This analysis won gold for Best Column in the 2024 Canadian Online Publishing Awards.

Two weeks ago, community members in the Cowichan Valley gathered for a rally that called on governments at all levels to address homelessness and drug use in the communities. The event took place on York Road in Duncan and was organized by a group called the Canadian Citizens Against Crime and Public Drug Use.

The Discourse has been covering issues of homelessness and the toxic drug crisis for years, and the consensus seems to be the same from all community members: the situation is out of hand. There have been more toxic drug deaths than ever before, and as inflation and cost of living rise — combined with a housing crisis — more people are losing their housing. But people are divided on how to find solutions to these issues.

On the one hand, some groups paint people who use drugs and people experiencing homelessness as criminals who need to be institutionalized, forced into treatment or put in jail. This sentiment was strongly represented at the recent rally.

“If I were in their shoes, I would hope to God somebody would have the common sense to put me in jail or some kind of institution so that I might have a chance at life,” one speaker at the rally said as the crowd encouraged him.

“Use the Mental Health Act to place those doing harm to themselves into complex care,” said rally organizer Travis Rankin in a speech. “Place criminals in jail. If they need deeper help, provide it.”

But those calls are a far cry from what most experts see as the evidence-based solutions that are likely to save lives and move people towards increased stability and wellness: supportive housing, voluntary treatment, harm reduction and access to a safe supply for those at risk of overdose death.

Recently, I spoke with Cindy Lise, Cowichan Communities Health Network regional coordinator, who has been involved in this project as well as many others addressing homelessness and the toxic drug crisis in Cowichan. She said something that stuck with me.

She doesn’t want to draw a line that divides people who are angry and calling for change, she said, “because everybody is fighting for their community in the way they see is best.”

That was clear at the rally, where people called for “care and compassion” with shouts of “enough is enough.”

“I care as much for our community and how to get us to wellness as somebody who has a totally different approach,” Lise said. “Our challenge as a community is, how can we do that together?”

I’m left mulling the question. If people agree on the destination but not on the path forward, where do we go from here?

How did we get here?

At the rally on York Road, some folks made statements suggesting the issue of increased homelessness and public drug use is a recent one. The argument seems to be that recent responses to address the issue, particularly drug decriminalization and safe supply, are making the problem worse instead of better.

It’s undeniable that these issues are on the rise. But the roots of the problem run deep — and are enormous in the face of recent and limited interventions to blunt some of the most acute harm.

Social housing and rental building construction slowed down significantly in the 1990s and 2000s. The federal government in the 1980s and 1990s withdrew from housing, reducing tax breaks and incentives to develop purpose-built rentals and social housing. Meanwhile developers began building more lucrative developments, such as condos. This article from The Tyee sums it up pretty well. Social housing developments seemed to fall off a cliff starting in the mid-1990s, and still haven’t bounced back.

The 2021 Cowichan Valley Regional District Housing Needs Assessment summarizes that there is an “acute need for housing and services for unhoused individuals and those engaged in substance misuse.” In other words, social and supportive housing.

Affordable housing is also difficult to find in the region, putting young families, low-income families, lone parent families and seniors at risk of housing instability. Results from the 2023 Point in Time count tell us that the demographic of people who are unhoused is becoming more diverse as we start to see more seniors, youth and families lose their housing because they can’t find an affordable place to live.

The report also says there is an “acute shortage of rental housing” in the region, with almost no vacancy for rentals that meet the needs of families. Meanwhile, the Cowichan Valley’s population continues to grow and continues to age.

The roots of the toxic drug crisis are deep and complex, and don’t lend themselves to an easy summary. People use substances, both regulated and unregulated, for all kinds of reasons, and most do so without deadly or life-altering consequences.

But part of the story of how we got here occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, when prescription opioids were regularly prescribed by doctors. This continued for years, with over 20 million prescriptions for opioids dispensed in Canada in 2016 — nearly one prescription for every person over the age of 18 according to a 2018 study from Canada’s Public Health Agency. The study found that unprescribed use of opioids began increasing in 1999 as people shared them with family and friends, committed prescription fraud and forgery and turned to street drug markets.

