Water and ecosystem health researcher Ed Kolodziej had observed the strange deaths of coho salmon in the lab, but standing in the Lower Duwamish River near downtown Seattle, this was the first time he had seen it in the wild.

Swimming in circles on the stream’s surface, mouth gaping, body twisting — the salmon was exhibiting symptoms associated with “urban runoff mortality syndrome” as it was then known, which had been seen by citizen science teams as far back as 1999.

It was the fall of 2017, and the University of Washington (UW) professor was tasked with investigating the mysterious deaths as part of a team of scientists from UW Tacoma, UW, NOAA-National Marine Fisheries Service and Washington State University Puyallup.

They had given their cell phone numbers to the network of citizen scientists who regularly monitored the urban creeks and streams in the Puget Sound area, with instructions to call if they saw a symptomatic fish.

With a testing kit and cooler at the ready, they’d jump in the car and rush to the scene to get a water sample as soon as they got the call, Kolodziej recalls.

“We were trying to get as close to the water that had started to kill a fish as possible,” he says.

The issue was significant — in some of the most-impacted watersheds around Seattle, it was estimated that up to 90 per cent of the returning coho salmon had died prior to spawning.

The affected watersheds pointed to a common denominator. Geographic information system (GIS) modelling from other members of the research team showed that the proximity of creeks to roads, the intensity of car traffic and weather patterns — such as a dry period followed by heavy rains — were some of the main factors contributing to these strange deaths, specifically of coho salmon

Researchers believed these deaths were due to some kind of toxicity from stormwater, but they needed to narrow it down to what, precisely, was causing the dramatic deaths — and why it was impacting coho specifically.

Of the thousands of chemicals detected in the retrieved water samples, they ended up discovering a group of 57 chemicals that were always present when the coho salmon died, says Kolodziej.

“Lots of them were chemicals that were associated with tires and tire rubber manufacturing,” he says.

One in particular — 6PPD-Quinone, the byproduct of an anti-ozonant added to the rubber to prevent cracking and wear in tires — proved to be particularly toxic.

“It got us thinking about tires as an important source of environmental contaminants,” says Kolodziej. “Tires are dumping a lot of contaminants out into the watersheds when it rains, and these are chemicals we should understand better, because they’re pretty darn abundant.”

In the broader Puget Sound area, it was estimated that approximately 40 per cent of the land area could be impacted by stormwater runoff tainted with 6PPD-Q, even as costly efforts to restore salmon habitat were underway on a significant level.

This spring, Kolodziej traveled to Vancouver Island University (VIU) to speak about his team’s discoveries and their groundbreaking 2020 study published in Science.

The yearly conference is part of a project that VIU’s applied environmental research laboratory has undertaken in collaboration with the BC Conservation Foundation, which brings together scientists, experts, environmentalists and salmon advocates to present their findings and discuss what to do next.

The research lab is also in the midst of conducting a large-scale study to understand where, when and how 6PPD-Q shows up in waterways on Vancouver Island that combines the work of local groups, citizen scientists and First Nations.

Discovering 6PPD-Q: A ‘trial by fire’

Jenifer McIntyre, researcher and associate professor at WSU’s School of the Environment and co-senior author on the Science paper, had been working to understand coho mortality for almost two decades when in 2017 she conducted a series of lab studies that demonstrated how a leachate solution made from worn tire particles was highly toxic to juvenile coho salmon.

Later that year, McIntyre again performed tests with the leachate on adult chum and coho salmon. The results were clear: all of the chum survived and all of the coho — typically a highly robust species that can withstand a remarkable amount of environmental contamination — died.

Once it was understood that coho were particularly sensitive, the task of McIntyre and the research team, which included Kolodziej, was to investigate what exact chemicals were present in the tire solution using a high-resolution mass spectrometer.

The tire leachate solution was separated into different portions based on their chemical properties and then tested methodically for toxicity.

Through this process, the team narrowed it down to a vial of four chemicals, and though the composition of these chemicals was understood, they were still stuck on nailing down the exact culprit.

Then Zhenyu Tian, an environmental chemist at the Center for Urban Waters at UW Tacoma and lead author, had a realization.

“It was just like ‘bing!’ in my mind. The killer chemical might not be a chemical directly added to the tire, but something related,” Tian stated in a 2020 release sent out when the Science paper was published.

After searching a list of known chemicals in tires that had a similar composition, Tian zeroed in on an industrial rubber paper from 1983 that talked about 6PPD, a chemical that protects tires from ground-level ozone.

A colourless and odourless component of smog, ground-level ozone is produced when pollutants react with sunlight and stagnant air.

It also breaks apart the bonds in rubber when exposed to sunlight. To combat these effects, 6PPD has been added to tire rubber since the 1950s.

However, during the process of interacting with ozone, 6PPD breaks down into a number of other chemicals, including 6PPD-Quinone — which had the exact chemical formula they were searching for.

The research team purchased some industrial 6PPD and replicated the process of ozonation that would happen in car tires and confirmed it had become the chemical compound they were looking for. The final step was to test it on juvenile coho.

