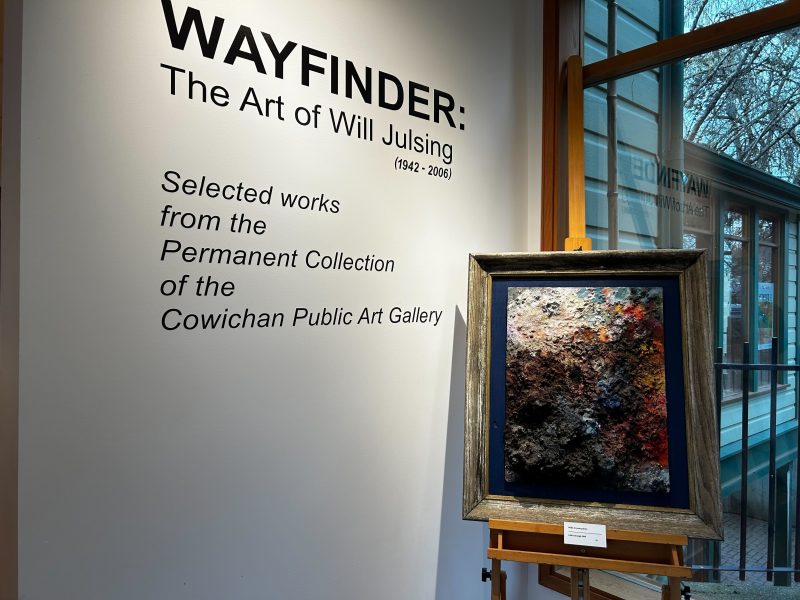

For the past couple of weeks, a room in the Cowichan Valley Arts Council studio gallery has become a space hosting some of people’s personal experiences.

What appears to be a clothesline hangs along the walls of the room and on the clothesline are images and text from community members. Some of the images are of store shelves stocked full of menstruation products or pad and tampon dispensers in bathrooms, while others are of underwear and pads stained with blood.