![Two poster boards lean against a chair on the grass, with one of them partially covering the one behind it. The one in full view reads: "Did you know? The illicit drug poisoning crisis in B.C. is the leading cause of death for those aged 19-39 years. #endthestigma. [Source: BCCDC 2021 using data from BC Coroner's Service and Vital Statistics]](https://thediscourse.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/IOAD5-1-1024x683.jpg)

As more people sought out opioids from street dealers, those manufacturing the illicit drugs found an economic incentive to create and sell more potent opioids. This has been described as the iron law of prohibition — when a substance is prohibited, the illicit market will produce it in increasingly potent and toxic forms. Fentanyl and its analogues became more commonly found on the streets, increasing risk for drug toxicity and overdose.

By 2017, fentanyl or an analogue of it was found in more than 50 per cent of heroin samples tested by Health Canada’s Drug Analysis Service, and it was found in samples of methamphetamines and cocaine as well.

One year prior to that, the province of B.C. declared a public health emergency in response to increasing opioid-related overdose deaths due to drug poisoning. That same year, a group of community partners in the Cowichan Valley who supported people with mental health and addictions published a Sobering and Detox report and presented it to the CVRD and BC Coroner’s Service. The report identified that substance use challenges in the community were present and growing, and there weren’t enough resources available to support people.

And that’s still the case. It’s undeniable that homelessness and drug use are linked. Those who are on the streets turn to substances to make living in vulnerable, dangerous situations more bearable. And people who become addicted to substances — for reasons that are often linked to mental health — risk losing housing for myriad reasons including loss of support, family, employment and more.

Needless to say, this issue didn’t just happen overnight. Nor did it pop up in recent years. It’s been building for decades, and inaction over those decades has put us in the situation we’re in today.

Does imprisonment and forced treatment work?

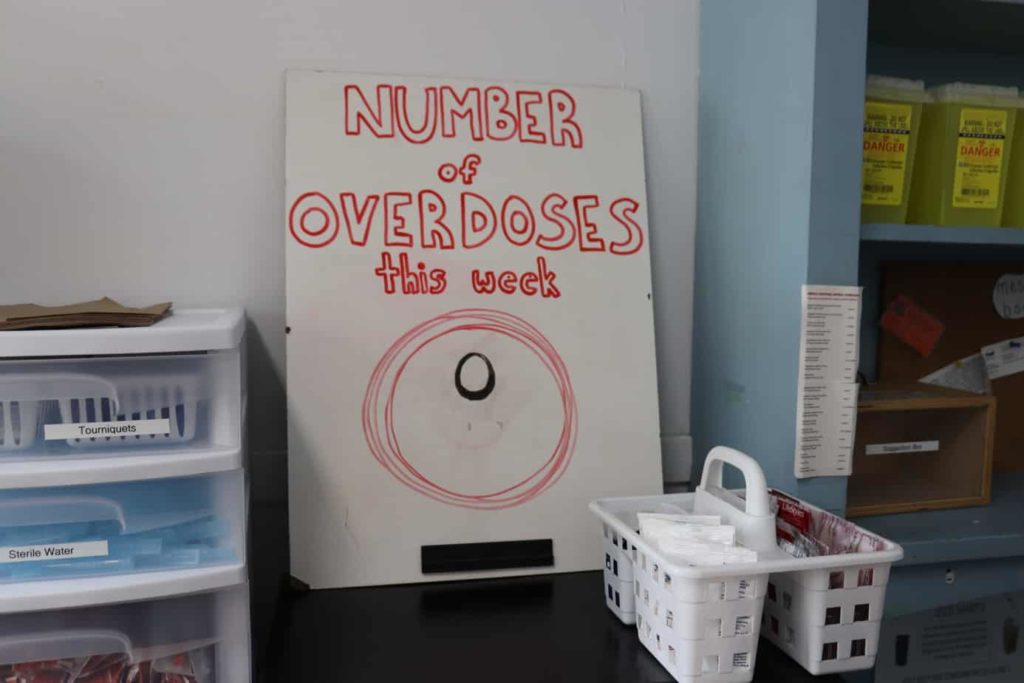

Many people at the rally on York Road were seen holding signs advocating for sending people to jail. They called for repealing drug decriminalization and pushing people who use drugs into treatment. Speakers were heard questioning if safe supply and overdose prevention sites work, and a person in the crowd likened “free drugs” to “free suicide.” Speakers aligned increasing toxic drug deaths with the availability of safe supply.

