UPDATED: The survey deadline has been extended from Dec. 31, 2022 to Jan. 31, 2023.

The Municipality of North Cowichan has launched a consultation that will help shape the future of an extraordinary public forest. This week, the municipality published a discussion guide and online survey, which allows the public to give feedback on four management scenarios, ranging from status-quo harvesting to no logging at all.

It’s one of the final steps in a process that began in late 2018. That’s when community members launched a grassroots effort to push the municipality to pause logging and engage in broad consultations with First Nations, experts and the public to determine how the forests should be managed.

“When I started, I was told over and over: ‘Don’t kid yourself. There’s no way. It’s impossible to stop the logging of these mountains,’” says Icel Dobell, with the advocacy group Where Do We Stand. “And we did it.”

The group succeeded in pushing for a pause in logging during the consultation period. And now, that process has resulted in expert advice, informed by the community’s desires, that show that an alternative vision for the forests is possible.

“No other community on the continent has such possibility and such power,” Dobell says. “It’s time for us to be visionaries again.”

A special forest

North Cowichan owns about 5,000 hectares of forest land, including much of Mount Prevost, Mount Tzouhalem, Mount Sicker, Maple Mountain, Mount Richards and Stoney Hill.

It’s rare for a municipality to own the forests within its borders. These lands were originally privatized as part of the E&N land grants of the 1880s, called a “a clear act of colonial theft” by the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group. Forestry companies later bought the land and logged it. North Cowichan appropriated the lands over the 1930s and 1940s, after the logging companies defaulted on their property tax bills.

Since the 1980s, North Cowichan has regularly logged parts of the forest and sold the timber to support municipal programs and services.

Related: North Cowichan review is a rare opportunity for Vancouver Island forests

These forests are on the unceded homelands of the Quw’utsun Nation, and continue to be of great material, cultural and spiritual importance. In 2021 North Cowichan and the Quw’utsun Nation agreed to form a working group to discuss the stewardship of the municipal forest lands. The land is also home to some of the rarest and most endangered ecosystems and species in British Columbia.

The four scenarios

This round of consultation asks the public to consider and rank for possible scenarios for forest management. North Cowichan hired a group of forestry experts from the University of British Columbia to develop and analyze them. The consultants built the scenarios in response to community feedback from last year’s consultations, which focused on public values related to the forest.

The scenarios are:

- Status Quo — Continue timber harvesting as it has been done in the past

- Reduced Harvesting — Cut the timber harvest to 40 per cent of historic levels, with a focus on minimizing negative environmental and social impacts

- Active Conservation — Timber harvesting is limited to areas where cutting trees can help to protect or enhance rare ecosystems

- Passive Conservation — No timber is harvested, with exceptions for cutting trees that pose a fire risk or safety hazard

There is a more detailed comparison between the scenarios towards the end of this article. Information on the scenarios is also available in North Cowichan’s discussion guide and in this presentation by the UBC consultants to North Cowichan council.

Where Do We Stand supports the Active Conservation scenario, says Dobell. Unlike passive conservation, which is essentially a do-nothing approach, this scenario opens up “exciting possibilities” for restoration and enhancement of forest ecosystems, she says. It makes way for opportunities to access funding sources that already exist to do visionary work.

And, in light of the agreement between North Cowichan and the Quw’utsun Nation to collaborate on forest stewardship, “this is an opportunity for two divided communities to come together, to envision together,” Dobell says.

The UBC consultants’ analysis suggests that moving away from status-quo logging could bring a range of benefits, including improved water quality, better habitat for plants and animals, reduced fire risk, improved viewscapes and increased wilderness recreation opportunities.

The primary cost of making this transition is a loss in timber revenue. However, the consultants’ analysis projects that the municipality could bring in even more revenue over a 30-year period by not logging, and instead turning the forest into a carbon offset project.

What’s the deal with carbon credits?

If the trees are left to grow they will capture and store tonnes of carbon that would otherwise stay in the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. Carbon offset programs allow for this carbon benefit to be quantified and then sold as credits to governments, businesses and other groups or individuals who wish to offset their carbon emissions.

