How can the media do a better job of covering refugee issues? What tools and tips should refugees have when speaking with journalists? In June 2018, The Discourse facilitated four evening workshops to explore these issues. We invited refugees and settlement workers to join the discussion and share their perspectives.

This toolkit is a summary of what we learned through phone calls, emails and an in-person workshop series we hosted to bring together newcomers, refugees, academics and those working in settlement services.

We’ve divided what we learned into two parts: Tips and tools for newcomers to Canada dealing with the media, which we published here, and these tips and tools for journalists covering refugee issues.

Our workshop series is just the start of this discussion so we hope to keep updating these ideas as the conversation continues to diversify and grow.

Tips for interviewing refugees

[discourseImage id=”9805″ size=”text”]

“I would love to advise journalists to listen carefully when it comes to interviewing refugees. When they’re listening to refugees they have to listen to the whole story and not be selective to one certain story,” says Ely Bahhadi (pictured above), a Masters of Journalism student at the University of British Columbia and privately sponsored Syrian refugee.

-

-

-

-

-

- Be aware that journalism has different roles in different countries. Explain clearly who you are, where you work and the type of journalism you do. Journalism can have a range of roles depending on the country. Workshop participants linked journalism with positive and negative qualities, ranging from the idea of journalism as a social service to journalism as a tool for politics and propaganda. Many refugees come from countries where media messaging is strictly controlled by the government. Being aware of these differences and explaining how journalism works at your publication can help put prospective interviewees at ease.

- Make it obvious that saying “no” to an interview is okay and ask for permission before going on the record. Make it clear how you plan to record your interactions. Will you be recording audio, video and taking photos?

- Refugees can be in precarious positions and identifying themselves can put them or their family in danger. Be clear about how you will be identifying them in the story. Will you use their name? Photo? Can their identity be put together through the various descriptions in your story?

- Be aware that interviews and conversations with those fleeing persecution can cause emotional stress, particularly if interviewees are unprepared to discuss past traumas. Let them know the topics and issues you hope to cover in your interview in advance so they can be prepared to answer your questions. In addition, you can point them to local nonprofits who offer counselling for trauma, such as the Canadian Centre for Victims of Torture in Toronto and the Vancouver Association for Survivors of Torture.

- Let them know it is okay to be critical and be aware of the different stages people can go through when adjusting to new environments. Here is a description of the phases of culture shock. Interviewing someone in the “honeymoon phase” of their arrival or “crisis phase” could influence the type of responses you get. Journalists need to understand culture shock and a refugee’s unique situation upon arrival says Mohammed Alsaleh who came to Canada in 2014 after fleeing persecution in Syria. Because when asked for an interview, he says, refugees could feel “pressure to say yes or to show only appreciation.”

- Do your research. Before interviewing someone, take the time to learn about their home country and culture. This context will allow for a more deep and meaningful interview.

-

-

-

-

Best editorial practices

“As media, we have a huge role to play. We can’t force things to happen, but we shed light on what’s happening on the ground. But then there should be a more developmental story. ‘Oh, we covered this three months ago’, and then there should be ‘What’s happening next?’” says Qaabata Boru, an Ethiopian exiled journalist currently in Canada.

-

-

-

-

- Make your editorial standards and practices public and accessible. Share your organization’s policies and practices ahead of your interview so the person you are interviewing has a better idea of how your organization’s editorial process works. Let them know who your audience is and if there is potential for their stories to be seen in their home countries. By sharing their story and identity, some refugees risk the safety of their family and friends back home.

- Share past work ahead of the interview so the person you are interviewing can get an idea of the types of stories and issues you or your organization covers.

- Go beyond describing someone you interview as a refugee from their home country. Depicting refugees as helpless victims looking for handouts can add to stereotypes and racism. What was this person’s life like before arriving in Canada? What are they aspiring to do here?

- Clarify how you’re using what they tell you. If you’ve met with a refugee multiple times and had a range of discussions about their experience, it may be worth calling them once your story is done and walking them through what information is going to be in the piece. While not a typical journalistic practice, given that language can be an issue and people are often in vulnerable circumstances, it’s important to make sure you are being accurate and not putting them at risk.

- Follow up with those you speak to and share the story with them. Let them know how they can follow your reporting.

