online with others in his group of psychonauts. He seemed to be doing all right, Teufel says.

“He really loved his mom, and the last three or four years, it really seemed like he was putting more thought into her future, rather than his own, even,” he says. “He was really trying to set the place up for her. He wanted to make a really nice garden and be self-sustainable. He was just looking out for her a lot. He’d mention her a lot more than in previous years, where he was probably more focused on himself.”

Just a couple of months before he died, Chris was the best Teufel had ever seen him, he says. He was more confident, and seemed to have more of a sense of direction in life.

Chris’s psychiatrist, who had been seeing him monthly, seems to have agreed. According to Marilyn, the psychiatrist released Chris from regular care just a month before he died, saying he was doing well enough to pause regular visits. Marilyn says Chris was really upset when she picked him up from his last regular appointment. He relied on his psychiatrist and hated to lose the support, she says.

It wasn’t long before Chris’s life would spiral out of control.

Sometime in October, just a few weeks before his death, Chris bought some drugs, Marilyn says. There was cocaine, and something called O-PCE — Chris’s friends later told her it was something chemically similar to PCP, or angel dust, which can be associated with hallucinations, delusions and sometimes violence. Chris’s friends told him to stay away from it, Teufel says. But Chris dove in, and he dove in hard.

The last time Teufel saw Chris, it was at a party Teufel hosted with his roommates in Duncan, near the end of October. Chris was on that drug, and he wasn’t himself. Teufel recalls talking to him for a couple of hours early the next morning, and it was a tough conversation — they both cried. Chris was bringing up stuff about the past, hard stuff about their friendship. Teufel was having a hard time getting through to Chris.

“It was like talking to someone with a disability where they can’t think properly or speak properly, and you’re trying to work with them,” he recalls. The conversation never ended right, Teufel says. He planned to talk it out with Chris another day, when Chris was sober, but he never got the chance.

Days later, Chris headed out to the Comox Valley for a Halloween party. Chris described the party in a since-deleted Facebook post on Nov. 8, 2018, two days before he died. He said he took a cocktail of drugs: mushrooms, LSD, mescaline, ketamine, DMT, O-PCE. He said the party started out well, but ended with him tied up, raped and beaten. Marilyn picked him up the next day.

It was quite clear that Chris had been traumatized, although Marilyn says she isn’t at all sure that Chris’s retelling is accurate. She says she’s since talked to someone who was at the party — someone who cared for Chris — who says that Chris was tied up because he was endangering himself and others, but no one assaulted him beyond that. Marilyn says there have been lots of times where things happened inside Chris’s head while he was psychotic, that, from her perspective, didn’t happen. Ultimately, she says, she doesn’t know exactly what happened at that party.

After the party, Chris stopped sleeping, Marilyn says. He kept using drugs. The psychosis persisted and Chris’s behaviour got worse.

Meanwhile, Chris’s friends were reaching out, especially after the Facebook post about the party. “There was so many of his friends that wanted to help him at that point in time,” Teufel says. “You think about people who have mental instability, and a lot of them actually do need help. They need people to talk to and stuff. So, for him to be killed at a time where he was really needing some help is the hardest part.”

Marilyn still lives in the mobile home park that she moved into when Chris was four, where she raised him, and where he was shot. She’s moved the furniture around a bit, and draped blankets over both of the couches to hide the spots where bullets tore through the upholstery.

Other objects are broken or missing — she’s not entirely sure what was thrown out by clean-up crews, and what was taken as evidence by investigators.

“Whether they needed to shoot him dead, I don’t know,” Marilyn says. “I have respect for the police, but I also lost my son.”

And yet she empathizes with what the officers may have gone through. “I’m sure that it was hard. It’s hard to take a life, I am sure. It’s hard to live with that, even if it is in the line of duty,” Marilyn says. “I’m sure they had many sleepless nights.”

At some point after the incident, Marilyn came home to “the hugest bouquet of flowers. Nobody would own up to them, and there was no note. I have a feeling it was a couple of the police officers,” she says.

“I don’t resent them. I don’t. I just wish it didn’t happen,” she says. “I wish the whole thing didn’t happen, but it did.”

She wasn’t there, she notes, but she thinks it’s possible that Chris came towards the officers with an edged weapon as the RCMP alleges. But he wasn’t himself in that moment, she points out. “I can imagine him running and screaming at them, and charging with a knife. I can imagine him doing that. He was not in his right mind, obviously.”

She says she hopes the laws change, so that police responding to people in a state of psychosis might have extra training or tools to deal with mental health emergencies. She particularly hopes that, in cases where the RCMP know someone is psychotic, there will always be someone on the scene who is trained specifically to deal with that.

All RCMP officers in B.C. now have to complete some mandatory training on how to deal with people in the midst of a mental health crisis.