But evidence shows that’s not true.

Safe supply isn’t easy to access. An estimated 100,000 people in B.C. have an opioid use disorder, and only about 5,000 of them have access to a prescribed safe supply. But for those with access, research suggests that it does more good than harm.

Evidence shows that prescribed safe supply does not contribute to drug-related deaths, and that the risk of death and overdose is reduced. Those who are part of a safe supply program are also more engaged in accessing health care and social services, which can be a stepping stone to stability and wellness.

What safe supply does is reduce reliance on toxic street drugs, which are attributable to overdose deaths in B.C. and Canada.

There’s also evidence that addiction treatment that is abstinence-based can actually create a higher risk of drug poisoning than no treatment at all. And what’s more, studies show that forced treatment for people who use drugs can also lead to increased risk of death. Not to mention it takes away bodily autonomy and dignity from folks who often feel vulnerable already.

Some have even said involuntary treatment is aligned with criminalization, intersecting with oppressive systems of colonialism, capitalism, racism, ableism and more. And the reality is that those who turn to substance use to cope with difficult situations — be it mental health challenges, houselessness or other circumstances — likely won’t stop using drugs from forced treatment. In fact, it may harm them even more.

On the other hand, overdose prevention sites and safe supply can at least tackle the largest problem right now — the massive number of toxic drug deaths that have impacted communities across the province for more than a decade.

Those who are looking to stop using drugs may also need support tackling the root of their substance use, as well as support finding stability again in the form of safe and secure housing, health care, mental health support and more.

As for decriminalization, people are less likely to seek support if they fear being arrested in relation to drug use and possession. The three-year pilot in B.C. to decriminalize personal possession of small amounts of some hard drugs runs until 2026, and I expect to see some more information on its impacts over time. For now, it has reduced barriers for people who are wanting support to seek it out.

There is also evidence that imprisonment is not only expensive for taxpayers, but does not work when it comes to rehabilitation or reducing crime. In fact, lack of support in prison as well as when an individual is released from prison can contribute to an ongoing cycle of crime.

Where do we go from here?

There’s one thing that people have right — the levels of homelessness and toxic drug deaths that we’re seeing, as well as the lack of adequate supports for people who want and need them, isn’t OK. And it really is up to the provincial and federal governments to do something about it. And it’s on all of us to demand action and results.

Measures that have already been put in place — such as safe supply, overdose prevention sites, funding and building transitional housing sites and decriminalization — are already showing promising results.

There’s hopeful news, even in our own backyard. The Village transitional housing site and recovery model, supportive housing and overdose prevention sites have been proven to not only save lives but help people achieve some stability to move forward with their lives.

These responses are recent, in the grand scheme of things, and we have decades of inaction to catch up on. Many are also in pilot phases, with governments waiting to see how these policies and projects work before improving on and expanding them.

In all the research I’ve done, and the number of experts I’ve spoken with and learned from, I’ve come to recognize there’s no single solution to these dual crises that are not only dividing our community, but putting people who are most vulnerable at risk.

Our neighbours, friends, family members and colleagues who are experiencing homelessness or who use drugs shouldn’t be vilified or shamed. In fact, Canadian physician and addiction expert Gabor Maté says shame can make drug use worse as people respond by hiding it, leading to increased risk of overdose or death.

People are complex and have different needs so, naturally, different solutions are needed to support community members in the best ways possible. Maybe, if the community continues to come together to tackle this issue from many different angles and gets the support and funding from the province and federal government to do so, we may see some improvement. But it definitely won’t happen overnight.