Content Warning: This story mentions violence and substance use. Please read with care. To connect with your local mental health or substance use centre, call 310-MHSU (6478)

Unhoused Duncan residents and advocates are criticizing recent rhetoric that implies they’re causing more crime in the community.

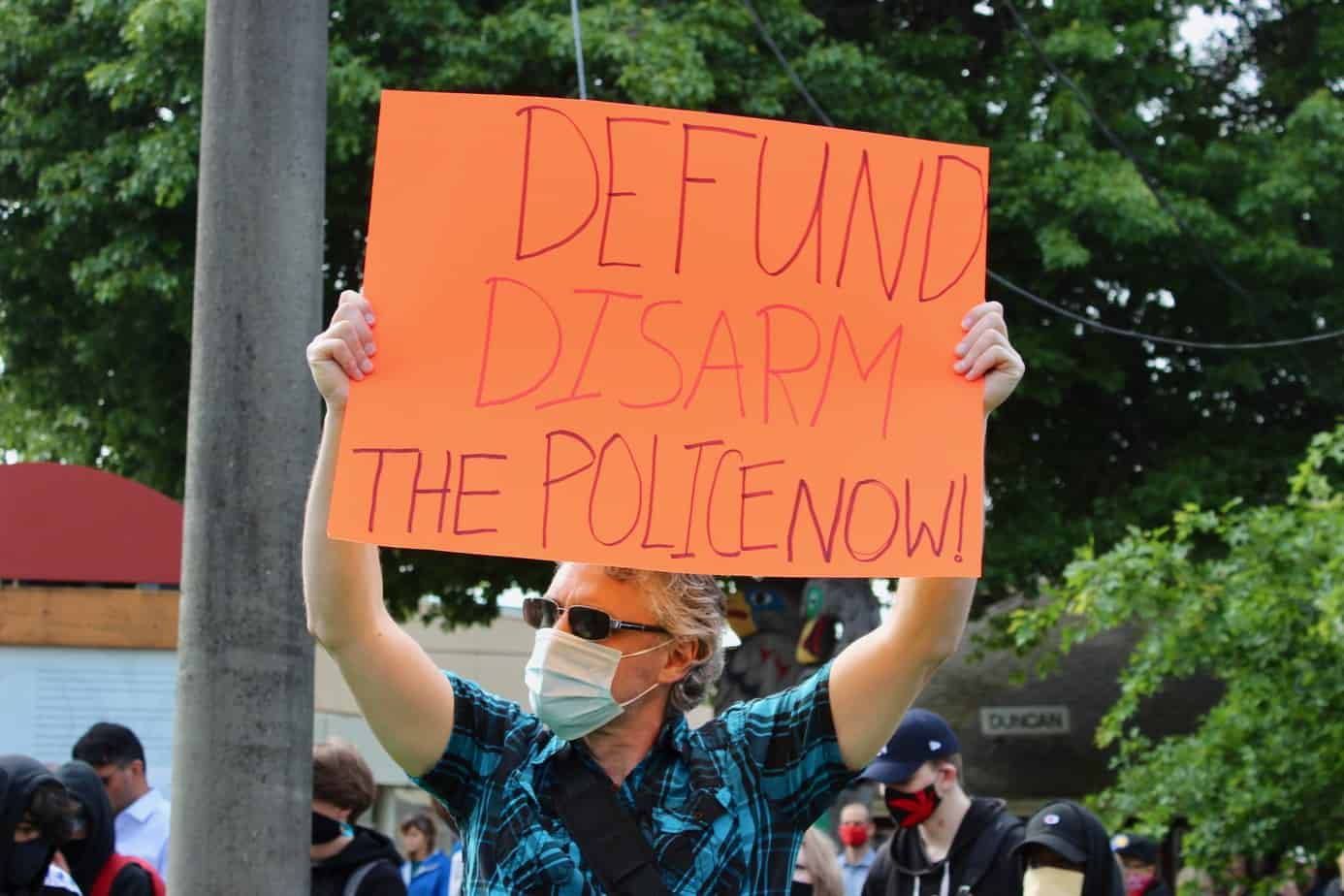

Some are speaking out after a rally on Feb. 21 saw dozens of protestors gather along Canada Avenue in Duncan carrying signs that read, “Enough is enough,” “End catch and release,” and “Charge shoplifters.”

Speakers at the rally called on the provincial and federal governments to implement harsher punishments for criminals, as well as to force substance users into involuntary treatment, and to end what they described as “catch-and-release” bail policies.

The alleged criminals decried by the protestors were community members living on the streets — unhoused and often struggling with substance use disorders.

Protestors assembled opposite Hank’s Handimart. The store’s owner, James Kim, was severely beaten on Feb. 11 while trying to stop two alleged shoplifters. He was taken to hospital with multiple injuries.

“Empower the RCMP, empower the courts,” rally organizer Travis Rankin told attendees, claiming that crime is escalating at an unprecedented rate in Duncan.

“Their policies are failing us,” he added. “Their catch-and-release protocols enable criminals.”