According to a statement emailed to The Discourse by Corporal Tammy Douglas, Crisis Intervention and De-escalation Training was mandatory for all frontline police officers and their supervisors in the province by 2015. Recertification is required every three years.

The RCMP now provides this training to all its officers in B.C., Douglas says, and the mandatory recertification process is part of their Operational Skills Training. That training includes both online and “scenario-based” components, which “specifically includes a mental health-related incident,” Douglas says.

A 2014 report by the Mental Health Commission of Canada says all police forces in B.C. began training their new police officer candidates in January 2012, as well as existing first responder police officers and frontline police supervisors. “As time goes on, an increasing number of officers will have completed the training at the academy level, and will only be participating in the mandatory every-three-years requalification aspect of the program,” the report noted five years ago.

The mandatory province-wide training program, which the report says was developed by police personnel with contributions from “mental health professionals, health services and mental health agencies … and people living with mental illnesses,” includes a three-to-four-hour online course, as well as seven hours of in-person training in class and through role-playing exercises.

The online sessions cover specific mental illnesses and their symptoms, as well as techniques for de-escalation, which the Mental Health Commission defines as using verbal and non-verbal communication to bring the level of tension in a situation down. Although de-escalation is a component of police training generally, this training specifically focuses on techniques and strategies when approaching someone in emotional distress.

The 2014 report reviewed police training in mental health across Canada after seeing “a significant increase” in the number of interactions between police and people in mental health crisis — and rising concern over potential negative outcomes of these interactions, including deaths. It called B.C.’s training arguably “one of the most advanced and promising programs.”

Even before this crisis intervention training became mandatory in B.C., the RCMP revised its own general use-of-force training and policies in 2007 to emphasize “de-escalation and communication,” Douglas wrote in her email.

Recertification in the Incident Management/Intervention Model is required every year for all RCMP officers across Canada, she says. The model is designed to give officers the tools they need to assess risk in different situations — and make decisions on the level of force required.

According to the model, police may use “lethal force” only when someone presents a threat of “grievous bodily harm or death.” In all cases, officers are expected to “assess and manage risk through justifiable and reasonable intervention.” Any police intervention will be “measured against what a reasonable, trained, prudent police officer would do faced with a similar set of circumstances,” according to the RCMP’s description of the model.

According to a 2013 article in the Toronto Star and similar accounts from the U.S., police officers are not trained to shoot to wound by, say, aiming for an arm or a leg. They are trained to shoot at the chest — the easiest target — and keep shooting until the threat is no longer a threat.

“Incidents involving police use of force are complex, dynamic and constantly evolving, oftentimes in a highly-charged atmosphere. Police officers must make split-second decisions when it comes to use of force,” Douglas wrote in her email to The Discourse.

“The RCMP is continually assessing its training, and in BC has created a committee of its Mental Health Liaison Officers to help improve the present Crisis Intervention and De-escalation course,” she continued.

The RCMP also participates in several committees and studies, she noted, including a Simon Fraser University study on the impact “of persons with mental health issues on front line policing services.”

In remote communities, RCMP officers in B.C. “must draw upon their experience and training alongside other community resources, such as nurses, physicians, family and friends” to connect people in need with health care services, she added.

“Our police officers frequently go above and beyond what is expected of them in these situations, taking extra care and time to build relationships with people who suffer frequent mental health crises in their communities,” Douglas said.

Some police watchdogs say the current training isn’t good enough, and it just isn’t working.

“The sheer fact that people continue to be shot and killed by police while in the midst of a mental health crisis is obvious evidence that we need to find a better solution,” says Douglas King, the executive director of the Together Against Poverty Society in Victoria. King previously worked as the police accountability lawyer with the Pivot Legal Society in Vancouver.

“The hope was, for many years, that if every officer was trained in crisis de-escalation training, you’d start to see a decrease in these incidents, you’d start to see them in a different light, or they’d start to unravel differently when they occurred,” says King.

“Despite that shift, in adding on secondary training, it hasn’t had the intended result. We haven’t necessarily seen a fundamental change in how these interactions occur. The number of police-involved shootings has not gone down,” he says. “It doesn’t seem to be working. And for me, I think that’s an indication that secondary training is still not overriding the primary training.”

A CBC investigation counted 461 fatal encounters with police between 2000 and 2017 — more than 70 per cent of the victims suffered from mental health or substance use issues.

The investigation also found the number of fatal encounters with police is climbing. “Even when adjusted for population growth over the 17-year window, the number of people dying in encounters with police has increased steadily,” reporters Jacques Marcoux and Katie Nicholson wrote.