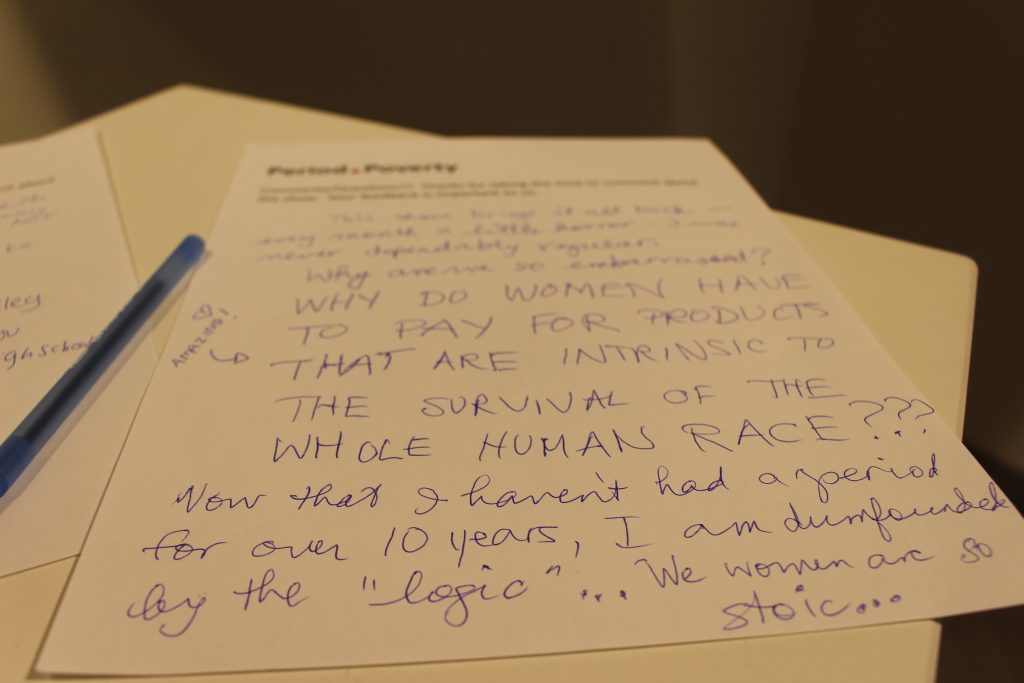

Visitors to the gallery have mixed experiences as they enter the space. One person takes time to write their own comments on the exhibit on sheets of paper around the room. Another person walks in with their partner, asking if they ever considered how expensive period products are or the stigma associated with periods.

The exhibit, called Period Poverty Cowichan, explores the many experiences of people who menstruate through photos and text that they’ve taken and written. It’s part of a larger project, led by the Cowichan Women’s Health Collective, to address period poverty, stigma associated with menstruation and how period products can be more accessible and available in the community. Period poverty refers to a lack of access to menstrual products and can be related to financial barriers, as well as societal barriers.

The exhibit is on this week, daily from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. through Friday, Nov. 10.

Throughout the course of the project, the Cowichan Women’s Health Collective has conducted research through focus groups and a survey. It has also partnered with local organizations to distribute period products throughout the Cowichan Valley and collect their feedback. What they’ve learned is that period poverty touches everyone — in one way or another — and that more needs to be done to reduce stigma and make necessary products accessible to those that need them.

“Speaking to new parents, parents with a number of children, teenagers — there was no group that did not have stories for us,” says Rhoda Taylor, a researcher with the Cowichan Women’s Health Collective period poverty project.

Project will contribute to provincial period poverty task force

In May 2022, the province announced it would provide $750,000 in funding to United Way British Columbia to support a task force that explores ways to end period poverty in B.C. The provincial funding supports United Way’s Period Promise campaign to distribute free menstrual products across the province and research what period poverty looks like in B.C.

Almost one-third of the funding was also allocated to 10 pilot projects across the province that are working to end period poverty — including the project led by Cowichan Women’s Health Collective. Learnings from the pilot projects will contribute to recommendations made by the Period Poverty Task Force to respond to period poverty in the province.

In the Cowichan Valley, the Cowichan Women’s Health Collective sought to better understand stigma associated with menstruation and barriers to accessing period products. The organization hosted focus groups with people of varying ages and backgrounds, conducted an online survey and supported people to share their experiences through the photovoice exhibition at the Cowichan Valley Arts Council Gallery.

Taylor says they heard from people as young as 12 years old all the way up to parents who have teenagers themselves. Respondents experienced varying levels of poverty and living situations, all of which impacted their access to period products.

“At the focus groups, we asked if there are people who would like to participate in the photovoice display by taking photos … and it was interesting that a number of people were very happy to do so. They especially said that they communicated best visually, and not verbally or by text,” Taylor says. “And certainly when people got comfortable talking, there was a lot that was said about the experience of the cost of menstrual poverty.”

Over the course of six months, the Cowichan Women’s Health Collective distributed over 19,000 individual menstrual products. Most of them were single-use, such as pads and tampons, but they provided some reusable products as well, according to Cowichan Women’s Health Collective executive director Beverly Suderman. The collective worked with 17 different local organizations to distribute products and interviewed service providers at the organizations about their experiences doing so.

All of the data collected from the focus groups, surveys and interviews was compiled into a report and provided to the province, Sudermand says. The final report will be available to the public soon, once the province gives the collective permission to release it.

Period products becoming increasingly expensive

According to research conducted by United Way B.C., half of everyone who menstruates in the province — including women, girls, people who are non-binary and people who are trans — have struggled to buy period products at some point, and more than a quarter have had to experience a period without any menstrual products. Period poverty can also impact caregivers of people who menstruate, who may have to purchase products for their dependents.