The crowd also cheered for Kevan Shaw, with the Nanaimo Area Public Safety Association, when he called for “mandatory involuntary care” for people who “do not want to go into housing.”

‘Forced abstinence and incarceration’

But not all community members agree with the rally’s demands. Local organization North Cowichan Cop Watch called out the protest organizers for what they called “ill-informed opinions,” fear-mongering, and spreading disinformation.

“Forced abstinence and incarceration is a tactic used by those who wish to temporarily avoid doing the crucial work of undoing decades of horrific policy on housing and drug use,” the organization said in a statement.

And while the group acknowledged the frustrations voiced by local businesses about vandalism and theft, they argued the community can support business owners “without throwing every unhoused neighbour and drug user under the bus in the name of safety.”

Read more: Fact checking claims about recovery: Substance use stigma

North Cowichan Cop Watch said rally speakers’ proposals to stop crime were not based on actual evidence.

Instead, the groups said, such rhetoric diverts attention away from the root causes of these issues — a shortage of permanent shelter beds, and a lack of necessary supports and services to meet the complex needs of people living on the streets or using drugs.

The rally did not include any speakers who are currently unhoused or use drugs, nor did it include their perspectives.

Rising violence against unhoused community members

But recent data from the RCMP actually shows a decline in property crime in Duncan and North Cowichan.

On the other hand, community members have reported an increase in violence against unhoused people.

Several studies also back up these reports, suggesting people experiencing homelessness are significantly more likely to be victims of crime compared to the housed population.

Anti-homeless attacks and hate crimes continue to be reported across Canada.

Phil, an unhoused man living at the Warmland Shelter House on Lewis Street, said violence against fellow unhoused peers is not uncommon in the area. (The Discourse is identifying him only by his first name to protect his safety).

He’s witnessed friends shot at with pellet guns, hit by vehicles, and pelted with rocks from passing vehicles.

But even when such attacks are reported to authorities, he said nothing changes.

“The cops won’t do anything,” he told The Discourse in an interview. “We know who [the attackers] are — we can point them out — and they won’t do a damn thing.”

He feels that attacks on the people in the Lewis Street area are specifically targeted at unhoused people. And the next time he’s threatened, Phil fears his only option will be to defend himself.

“What are we supposed to do?” Phil asked. “Our lives are in danger … So we have to take it to ourselves, to protect ourselves.”

Who is more likely to experience violence on the street?

Late one evening in January, two pedestrians were injured in a hit-and-run at the intersection of York Road and Lewis Street.

A worker at Warmland Shelter — who The Discourse is not identifying out of concern for their employment — described the incident as shocking.

The employee was performing a wellness check on someone when they heard screeching tires and screaming from the nearby intersection.

“I went to go see what’s going on, and I saw all the people there all gathered around on Lewis Street,” the worker recalled. “And I thought, ‘Oh my god, what if [the driver] just goes and takes them all out?’”

The incident saw a cyclist and a pedestrian hit; both went to hospital, reportedly with broken bones. But after hitting them, the driver of the vehicle continued driving erratically on York Street, the witness said, before speeding away.

The shelter employee immediately thought of the 1975 dystopian road-racing film Death Race 2000, a violent science fiction movie in which, “If you hit people, you get points from it,” said the worker.

Attacks on unhoused people likely under-reported

Attacks on unhoused people are also likely under-reported, however, because distrust of police often leads them not to call law enforcement when crimes are committed against them.

Those were the findings of a University of Ottawa study in 2008, which found unhoused people less likely to report crimes, whether as victims or witnesses, because of negative experiences with police.

Harsh responses from police can further stigmatize people who are already victims of violence and abuse, without addressing their underlying needs.

The problem is not just in Canada. Last year, the U.S. National Health Care for the Homeless Council surveyed more than 500 people experiencing homelessness in five U.S. cities.

Of unhoused respondents who said they’d experienced violence, the organization found 30 per cent believed their attacker was housed — and of those, a quarter were allegedly police officers.

The problem is compounded by what advocates say are prevalent but inaccurate stereotypes of mental health issues and substance use causing violent behaviour.

In fact people with such disorders commit a comparatively low number of violent crimes — and are much more likely to be victims of violence.

The Nanaimo-based advocacy group Stop the Sweeps collected first-hand accounts from social service non-profit workers, drug users, and unhoused people about their experiences with the RCMP.

Respondents alleged officers committed physical assaults, and used coercive tactics to search and seize unhoused residents’ personal belongings.

RCMP cites ‘risky lifestyle’ of unhoused residents

In a statement to The Discourse, RCMP spokesperson Corp. Alex Bérubé said North Cowichan/Duncan detachment officers have not seen a “noticeable uptick in violence” against unhoused people.

“We are alive to the risky lifestyle these individuals may be living,” he said, “and encourage anyone who are victims of crime or note any suspicious activity to contact police right away.”

Unhoused people are not a protected class in Canada. That means they lack the same legal protections as those from other marginalized or vulnerable demographics.

By not being specifically protected, advocates say hate crimes against unhoused people are too often ignored.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission argues that anti-homeless violence should be classified as a hate crime to protect their human rights.