“The challenge with use of force policies is that they do not acknowledge the distinction between interventions with persons who do not exhibit mental illness and/or concurrent disorders and with those who do,” according to a 2008 policy statement from the Canadian Mental Health Association.

What might be an appropriate intervention for police dealing with normal resistance and aggression, may not be appropriate for dealing with people in mental health distress, the report suggests. “For example a person experiencing hallucinations and/or delusions may well exhibit active resistance or signs of aggression in response to police commands or physical control out of very real fear; applying usual police command and control tactics can escalate the fear and the crisis reaction.”

“The crime response is almost the opposite of what needs to happen in a mental health situation,” says Camia Weaver, who authored that policy statement and was at the time the justice advisor to the Canadian Mental Health Association.

“Police are geared towards getting this done fast, using authority — generally — to control a situation, and getting things wrapped up as quickly as possible, and moving along to the next thing, which can be very harmful in a mental health situation,” Weaver says.

“People, if they’ve had previous experiences with police that were not good, that’s a real problem,” she continues, “and approaching in that way can also be frightening and can be seen as being antagonistic or aggressive.”

Effective crisis intervention requires not being authoritarian, and instead taking time, having patience, and working towards collaborative solutions with the individual, Weaver says. “It’s a very different approach that most police officers are not used to, are not properly trained for.”

Weaver says she’s not impressed with the progress of police forces on this issue to date. “I don’t think we’re doing a great job in Canada, to be honest. I don’t think there is sufficient focus on dealing with these situations in the most effective way. There isn’t really an appetite for it.”

“This situation in Shawnigan Lake is another example of one where they say the police officers went into the home and the person had an edged weapon and advanced on them,” King says.

“And again, that’s the mathematical equation — A plus B equals C — edged weapon, physical movement towards the officer, they will get shot. The police just need to start really thinking about ways that they can break that cycle.”

In Canada and around the world, police departments are considering and using different approaches. In the United Kingdom, police earned praise in 2016 for a viral video showing cops disarming a man aggressively wielding a machete. Despite several advances on police with the weapon, no shots were fired. Eventually, more police arrived and surrounded the man, protecting themselves with shields. In the U.K. most frontline police officers don’t carry a firearm at all.

Weaver is now a sessional instructor at the University of the Fraser Valley in B.C., and last year submitted a master’s thesis comparing different strategies for police response to mental health crises.

“What I have seen work the best is the Crisis Intervention Team model, which has a selected and highly trained core of officers whose primary role is to respond to mental health issues in the community,” she says.

That model, also known as the Memphis Model, is now used in police forces in 49 out of 50 states in the U.S., and in four countries, according to its own website. But many police forces say they’re using a crisis-intervention model when, in fact, it does not fulfill the requirements to fully qualify, says Weaver. She says she’s not aware of any Canadian police forces that have fully adopted the model.

The idea is to train at least 20 per cent of a police force as mental health crisis intervention specialists through an intensive 40-hour training program. Then, as experts in this area for their detachments, the officers are called on to respond to people in crisis, giving them ample opportunities to practice and expand their skills and get to know individuals who regularly require this type of service, Weaver says.

They’re meant to work as a team, sharing knowledge and skills, and coordinating with other service providers in the community. Ideally, these crisis intervention specialists are available around the clock to respond in an emergency and be a resource for other officers, she adds.

There are limitations to this model, particularly in a small place like Shawnigan Lake, which as of 2016 had 11 officers in its detachment. In small detachments it can be hard to achieve 24/7 coverage of trained officers, Weaver says.

But the model can still be applied, she says. It just relies to a greater degree on coordination with neighbouring detachments and related service providers in the community. “You can have a partnership that is community-based that provides sufficient support and coverage to make sure that everything that needs to happen happens.”

King, of the Together Against Poverty Society, suggests there are advantages to working in a small community, too. “In small areas it is actually relatively easy to get to know everybody in your community, and to know who has mental health issues, to know who has the propensity to potentially be involved in this kind of situation,” he says.

All it takes is a little creativity to think about heading a risky situation off at the pass, he says. Other community resources, including local mental health professionals and social workers and people with a relationship with the individual in crisis, can also be called upon to help respond, he notes. “So in a crisis scenario, the police officer can confidently draw back and say, ‘I’m going to get this person for you to talk to, let’s work this out.’ That in itself can be a hugely de-escalating tactic.”

Alternatives to police intervention are needed, too, says King.

“There’s an inherent problem with having police be involved with de-escalation,” he says, “and one reason that police can be ineffective at de-escalating is that their presence in itself is a form of escalation.”

At the larger Duncan/North Cowichan detachment next to Shawnigan Lake, the RCMP are trying to respond differently. About two years ago, in response to a marked increase in calls for mental health interventions, the detachment partnered with the Vancouver Island Health Authority to pair up police officers and mental health nurses to respond to people in need.

