Kelly Black is researcher, writer, historian, and collector of books and has taught B.C. and Canadian history at Vancouver Island University. Black is the Executive Director of Point Ellice House Museum and Gardens in Victoria, B.C. This story is in response to reader questions to The Discourse, inquiring about who or what places were named for. What questions do you have about the Cowichan Valley? Send us an email and we’ll do our best to tackle them.

Since the 1800s, versions of the name “Cowichan” have been used by settlers to refer to geographic places — like bodies of water, mountains and land — as well as people and districts. Though the name has First Nations roots, it was the colonizers who decided where and how to apply it. As a result, the precise geography of “Cowichan” is complicated, and often confusing.

The origin of the name “Cowichan” is what historian T.W. Paterson called an “Anglicized corruption” of the Hul’qumi’num word “Quw’utsun” — a word that describes the peoples who live under Shquw’utsun (Mount Tzouhalem). In contrast to this highly specific place and meaning, non-First Nations people have used the word to refer to a number of different places in what is now called the Cowichan Valley, raising the question: Where is “Cowichan”? But posing this question is likely to generate different responses, depending on who you ask.

For imperial and colonial powers, giving a name to a place was an attempt to claim territory. Take, for example, the “Strait of Georgia,” a body of water named for King George III by Captain Vancouver in 1792. Of course, Vancouver’s efforts at mapping and naming began with a blank page from the deck of a ship, ignorant of the First Nations names present on the landscape for millennia. .

In an article for The Discourse, Jared Qwustenuxun Williams explains to readers the origins of the Hul’q’umi’num and hwunitum (non-First Nation) names for Swuq’us (Mt. Prevost). In that article, he notes that eventually, the hwunitum tried to claim the landscape through place naming, “… but for a time they called Swuq’us simply ‘Cowichan Mountain’.” As non-First Nations settlement increased in the late nineteenth century, “Cowichan” referred to a peoples, a mountain, a surveyed land district, a bay, a lake, a valley, an electoral district, a particular hamlet (known today as Cowichan Station) and to the general area south of the Cowichan River.

Where was ‘Cowichan’?

When non-First Nations people likely first heard the word “Cowichan,” it wasn’t even on Vancouver Island.

On his journey down the river that now bears his name, the North West Company’s Simon Fraser wrote in his 1808 journal that one of his First Nation guides feared an encounter with the “Ka-way-chin” at the mouth of the river.

Nearly two decades later, in 1825, Hudson’s Bay Company workers seeking Fraser’s route recorded that First Nations called the river “Cowitchen.” What these fur traders actually encountered were village sites. The Cowichan Tribes website explains that the Nation “…had a large summer village on Lulu Island at the mouth of the Fraser River, the site of what is now Vancouver International Airport and another large village – Tl’uqtinus (‘broad chest’) at what is now Steveston.”

Efforts to phonetically transcribe the name “Quw’utsun” into English during the nineteenth century yielded a number of different spellings. Examples from correspondence between the Hudson’s Bay Company and Colonial Office in London include “Coweigan,” “Cowitchin,” “Cowetchin,” “Cowegin” and “Cowetchen.”

Cowichan: ‘Vaguely Defined‘

Given the widespread usage of “Cowichan” to describe a people and places, it is perhaps not surprising that there arose confusion and controversy over where exactly “Cowichan” could be found.

In the local history book Water over the Wheel author W.H. Olson wrote that Victoria’s newspapers regularly described events in Chemainus as Cowichan news – apparently an affront to residents of the Chemainus District. Olson clarified: “Newcomers had no objection to the idea that Chemainus was a mere appendage to the vaguely-defined Cowichan District. To many of them, the name Cowichan had a connotation of refinement not provided by Chemainus, a place known to be populated mainly by mill-hands.”

This “refinement” likely referred to the many majors, captains, and colonels who made the Cowichan Valley their home after retirement from service to the British Empire. One such retiree was Major Claude Moss who moved with his wife Margaret to the community of Cowichan Station in 1909.

Through the spring and summer of 1914, Moss and the residents of Cowichan Station found themselves embroiled in a controversy over mail delivery and place names. Mail destined for the “Cowichan District” in North Cowichan was instead being delivered to the small hamlet of “Cowichan Station.” At a meeting in May of that year, North Cowichan’s municipal council expressed their frustration through a motion that read, in part, “…much annoyance is caused to the officials of North Cowichan municipality and to the residents within the bounds of the said municipality by reason of the fact that correspondence from outside points addressed to Cowichan district [North Cowichan] is put off at Cowichan Station owing to the similarity of name.”

