How can the media do a better job of covering refugee issues? What tools and tips should refugees have when speaking with journalists? In June 2018, The Discourse facilitated four evening workshops to explore these issues. We invited refugees and settlement workers to join the discussion and share their perspectives.

This toolkit is a summary of what we learned through phone calls, emails and an in-person workshop series we hosted to bring together newcomers, refugees, academics and those working in settlement services.

We’ve divided what we learned into two parts: Tips and tools for journalists covering refugee issues, which we published here, and these tips and tools for newcomers to Canada dealing with the media.

1. Ask the journalist questions before agreeing to an interview.

You should ask a journalist questions about their work and approach before agreeing to speak. You could ask to read the journalist’s past work, about the stories and topics their organization covers and their standards and practices. This can help you understand what biases that journalist or their media outlet might have. You can also ask a journalist why they want to interview you, how they plan to use your story, when and how it will be published, and how they will follow up. Considering all of these factors can help you make a decision.

Here are some questions to consider:

-

- Who do they work for? (What is the name of publication? Are they a freelance reporter?)

- What is the story about?

- What is their deadline?

- What will the final story look like and how long will the story be?

- How much time will the interview take?

- How will the interview be recorded?

- Will someone take photos or video of you?

- Will they have to follow up with anyone about you or require any documents for fact-checking?

- Who else will they need to talk to in order to verify your story?

- Where will the story be published? What is the audience of the publication? (Is it local, national or international?)

2. If you agree to an interview, be prepared to have your image and words recorded.

For example, a journalist might ask:

-

- For a phone or in-person interview which will be recorded

- For you to send a photo and information about the photo such as who took it, where it was taken and when

- To take photos of you at the interview or arrange a time for a photographer to take photos of you

- To record video and audio

- For other contacts/people you know that they could interview

- To contact people who can back up parts of your story such as lawyers, employers, other family members

3. Ask to see the organization’s journalistic principles and practices. This will give you an idea of how editorial decisions are made.

Each media organization has their own process to decide what news to cover, what information to include in a story and what information to keep out of a story.

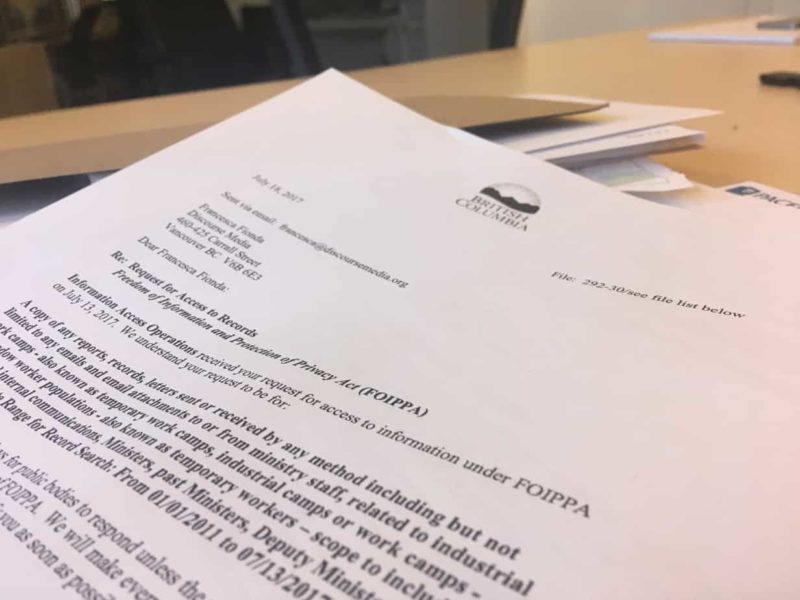

When you are approached for an interview, you can ask journalists for their company’s editorial practices. For example, here are The Discourse’s 10 principles that guide our editorial practices. Here are the CBC’s journalistic standards and practices.

You can also ask a journalist what kind of story they are working on. Different types of stories have different restrictions. For example, daily news reporters typically publish stories very quickly and have a limited word count or air time for TV or radio to capture information. Reporters who are working in current affairs, documentary or investigative journalism will have more flexibility, but will also likely follow up with you multiple times.