“The benefits to it are huge, really, when you think of it, because the nurse is bringing a completely different perspective than a police officer, and vice versa,” says Staff Sergeant Chris Swain, a supervisor of the Car 60 program.

For one day a week, the officer and nurse work together for a full daytime shift. They maintain a list of clients who have been referred to the program, and they actively go out and check on them, assess them and connect them with services as required. The team patrols areas where more of their clients tend to be: the homeless camps, the shelters, the food bank.

In addition to the weekly patrol shift, a mental health nurse is available on call, weekdays during daytime hours, to jump in with an officer and respond to someone in crisis. (Though the RCMP won’t send the nurse into a crisis situation where the risk is deemed too high.)

“What I’ve seen is a relationship building, or a trust-building, between the clients and the team,” Swain says. “When we talk to the community, and we talk to the clients and community members, they all think it’s great. They love the program.”

Swain says he doesn’t have statistics on hand that demonstrate the program’s effectiveness. But anecdotally, he’s seen it working, both in terms of building relationships in the community and outcomes for individuals. He says he can think of at least one or two individuals who have gone from frequently needing police intervention to rarely or not at all, since connecting with the program.

“I think we can learn from VIHA [Vancouver Island Health Authority] and the crisis nurses, that everyone’s got a story, a little bit more about that person and a little bit of background,” he says.

In addition to the two or three officers who regularly work on the Car 60 team, officers not assigned to the program have opportunities to learn from the team and its nurses, too. “We’ve all been on calls where the Car 60 program and the nurses are attending,” Swain says. “Now we go on calls and we maybe ask some of the questions the nurse might ask, or try and obtain that information in another means, to help us form some sort of assessment or decision for that person. I think that would be beneficial for sure, rather than just that black-and-white, ’Okay you’re this, now we’re doing this.’”

Working with the Car 60 program is an opportunity for officers to reinforce the de-escalation skills learned in training, Swain notes. “We have our training in it, but training’s training. It’s done online, or you’ve done it in scenarios, and a lot of people are learning in real time,” he says. “And they’ll learn from their mistakes, but I think for the most part we’re doing an okay job with that, in the de-escalation portion.”

A similar model is being used in several communities in B.C., including Kelowna, Kamloops, Prince George and Surrey, Swain notes, though the programs operate independently.

It’s impossible to say what additional training, resources, strategies or skills might have changed the outcome for Chris Bloomfield.

His mom says she understands the actions the police took, but believes it could have gone another way. “I don’t think they needed to kill him. I really don’t. Honestly, I don’t think they needed to kill him.”

She hates to think of her son stuck in a mental health ward or in jail, maybe injured. He hated being restrained, hated being poked with needles and injected with drugs he didn’t consent to, she says. He’d probably opt for death over that, Marilyn speculates. But she still just wants her son back.

“I miss him so much. I wish I could hold him and I wish he could be here.”

“Part of me is gone and will always be gone, because I’ll never, ever, ever, stop missing him. He was my only child. To lose him like that, it wasn’t fair. It wasn’t fair. I didn’t want my son to be killed. I miss him so much. I wish I could have him back.”

Chris’s friend Kyren Teufel is less understanding of the police officers involved.

“The fact that the IIO [Independent Investigations Office] is even investigating is kind of ridiculous to me,” he says. “If I was the leader of the police force, I would have been like, ‘Yeah, you did something wrong. You walked into his home and killed him.’”

“I do kinda just hope that maybe — it’s very unlikely, but — I wonder if it could be a case that maybe someone higher up there in the police force might look at these sort of things and reconsider ways of approaching,” he continues.

“It’s just too bad, because we lost a really awesome person,” he says. “Nothing we can do now, but look back and maybe stop ourselves from hurting each other any more.” [end]

Cowichan Hospice Society offers support to people grieving the death of a loved one in the Cowichan region. The Vancouver Island Crisis Line can be reached 24/7 at 1-888-494-3888. A list of Canada-wide resources for those in crisis can be found here.

[cta]

How can we better support people in mental health distress?

We want to hear from you. Email Jacqueline Ronson.

[/cta]

Illustrations for this story were created by Indiana Joel. It was edited by Robin Perelle, produced by Lauren Kaljur and fact-checked by Collins Maina. Reporter Jacqueline Ronson developed the story as part of a series examining mental health and addiction issues in the Cowichan Valley. To follow Jacqueline Ronson’s reporting subscribe to her newsletter here.

[factbox]

More from this series:

Who’s struggling in the Cowichan Valley?

I asked you about your daily struggles. Here’s what you said.

Demand for mental health support increasing among Cowichan youth

Police in Cowichan respond to a growing mental health crisis

[/factbox]