Lisa Mizan had never heard the word “rape” before but as soon as she woke up, she knew something was wrong.

Mizan was 17 years old and an international student just starting frosh week at Brandon University, a small campus of about 3,000 students in southwest Manitoba, about 200 kilometres west of the provincial capital of Winnipeg.

It was 2015 and everything was new: it was her first week at a new school in a new country. And the night before, she had been a virgin.

She decided to tell a Brandon employee what happened. She believed that reporting the assault to someone at school would help ensure she wouldn’t have to see the alleged perpetrator on campus any more. So she talked to someone at student services, who referred her to a counsellor.

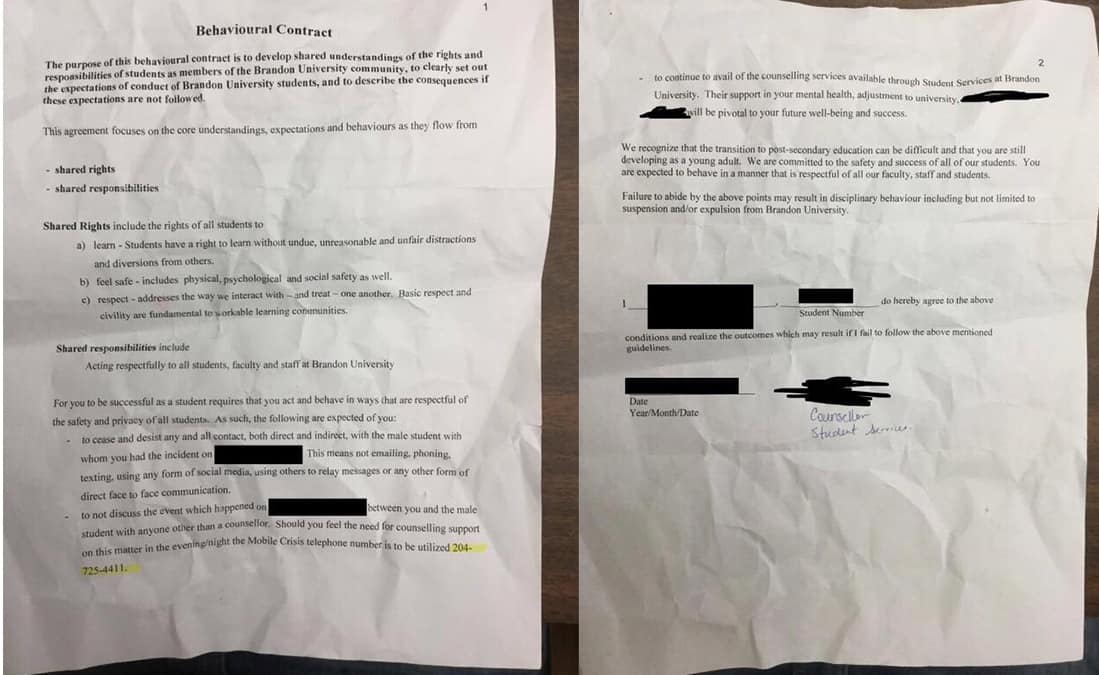

The promise of help came with a catch: she would have to sign a behavioural contract agreeing not to tell anyone other than a counsellor what had happened.

If she violated those terms, the contract said, she could be disciplined, suspended or even expelled from school.

Mizan’s story is not unique. More than 260,000 students told Statistics Canada in 2014 that they had been sexually assaulted, and studies have shown that students across North America may be particularly vulnerable in their first few weeks of school. Like Mizan, many of those students may face school policies or practices stifling their ability to tell anyone what happened.

According to one study, nine Canadian universities restrict how survivors can speak about their assaults. Some legal experts and student activists call these policies “gag orders” and say they violate free speech and undermine both students’ ability to heal and their chance to challenge the prevalence of sexual assault on campus.

Mizan felt she had no choice but to sign the contract. She didn’t want to keep seeing the student she says assaulted her on campus. She wanted to feel better.

“There was a lot of authority around me. That’s why I signed it,” she told The Discourse. “And the counsellor was also like, ‘If you break this, you’ll get expelled.’ And I was just like, ‘Why will I get expelled? I didn’t do anything. Will I be able to tell my story to people?’”