For North Cowichan to do this, they’ll have to get the project verified, which means proving that the forests are storing more carbon than they would if regular logging continued. For every tonne of carbon stored, they can sell one carbon credit. The money earned is just like any other revenue to the municipality.

The process to get the project going is a bit complicated and involves some start-up costs — estimated for North Cowichan at $175,000.

But carbon credit projects are catching on as a viable way to fund conservation, particularly in B.C., where government initiatives have helped to facilitate them and, in some cases, buy the resulting credits.

For example, the Cheakamus Community Forest near Whistler developed a carbon credit project that allows it to put an end to old-growth logging in the forest and lower harvesting volumes. According to reporting by The Narwhal, the project brings in $100,000 in average annual revenue.

Closer to home, Mosaic Forest Management is also betting big on carbon credits. Earlier this year the company announced its BigCoast Forest Climate Initiative. The plan is to defer logging on 40,000 hectares of forest for 25 years, resulting in 10 million tonnes of additional stored carbon.

“We expect to make at least as much from the BigCoast Initiative as we would earn from harvesting these forests,” Mosaic’s chief forester Domenico Iannidinardo told the Globe and Mail. He estimated that the project will bring in between $100 million and $300 million in revenue.

North Cowichan’s potential carbon credit project would be relatively low risk and high value, the UBC consultants say. They describe it as a “charismatic” project, because it offers additional social and environmental benefits and would be likely to attract smaller buyers willing to pay a premium price.

While the future is uncertain, many analysts predict that carbon prices will rise significantly over coming decades, as governments seek to intensify action on climate change. The UBC consultants assumed that carbon credit prices will rise 5 per cent each year, for the purpose of their analysis.

Why older trees matter

The three scenarios that represent alternatives to the status quo have something in common: They allow the forests to get older. This happens faster in the two conservation scenarios, but it also occurs in the reduced harvest scenario.

The aging forests are related to several of the increased social and environmental benefits that these scenarios promise.

“In our area, the main thing that will enhance that native biodiversity will simply be more and extensive mosaics of old forest habitat,” said Peter Arcese, one of the UBC consultants, in a presentation to North Cowichan council.

Before industrial logging, older forests dominated these landscapes. Today, they are rare and the species that rely on those habitats have become rare, too. Restoring networks of older forest therefore creates habitat for endangered species and ecosystems.

Older forests also improve the quality and quantity of water in their watersheds. “Trees can slow the flow of water quite dramatically through landscape, and you get much less runoff,” said Brad Seely, another consultant on the UBC team, in the same presentation. Trees also improve water quality by improving filtration. It takes about 30 years after clear-cutting to recover these water services.

A recent study out of Oregon found that summer streamflow off of industrial forest lands was halved compared with that from 100-year-old forests.

Older trees also lessen the risk of forest fires. According to North Cowichan’s Community Wildfire Protection Plan, young tree plantations carry a high wildfire risk, while forests that are at least 80 years old carry a low risk. The UBC researchers found that moving to one of the conservation scenarios would decrease the high-risk area of forest by almost half.

Comparing the scenarios

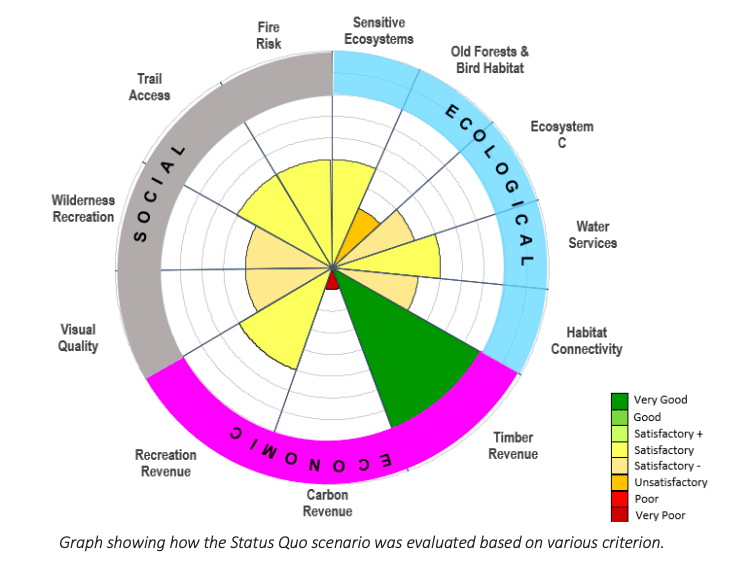

The first scenario is called Status-Quo. It assumes that the trees would be harvested and sold much as they have been over the last 30 years. This scenario offers the most short-term revenue. However, the cumulative revenue over 30 years is expected to be lower than the scenarios with very limited timber harvesting, given the assumptions the consultants made on future prices for timber and carbon credits.