The motion went on to explain that the two similar names were so confusing that people regularly made the mistake of getting off at the wrong railway station. In response to the council’s motion, an Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway official responded with support for renaming Cowichan Station.

“As far as the railway company is concerned … we have already found all sorts of trouble in connection with the same and Cowichan Lake station and vice versa. But to avoid this we have named the station at the end of our branch ‘Lake Cowichan,’” the response says.

The question of where Cowichan was clearly generated confusion – at least among travellers and postal clerks.

In early July, Moss chaired a South Cowichan meeting where attendees unanimously rejected a name change for their community, declaring the matter to be a problem for the post office. Later that month, North Cowichan council presented a collection of letters that had been delayed due to the confusion. The letters were forwarded on to the post office inspector in Victoria for consideration. Neither community was keen on a name change, and it seems that this brief controversy quickly faded when the First World War began one month later in August.

Where is ‘Cowichan’?

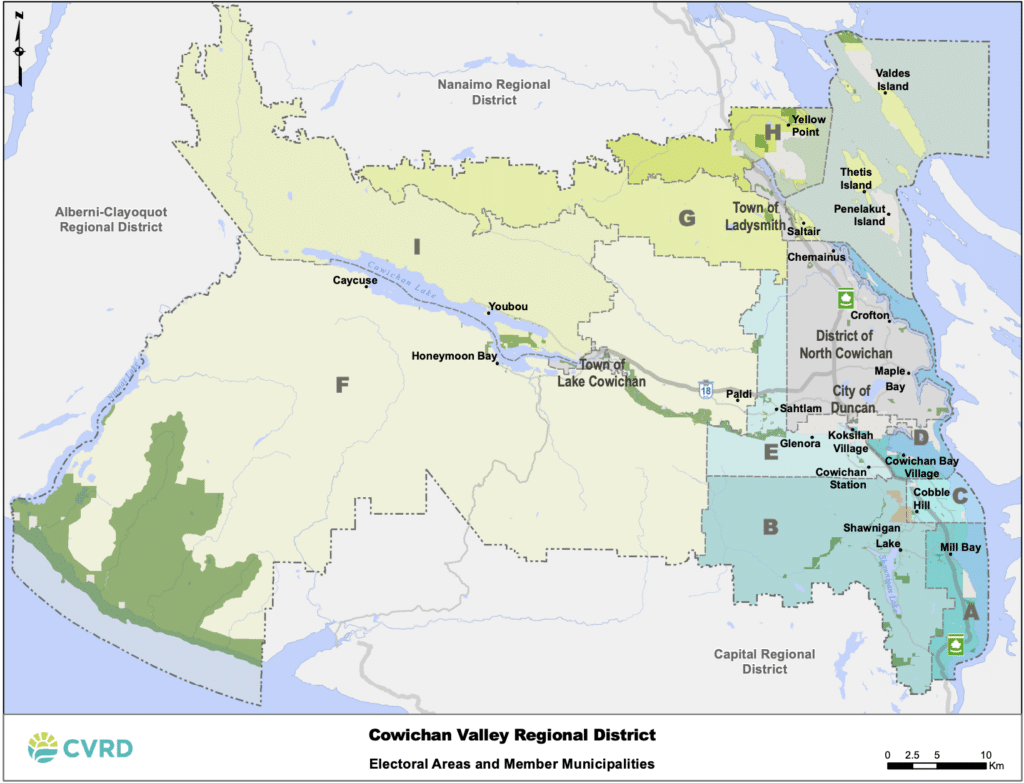

Today, the Cowichan Valley Regional District boundaries take “Cowichan” all the way to the west coast of Vancouver Island. Naming functioned as a tool of colonization and historically the name “Cowichan” was applied in numerous ways – a reminder that the language and people that turned Quw’utsun into “Cowichan” (or “Cowegian”) were not of this place. Although the English spelling may now be standardized, there has not always been agreement about “Cowichan’s” geographic meaning.

Resource list and further reading

- Digitized issues of the Cowichan Leader from VIU

- Two Houses Half-Buried in Sand: Oral Traditions of the Hul’qumi’num’ Coast Salish of Kuper Island and Vancouver Island, by Beryl Mildred Cryer (edited by Christ Arnett)

- Trading beyond the mountains: The British fur trade on the Pacific, 1793-1843, by Richard Mackie

- A Place Called Cowichan: Historically Significant Place Names of the Cowichan Valley, by T.W. Paterson

- Water over the Wheel, by W.H Olson

- Imperial Vancouver Island: Who was Who, 1850-1950, by JF Bosher

- The Warm Land, by Elizabeth Blanche Norcross.

- Simon Fraser’s Diaries (1889 edition)