In the months that followed her silencing, Mizan says everything got worse. She says she was moved from her residence room but couldn’t tell her friends why. She started drinking more to calm her thoughts. She began self-harming. The residence supervisors were concerned, she says, but would do little except call the police whenever she said she felt unsafe.

“I kept saying, ‘This is not my fault. You made me this way.’”

Mizan says being silenced was even more traumatic for her than the assault itself. “It wasn’t what happened. That happened, and I think I would have gotten better,” she says. “It’s just the way that I was handled, just the way that I was silenced.”

After suffering alone and in silence for more than a year, she finally decided to speak out, despite the threat of expulsion.

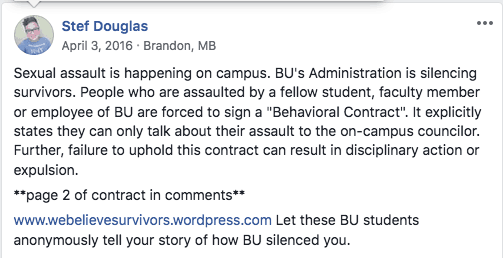

She met other survivors and told them about what had happened. Then she shared the behavioural contract with Stefon Irvine, a student leader on campus, who was shocked. He soon posted it on social media in protest.

One day later, Brandon’s administration responded — and rescinded the policy.

‘Wow, we both know this is so wrong’

When Stefon Irvine heard about the gag order, he knew he had to do something to help Mizan and other survivors.

“I was just shocked,” says the Métis student who was studying nursing and leading the school’s LGBTTQ* collective at the time.

“It just really threw me off that the institution I’ve been at since 2010 would do something like this,” he says. “Students are the heart of this institution, and if the institution doesn’t care about the students, then what am I doing here?”

“Once the shock started to wear off, it was like, I need to move on this,” he continues.

Irvine says he’d heard rumours that a student was assaulted but blocked by the university from talking about it. “Brandon being such a small institution, the gossip that goes around is unreal,” he says.

Mizan eventually came forward and contacted Irvine, and they pored over the document together.

“We were kind of like, ‘Wow, we both know this is so wrong,’” Irvine says. “And then it kind of just spiralled out from there.”

Irvine decided to share the contract with other students and professors in the school’s faculty of gender and women’s studies and ask them what they’d do next. Someone suggested they post the document, with identifying information redacted, to the student union’s Facebook page to mobilize the student voice.

“More people needed to be aware of what was happening,” he explains.

Within an hour, the post caught fire, he says. Student comments, expressing a range of opinions — from shocked to angry to critical of the student union’s decision to publicly share the contract — rolled in fast.

Then local media started calling. Within a day, the story had gone national with stories from CBC, Vice, CTV News and more.

The headlines ranged from “Brandon University Sexual Assault Victims Forced to Sign Contract That Keeps Them Silent” to “This College Made Sexual Assault Survivors Sign a Gag Order or Be Expelled.”

“The phones were ringing off the hook,” Irvine remembers. “Everyone wanted to know what was going on.”

It didn’t take long for the university to react.

While one administrator initially defended the contract to CBC, within a few hours of mounting media scrutiny, the university issued a public statement. It not only acknowledged the existence of a behavioural contract — but conceded that its usage was “inappropriate” in cases of sexual assault and harassment.

“We want survivors to never feel silenced,” the statement said. “We encourage reporting in all cases.”

Lessons learned at Brandon

Two years later, the university is still working hard to better support survivors, a spokesperson says.

As soon as the university learned that its behavioural contract was prohibiting a survivor from talking about her experiences, administrators withdrew it and never used it again in cases of sexual violence, a Brandon University spokesperson told The Discourse in an email in May 2018.

While the spokesperson would not explicitly name Lisa Mizan, the email refers to a case “which gained widespread publicity in 2016” and “revealed gaps in Brandon University’s existing policy and procedures.”