A person could experience around 13.6 menstrual cycles per year with each lasting around five days. This means they might bleed for an average of 68 days out of the year. Each day they bleed, they require menstrual products, the United Way says, but some people could bleed for longer or shorter periods of time or experience more or less cycles than the average.

In their lifetime, a person who menstruates could spend thousands of dollars on period products and related products like painkillers or heating pads, Suderman says. And the United Way says that number is increasing with inflation. In the past year, the cost of personal care items, including pads and tampons, has increased by almost six per cent, according to Statistics Canada. And the United Way says those living in rural communities may see even higher prices and limited access to period products.

“All said, menstruation is a deeply personal experience that arrives unannounced and, for those who experience period poverty, can become an unwelcome and uncontrollable barrier to community,” the United Way report says.

People end up missing social events and outings, school and work due to periods — especially when they don’t have access to period products — the United Way says, and both Suderman and Taylor say this was reflected locally in Cowichan, too.

Taylor says some focus group participants and survey respondents were mothers with multiple teenage daughters. They said the cost to supply their kids with pads, tampons and painkillers every month is incredibly high.

“One of the things that some of our youth-serving agencies talked about was how the youth themselves didn’t help themselves to [period] products, but their parents did when they came to pick them up,” Suderman says. “The more menstruating people there are in a home, the more expensive it gets to be.”

Reusable products can be a significant investment, Suderman says. It can be risky purchasing products like a menstrual cup or reusable pads because they may not be the right fit for someone, and also can’t be returned. Reusable products also require the user to have a safe, clean space to wash the items, which might not be accessible to everyone.

“There’s a direct linkage between poverty generally and period poverty,” Suderman says.

Those who couldn’t afford menstrual products were often stuck at home, Suderman and Taylor say, and they lost more money because they couldn’t go to work.

Taylor says some of the service providers the Cowichan Women’s Health Collective has partnered with to distribute menstrual products may not be able to continue once the funding runs out, due to the high cost of products.

At the photovoice exhibit, several images speak to the cost of products. One photo features a package of pads on the left and an empty plate, with the words “you decide” in it, on the right. An experience in the exhibit spoke to the cost of replacing stained items such as clothing, bed sheets or a mattress. Another image shows store shelves in the background, lined with period products, and a hand holding up a five dollar bill in the foreground.

“Having to choose between a month’s supply of menstrual supplies and my first meal in three days is a hard choice,” the text on the image says.

Comments written on paper by visitors to the exhibit question the cost of menstrual products as well.

“Why do women have to pay for products that are intrinsic to the survival of the whole human race?” one comment reads. “Amazing!” says another comment next to the first one, with a heart and an arrow pointing to it.

A desire to talk about it

One image in the exhibit is a photograph of a tree with menstrual products hanging off it.

“What would the world be like if feminine products were this accessible? What if they really did grow on trees?” the text accompanying the image says.

Survey and focus group participants addressed the stigma attached to periods and inaccessibility of products, Suderman and Taylor say. Youth, in particular, were vocal about lack of education around periods in schools and the topic being considered taboo.

“The youth just really pushed hard about it,” Taylor says. “They’ve said how little some of the boys knew. There was some discussion about the difficulty that trans individuals were facing. They were really upfront about the stigma, and it is a topic that is clearly not talked about and not permitted to talk about.”

An image in the photovoice exhibit shows a hand holding cell phone with 9-1-1 on it. The text accompanying the image details one person’s experience being surprised by their period.

“I was in my van parked in the middle of town, farmer’s market going on, people everywhere. I was scared to get out of the van because I had no products and my period had started. My friend wanted to work on the van and I wouldn’t get out of the van ‘because I am bleeding to death!’ So he called 911. Of course the ambulance wanted me out of the van to talk to me so I told them ‘no.’ They left after talking with me. I didn’t want to get out.”

Suderman says that as they parsed out the story and thought about it, they recognized that this individual had internalized enough shame about their period that they could speak about the bleeding, but couldn’t acknowledge what kind of bleeding it was.