And the B.C. Office of the Human Rights Commissioner has similarly called for the term “social condition” to be added to the B.C. Human Rights Code.

Such a move would give people facing discrimination based on housing status some legal recourse, but falls short of defining violence against unhoused people as a hate crime.

Crime language can harm marginalized communities

Buzzwords used by Duncan rally attendees on their signs and in speeches — such as “catch and release” and “repeat offenders” — are nothing new in the province’s political landscape.

Such rhetoric and concerns featured heavily in the B.C. Conservative Party’s public safety plan unveiled in the last provincial election.

The B.C. New Democrat government itself has discussed at length the idea of managing so-called “prolific offenders.”

A 2022 provincial report on repeat offenders in B.C. made 28 recommendations, one of which was to bring back its prolific offender management program.

In echoing such rhetoric, advocates say, the province ignores the underlying inequalities, and exacerbates anti-Indigenous racism because Indigenous people are far overrepresented in the justice system.

Indigenous people make up 36 per cent of the B.C. Corrections system, despite only representing six per cent of the province’s adult population.

The federal government has noted this overrepresentation of Indigenous people in Canada’s federal prison system too, concluding from its own research that Indigenous populations are simultaneously over- and under- policed.

Indigenous communities report being often aggressively policed, while at the same time say violations of their collective rights or calls for help are ignored by law enforcement compared to complaints by non-Indigenous people.

The Discourse is not aware of race or racism being mentioned at last month’s public safety protest. But advocates say harsher punishments for offenders would affect a disproportionate number of Indigenous people and other racialized groups, who come into contact with police at higher rates than the rest of the population.

Pivot Legal Society criticized the province’s 2022 crime study for not defining the term “prolific offenders,” and for conflating crimes committed by people with substance use and mental health disorders with random acts of violence.

Is more involuntary care the solution?

Across the province, 70 facilities already accept involuntary patients under current B.C. mental health laws, but adults still have the right to refuse treatment, even if their refusal could result in death.

“We cannot compel people into healing from this disorder, any more than we can force someone with a different diagnosis into treatment,” said Megan Worley, executive director of VisionQuest Society, in an interview with The Discourse’s Kamloops publication The Wren. “It simply doesn’t work.”

Roughly 20,000 people are already held involuntarily under the B.C. Mental Health Act each year.

Yet evidence suggests that forced treatment has not been shown to be more effective than voluntary care.

And in some cases, experts warn it can even increase the risk of someone overdosing when they are released from custody.

The Canadian Mental Health Association is worried that detaining more people in current facilities without addressing the quality and effectiveness of care won’t have positive outcomes for the people who need it.

Read More: Fact-checking claims about recovery: Involuntary treatment

But even if there were a way to expand involuntary care effectively, many experts and advocates doubt the healthcare system could handle the increase in patients — when it already often doesn’t have enough beds for those who actually want help.

Who feels ‘safer’ with more police?

The B.C. Coroner’s Service reported a 23 per cent rise in deaths of unhoused people in 2023 compared to the previous year.

Central Vancouver Island, which includes the Cowichan Valley and Nanaimo, saw the second-highest number of unhoused residents’ deaths in B.C., eclipsed only by Vancouver.

That Coroner’s report noted the mortality rate should be interpreted with caution, as it excluded unhoused people’s deaths that did not meet the legal criteria for investigation under the Coroners Act.

Speakers at the Duncan rally not only focused on policies experts said are either ineffective or cause more harm to already marginalized communities.

Additionally, the protest’s calls to empower law enforcement and increase police presence came as police budgets have increased across the country by over three per cent every year since 2020.

The Municipality of North Cowichan budgeted $910,000 more on policing this year than last year, yet the RCMP wants more resources to address crime in the region.

So who feels more safe when there are more police around? Depending on who you ask, the answer varies. Factors such as age, race, and what community people belong to often shape how they perceive police.

For legal advocates with Pivot Legal Society, police funding should be reduced — not boosted — and instead governments should invest more in community-led responses to harm.

That echoes the calls by Stop the Sweeps for permanent funding for drug user-led groups such as the Nanaimo Area Network of Drug Users.

Read More: Fact checking claims about NANDU and peer-run safe consumption sites

The CMHA argues the province should keep investing in mental health supports, or risk losing momentum since it promised major investments after the B.C. NDP came to power in 2017.

Federal Housing Advocate Marie-Josée Houle told The Discourse her reviews of encampments found those experiencing homelessness repeatedly said they don’t have access to supportive housing or support for addictions.

Rather than criminalizing people “facing disadvantage,” she believes that “decision-makers must address the root causes of homelessness and addictions,” including poverty, no housing options, and inadequate healthcare.

“Criminalizing people experiencing homelessness doesn’t work,” Houle said. “Providing a permanent, safe and secure place to call home with supports will.”

For Phil, at Warmland shelter, he hopes other city residents can take time to learn more about what it’s actually like to be homeless, and said he is planning a film about life as an unhoused person.

“I want to make it so that we tell the story of what happened out here,” he told The Discourse. “So people can also tell their story … how they got here.

“This could really kind of wake people up.”