The consultants gave this scenario an “unsatisfactory” score for preserving the endangered mature-forest habitat that birds and other local species depend on. The scenario also scored on the low end of “satisfactory” for habitat connectivity, carbon storage, wilderness recreation opportunities and visual quality.

The consultants note that North Cowichan would be unable to meet the minimum provincial standards for visual quality if status-quo logging continues. That’s because past logging has focused on areas of the municipal forest that are more hidden from public view. Continuing to log at the same pace will result in more intensive logging on hillsides that are visible from populated areas.

Over 30 years, status-quo logging is expected to generate $31.3 million in revenue, assuming two per cent annual growth in timber prices.

The second scenario, called Reduced Harvesting, assumes that the amount of logging would drop to about 40 per cent of the status-quo level. Doing so boosts the scenario’s scores for protecting sensitive ecosystems, water systems, wilderness recreation opportunities and visual quality.

However, timber revenues would fall to less than 40 per cent of the status-quo, as the costs of harvesting would rise because of more selective logging practices. But in this scenario, North Cowichan could still implement a carbon offset program and sell credits associated with the reduced intensity of logging. This scenario could generate $30.7 million in combined timber and carbon credit revenue over 30 years, the report suggests.

The next scenario, called Active Conservation, allows for timber harvesting only in specific areas where doing so is expected to enhance biodiversity and protect endangered ecosystems.

The consultants identified parts of the forest that have very dense stands of Douglas fir trees, 40 to 60 years old. These areas could be thinned out by removing some of the trees, which speeds up the process for these stands to develop the characteristics of a mature forest. This helps the mature forest habitat — which has become endangered because of intensive logging in this part of the world — and helps species that rely on this habitat as well.

They also identified areas where conifer trees are encroaching on places that used to be woodlands, for example the open meadows associated with arbutus and Garry oak trees. By removing the conifers, these rare ecosystems could be enhanced and preserved.

Because of its focus on ecosystem preservation and enhancement, this scenario scores highly on environmental and social outcomes. (As a note, the consultants were unable to quantifiably differentiate between the four scenarios on trail access and recreation revenue, and therefore gave them an equal “satisfactory” score on these measures.)

The revenue from this scenario is from its potential as a carbon credit project. While some revenue could be generated from the limited timber harvesting, the consultants project that the cost of these activities would be slightly more than the revenue generated from them. With all revenue and costs considered, they suggest that this scenario could bring in $35.1 million over 30 years.

The Passive Conservation scenario limits all timber harvesting, with exceptions for removing trees that pose a fire risk or safety hazard.

It is very similar to the Active Conservation scenario, but without the forest management activities related to thinning dense conifer stands and removing conifers from woodland areas to enhance and preserve rare ecosystems.

This scenario scores similarly high on environmental and social outcomes. It also holds the highest possibility for revenue as a carbon project. The consultants estimate that it could generate $39.6 million in carbon credit revenue over 30 years.

What’s next?

The online survey for this round of engagement closes on Jan. 31, 2023. North Cowichan has also hired consultants to conduct a phone survey, in order to get a representative sample of residents.

Residents are also invited to register for one of two online information sessions, Tuesday, Dec. 6 from 6 to 8 p.m., and Monday, Dec. 12 from 6 to 8 p.m.

More information is available on North Cowichan’s public engagement website, where residents can also ask questions directly to staff.

Following the engagement period, the UBC consultants will present a report to council summarizing the public feedback.

From there, North Cowichan council will be tasked with the hard work of integrating the community’s wishes — and any potential recommendations from its working group with Quw’utsun Nation — into a plan for the future of the forests.