When advertising the period poverty survey on Facebook, Taylor and Suderman say it was also met with stigmatizing responses. For example, one response questioned why the government was getting involved in the private business of citizens.

But Suderman says that issues around period poverty impact both individuals and the community.

“If [people who menstruate] are experiencing period poverty, in whatever form that takes for them, they’re missing school and missing work. And that also has economic ramifications,” Suderman says.

Lack of knowledge around periods and menstrual health can also impact a person’s understanding of whether or not what they’re going through is normal. An example that came up in the focus groups is of a person who has a clotting disorder. Their health condition meant they were experiencing long periods with very heavy bleeding, but they thought what they were experiencing was normal. It wasn’t until they required medical intervention that they learned it was an issue.

While education can be an antidote to stigma, Taylor and Suderman say the education that people receive in schools is also inconsistent, according to what they’re hearing. Some students receive a robust education about menstruation, with teachers going above and beyond curriculum and students of all genders participating in the conversation. But in some cases, students are taught the bare minimum from teachers who may not be comfortable or knowledgeable about the subject.

Schools are mandated by the province to supply menstrual products for students, but the way in which the products are distributed isn’t always accessible, Suderman says. Due to a fear of stealing and wasting products, some schools keep things like pads and tampons in a counsellor’s or administrator’s office. This means that a student who is surprised by their period in the bathroom may have to put their clothes back on and walk down the hall to ask for supplies.

“And then they have to go back and they feel like everybody knows what’s going on, which if we were in a culture that celebrated menstruation that would be like ‘hey, you’re on your period, how fantastic.’ But we’re not in that kind of a culture. We’re still in the kind of culture where it’s meant to be a secret and often viewed as dirty and shameful,” Suderman says.

Other key learnings about period poverty in Cowichan

The research that Cowichan Women’s Health Collective has undertaken about period poverty has surfaced other learnings as well.

Taylor says they learned that some of the most vulnerable people in the community who are dealing with extreme poverty or addiction may not menstruate at all because stress, weight and malnutrition can impact whether or not people have periods. Many were also on a form of birth control that suppressed their periods.

They also learned that women who have just given birth may turn to menstrual products when dealing with incontinence. This is a symptom of women’s health needs not being met by the health system, Suderman says. Medical services like pelvic floor therapy could help with incontinence issues, but it’s not often accessible or talked about, leading people to seek out menstrual products to deal with incontinence issues instead.

Many unhoused people also don’t have access to laundry facilities, Taylor says, which can become a major issue for people who are menstruating.

“If your period starts and your clothes get stained, how do you cope with that?” Taylor says. “Women who do have washing machines have enough trouble and end up throwing their clothes away … How do you deal when you’ve only got a change of clothes and nothing else? And you have to throw your clothes out because there’s no way to clean them?”

Headed in the right direction

While Suderman and Taylor say they had some assumptions about the impacts of period poverty in the Cowichan Valley, they say they learned a lot from conducting the research, too. They credit that to creating space to talk about something that isn’t normally discussed.

“We got into things we didn’t know going in and the conversations became very broad,” Taylor says. “When people understood why we were asking the questions, they fully engaged and the discussions were both fascinating and very deep. It was made clear that it was a discussion that wasn’t being held that needed to be held.”

But things are improving, and the fact that this funding was made available to conduct this research is a sign of that, Taylor says. People are asking questions and doing the research to know what questions to ask people with lived experiences.

“Kudos to whoever, along the route, has listened and has now provided funding,” Taylor says. “And now, hopefully, they’re going to listen to the research.”

For the Cowichan Women’s Health Collective, Suderman says their next goal is to establish a community health centre focused on meeting the needs of self-identified women and girls. Once that is running, Suderman says part of its service model will be to ensure menstrual products are available for the community.

“Menstrual products are basic hygiene,” Suderman says.