Speaking with a reporter doesn’t mean you will be included in the final story and not everything you tell a reporter in an interview will be included in the story. Sometimes, you might speak with a reporter for hours or over multiple days and only one thing you said is mentioned in the final published story. While your quotes or name might not appear in the final story, your experiences and perspectives play a critical role in shaping a journalist’s overall understanding of an issue.

4. Media organizations may have different political leanings. Look at their past coverage to get an idea of where they stand.

Different news organizations can have different political leanings. Read through their articles online to see what issues they cover, how they write their headlines and what voices they include in their storytelling to get a better idea.

Also be aware there is a difference between opinion pieces and news stories. Opinion pieces often express a personal argument. News stories generally do not include personal arguments and seek multiple sides of an issue. You can ask a reporter if they are writing an opinion story or a news story.

5. If you are worried about being identified, tell the reporter before you agree to the interview. Confirm what actions they will take to protect your identity.

It’s important for reporters to share the identity of the people they interview to add credibility to the information they are presenting. However, if you are worried for your safety and security, you should explain this to a reporter and they can explore ways to protect your identity.

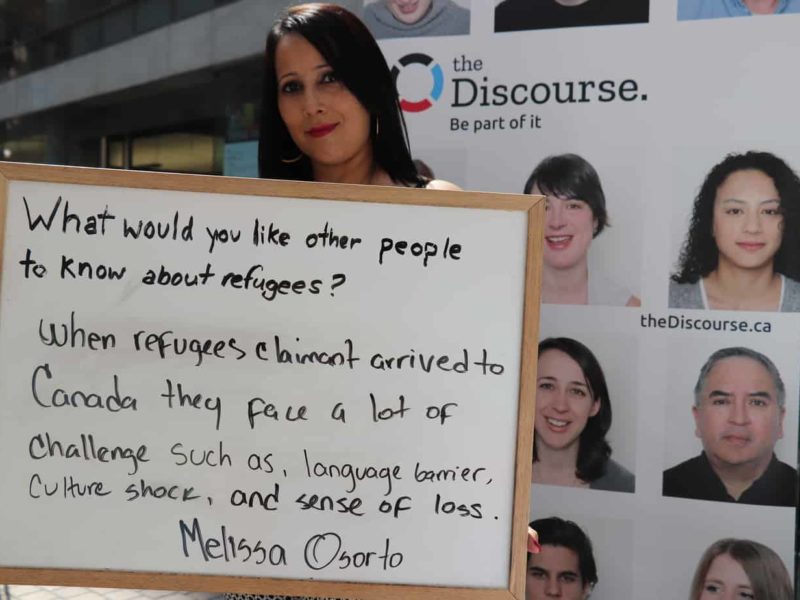

“My advice is for refugee claimants and refugees and protected persons that will appear on media is be aware who is asking your information in order to protect your family, your beloved people back in [your] countries,” says Sara Lopez who came to Canada six years ago. “This is because there is a lot sensitive information in these refugee cases. And sometimes it’s very hard to explain what the situation was.”

If you do not want to be identified, you should bring this up immediately. Here’s an example of how reporter Brielle Morgan used creative photos to protect the identity of a mother she interviewed for a story about the child welfare system:

[discourseImage id=”9584″ size=”impact_channel”]

6. Your story could be seen around the world

Some media companies focus on print, radio or television, but generally, most publications in Canada also share their content on their websites or through social media like Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The audience for newspapers in Canada is shrinking. Most people in Canada go online or turn to social media for their news. Here’s a recent digital news report from the Reuters Institute that looks at the major sources of news in Canada.

Sometimes, social media comments can be racist and hateful. While there are laws that protect freedom of speech in Canada, there are also laws that are meant to prevent hateful comments. If you want to report any comments you see, social media sites and organizations should have people monitoring comments to remove them if they are inappropriate.

-

- Here’s how to report potential abuse on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/help/www/181495968648557?ref=u2u

- Here’s how to report potential abuse on Twitter https://help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/report-abusive-behavior

- Here are The Discourse’s guidelines for commenting on social media:

https://thediscourse.ca/community-guidelines

7. Be prepared to back up parts of your story with documentation, photos or names of people you know

Accuracy is one of the most important parts of journalism. Each organization has different ways they check information in their stories. If you are interviewed, a reporter might ask for documentation to back up what you are telling them. For example, if you say you became a Canadian citizen in 2010, a reporter may ask for your citizenship certificate, photos of your citizenship ceremony or to speak with someone who helped you in that process.