-

-

-

Increasing diversity of refugee coverage

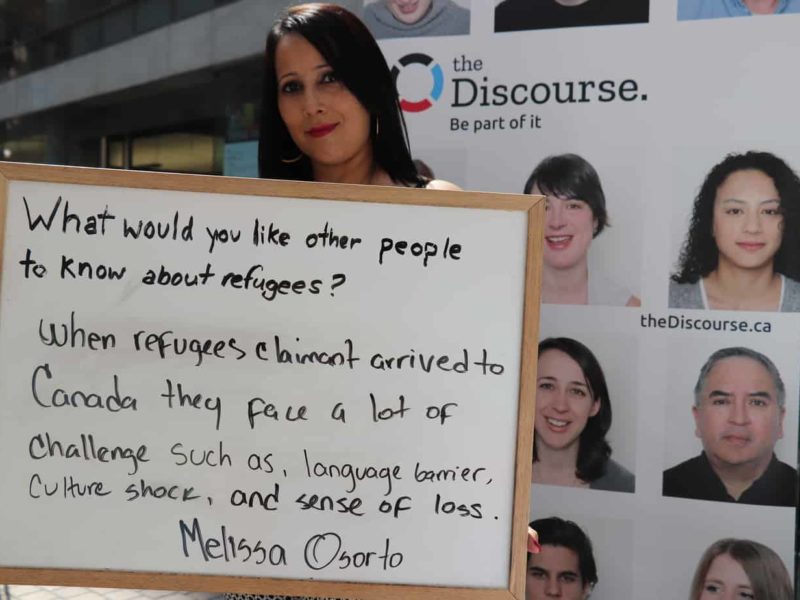

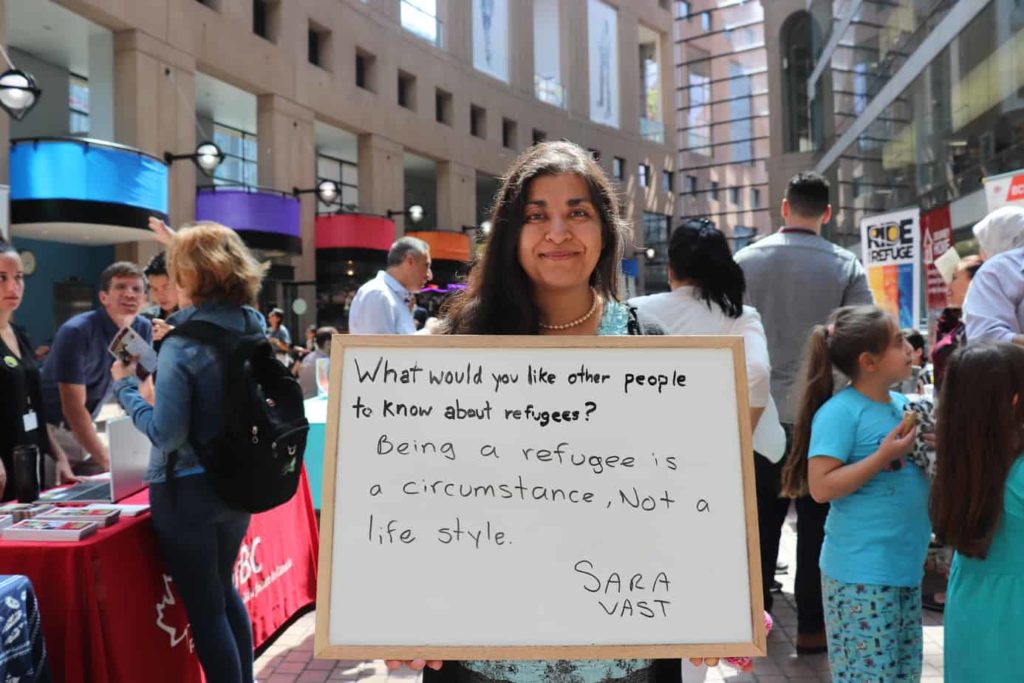

[discourseImage id=”9838″ size=”text”]

“We are hoping people will not have the wrong impression when they hear the word ‘refugee’ and they will have a much better understanding in different types of refugees,” says Rainer Oktovianus (pictured above), a workshop participant who fled to Canada from Indonesia with his husband. “Let our stories continued to be heard in hoping someday the world don’t need the word ‘refugees’ anymore,” As a photographer in Vancouver, Oktovianus is working on a project called #BreakTheStigma to fight against discrimination and stigma surrounding LGBTQ, HIV, mental health and racism.

-

-

-

- Be aware of the different stages of the settlement process. People fleeing conflict or danger come to Canada in many different ways and the process can take years. Because of that, the challenges they face when resettling in Canada are very different from person to person. Here is a glossary of terms to be aware of from the Canadian Council of Refugees that describes the types of claimants.

- Seek diversity in coverage. Refugees flee danger from all over the world for many reasons, not just armed conflict. Social unrest and persecution can cause people to fear for their safety. Here is a data portal provided by the UNHCR of refugee data around the world. Here is data provided by Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Board.

- Think of accountability from all sides. Federal, provincial and municipal governments have a role to play in resettlement, as do settlement organizations, NGOS, international organizations, lawyers, non-profits, Canadian citizens and society as a whole. The ministry of immigration and elected officials are often the focus of accountability stories about the refugee resettlement system, but workshop participants raised questions about other organizations who also play a role in resettlement. [end]

-

-

This was made possible by contributions from over 30 refugees, newcomers and settlement workers who spoke to us over the phone, in person or attended our workshop series. The workshop was supported by staff and volunteers at Pacific Immigrant Resources Society and Options Community Services.

This work was edited by Lindsay Sample, with fact-checking and copy editing by Jonathan von Ofenheim. With files from Brenna Owen and Julia-Simone Rutgers.

Special thanks to the people who attended the workshops or gave their time and input through other means.