The university has since worked to fill those gaps, he said. Brandon has now hired a full-time Sexual Violence Education and Prevention Coordinator; passed a standalone sexual violence policy and related procedures that aim to be “survivor-centred and trauma informed;” and struck a standing Sexual Assault Advisory Group to represent “a broad cross-section of the campus community, including strong representation from students, as well as faculty, staff and administration,” the spokesperson said.

Brandon is dedicated to “creating a culture of consent, to supporting survivors, and to preventing and reducing sexualized violence in all its forms,” he added.

Survivors can now, with the university’s support, “disclose their experiences at the time and place of their choosing, including anonymously or through a third party,” according to the spokesperson.

“In an era of #MeToo, when survivors’ voices have increasing power and draw increased attention, Brandon University is committed to ensuring all survivors are in the best possible position to make the best choice for themselves,” he added.

‘It was a very conflicting time’

Despite the improvements to Brandon’s policy, Mizan says there’s still work to do to incorporate the perspectives of survivors and other marginalized people in decisions about sexual assault on campus.

“Put more survivors at the table. Make this more survivor-centred, trauma-centred, Indigenous-centred, international-centred, LGBT-centred. Make marginalized voices louder,” she says.

“Because, on these tables, you know who I see? I see bureaucrats, I see people in suits, men who’ve never had to deal with sexual violence in their entire life. And I’m like, why are these men making decisions about what’s going to happen to my people?”

She acknowledges it’s sometimes hard for silenced people to advocate for themselves, but she knows their stories can make a difference.

“They’ve shut us down in such a way that it’s hard to speak out. But obviously, I think there are women who are ready to speak out. That includes me. So I think women like us should be the centre of this table — not the president of the university, not the V.P.”

Though Mizan was happy to see the university rescind its gag order, its removal didn’t undo her trauma.

“It was a very conflicting time. Like absolutely, I was very happy that I got my justice in the way that I did,” she says. But getting justice didn’t mean healing. “It came with a cost, and that was my life, because I almost killed myself over it.”

Still, speaking out changed her life, she says.

“That was an entire lifetime ago because I’m not the same person anymore. Then, I was a person who was silenced, pushed around, not believed,” she says. “I was really lucky that the university got called out. Other women don’t have that same story.”

She’s hopeful, though, because the #MeToo movement has held perpetrators accountable and amplified the perspectives of survivors. Mizan knows how important being heard is.

“My healing was that I spoke out.”[end]

[factbox]

Stefon Irvine’s tips for student empowerment

-

- Know your power as a student. “We, as students, we’re the consumer,” he says. “We have a lot more power than we perceive within the institutions we attend. So just knowing that in itself gives you a lot more power to stand up against institutions that are huge and bureaucratic.”

- Know the policies. “Know the policies and procedures of the university. It sounds really boring and tedious.” But universities will “try to tell you, ‘You’re breaking this policy, or this policy, or this official procedure and the ramifications of that are we’re going to expel you.’ So just know the policies you’re working up against.”

- Media can be a powerful tool, especially if the university seems unwilling to address your demands. “Write up a press release, connect with local media, send it out to national media and wait until the public gaze is on the university. You’ll be surprised at how quickly they want to band together with you to go through that list of demands and maybe more productively work through a solution.”

- Connect with people who can help. “Policies and procedures are not necessarily everyone’s cup of tea. So connect with faculty members, other students, other folks on your campus that share the same concerns and, where possible, the same political views as you.”

- Be proactive. “You don’t have to wait until somebody’s been gagged by an order. You can proactively get on top of it by looking at the other universities that have standalone sexual violence policies. Try to draft your own and submit it to the board of governors.”

- Record meetings. “We also have the right to audio record meetings.… Just know what you can do to give yourself some safety and to hold the university accountable for what they say.”

- Find an ally. “When you have to go to meetings, take a second person with you. It could be a student union rep, or a faculty rep who’s willing. We have this right.”

- Get to know your student union. “Generally speaking, a student union is there for the student and wants to help.”

[/factbox]

[cta]

The Discourse is documenting the impact of university policies and practices that silence survivors. Please consider taking our short survey and sharing your testimony.

The Discourse is documenting the impact of university policies and practices that silence survivors. Please consider taking our short survey and sharing your testimony.

[/cta]