This is not because they don’t trust you. It’s part of the process to make sure what journalists publish is true. You can ask what a reporter’s fact-checking process is and read their editorial practices. You are also free to end an interview or decline to share information if you feel uncomfortable.

8. Confirm if the conversation you are having is “on the record” or “on background”

There are different types of conversations you can have with a reporter. Generally speaking, “on the record” means everything you say can be published and you can be identified. Sometimes a reporter will say a conversation is “on background.” Usually, this means they will use the information you tell them but won’t quote you. “Off the record” means they will not report on what you tell them unless they can find other people to verify what you say.

If you prefer to have a conversation “on background” or “off the record,” it is important to clarify exactly what the reporter means before you have a conversation with them.

Here’s what the Canadian Association of Journalism says about these kinds of conversations.

9. If you want to share your perspectives, find reporters or organizations who have shown interest in similar topics

Look for reporters/advocacy organizations/social media influencers who cover the issues you are most interested in and contact them directly. If you can, send a short email summarizing your perspectives on the issue, why it’s important for them to cover it and why you are qualified to speak to that issue. Follow up with a phone call if you are able to find the direct number.

You should be able to find their contact information on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook or on the websites. The best way to get a reporter’s attention is through a short email and a follow up phone call.

Social media is another powerful tool to engage the public. The Canadian Council for Refugees has this list of resources for advocacy.

You can also contact advocacy groups that are already trying to raise awareness around issues you are passionate about. Here is a list of groups across Canada that focus on refugee issues.

10. Be prepared that speaking about past traumas can be stressful and triggering

Before you agree to an interview, you should consider whether you can cope with the emotional stress and how you will respond to emotions that arise from the process.

Here are some organizations that can offer help:

Background on journalism in Canada: Your questions answered

Throughout our workshops we heard a number of general questions about journalism in Canada. Here are those questions answered:

- What is the role of journalism in Canada?

The media reports on current events, explains and provides context to issues in society, uncovers hidden truths and holds government and decision makers accountable for their actions. At The Discourse, we see journalism as a way to bring together communities, surface solutions and increase diversity in storytelling.

- What is the relationship between government and media?

In Canada, the government has no direct control over what issues journalists cover. While the media does report on what the government is doing and what elected officials say and do, it also holds the government accountable for its decisions and is often critical of government programs and officials.

The federal government provides funding to the national public broadcaster, the Canadian Broadcast Corporation (CBC). This money comes from taxes paid by the public and does not impact editorial decisions.

- How is journalism regulated? Do journalists need a certificate or license?

Generally, journalists do not require any specific degrees or licenses to publish stories, though many choose to take courses or education programs that offer journalism training.

Freedom of expression gives every citizen, including journalists, the right to express their opinions. Section 2(b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.” To balance that right there are also laws that protect citizens from false information as described here by the Canadian Journalists for Free Expression.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) regulates broadcast and telecommunication services across the country. This includes cost, accessibility, ownership and broadcast licensing.

Our workshop series was just the start of this discussion so we hope to keep updating these ideas as the conversation continues to diversify and grow. [end]

This story was made possible by contributions from over 30 refugees, newcomers and settlement workers who spoke to us over the phone, in person or attended our workshop series. The workshop was supported by staff and volunteers at Pacific Immigrant Resources Society and Options Community Services .

This piece was edited by Lindsay Sample, with fact-checking and copy editing by Jonathan von Ofenheim. With files from Brenna Owen and Julia-Simone Rutgers. The Discourse’s executive editor is Rachel Nixon.

Special thanks to the following people who attended the workshops or gave their time and input through other means. We plan to keep adding to this list as we get more feedback.

[factbox]

While you’re here…

What is the one thing that is connected to low voter turnout, the spread of infectious disease, decreasing public accountability, and growing distrust of our neighbours? The decline of the news industry. In Canada, nearly 250 media outlets have closed in the past decade.

That’s why The Discourse is stubbornly dedicated to building a new kind of journalism that serves people, not advertisers. Because Canada needs journalists to provide accurate and unbiased information about polarizing issues, to reflect Canadians’ diverse perspectives, and to hold power to account.

We can only build the new media Canada needs with your help. Become a member of The Discourse to contribute to journalism that’s having an impact. Pay what you can — it only takes a minute. Thanks.

Become a member of The Discourse

[/factbox]