Though 6PPD itself had some toxicity, they found it greatly increased once it was ozonated, and then increased again once they purified the 6PPD-Q out of the mixture, says Kolodziej.

“I mean, the coho were getting sick and starting to die in about an hour and a half,” he says. Not only had they nailed the correct chemistry, but they noticed the fish were also displaying the same twisting, gasping symptoms that he and other researchers had observed in the wild, and under the same timescale.

“This was a really exciting day for us… I mean, this was the trial by fire day. We were like, are we right on this thing or not? And they did die. And later that year, we published it all,” says Kolodziej.

Through this work and the subsequent studies conducted by other labs, experts settled on an LC50 measurement — LC meaning the “lethal concentration” that will kill 50 per cent of the exposed population in a toxicity test study.

The range was between 40 and 100 nanograms per litre.

According to their research and testing thus far in the U.S., 6PPD-Q is often present in roadway runoff near busy roads at levels of hundreds of nanograms per litre.

What is VIU’s role in local research?

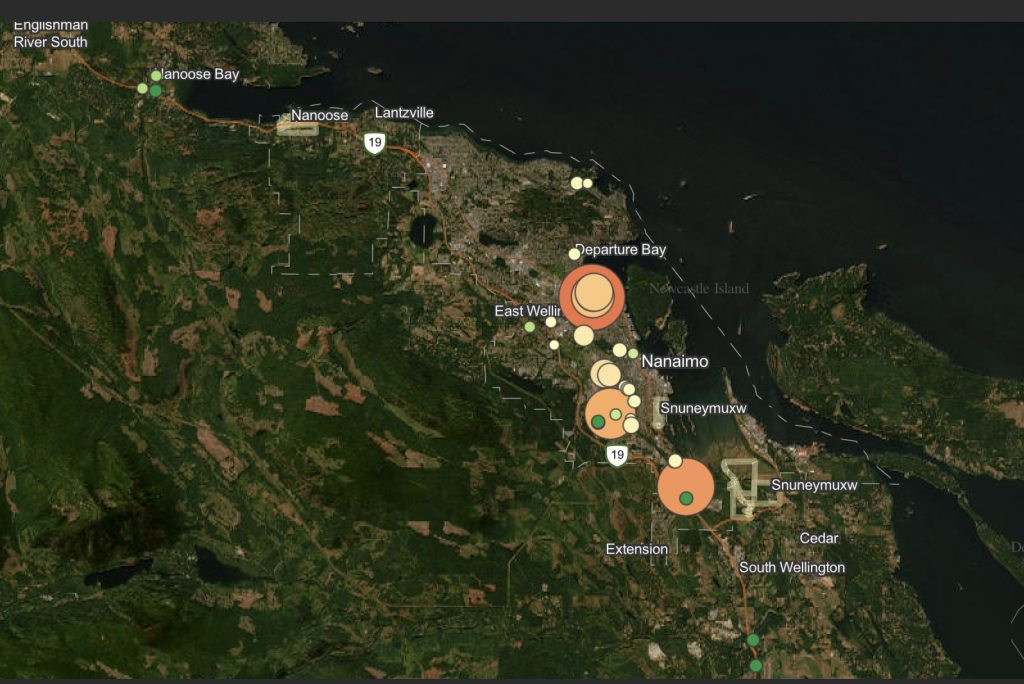

This year, VIU’s applied environmental research lab (AERL) is actively sampling 53 waterways in 99 locations between Victoria and Campbell River to compare samples before, during and after rain events as part of piecing together a picture of what’s happening in local waterways.

What they look for are the “hot spots” of small urban streams near busy roads, which also happen to be where coho often spawn, according to Dr. Erik Krogh, co-director of VIU’s AERL.

Thus far, the teams have detected 6-PPDQ in approximately 33 per cent of analyzed stream samples, with 97 stream samples measuring above the lowest toxicity limit of 41 nanograms a litre, and 36 stream samples higher than 95 nanograms a litre, according to biologist Haley Tomlin from the BC Conservation Foundation, who coordinates the sampling and spoke at VIU’s two-day conference.

In 2022, VIU teams detected 6PPD-Q in 10 out of 13 of the streams they sampled. Five of the 192 samples, including Northfield Creek, Millstone River, and Nanoose Creek, were registered as over the lethal concentration set at 41 nanograms a litre.

Crucial to the work is the involvement of a working coalition of 31 local groups made up of more than 150 volunteers that include citizen scientists, non-profit organizations and First Nations logging hundreds of volunteer hours.

Working together like this is especially crucial because Vancouver Island is full of different microclimates, which makes it hard to capture samples right when rain events occur, says Tomlin.

“We also lean on them a lot for the site selection, because they work in all these systems continuously so they know them the best,” she says. “They know what’s safe to access, but also where they can see the actual runoff coming into the system and see the impact.”

Once the samples are collected, they are dropped off at VIU, where the AERL has innovated a cheap, swift and highly sensitive method of chemical analysis using mass spectrometry that allows them to process up to 100 samples a day.

From there, the data is entered into an interactive map on an ongoing basis so results and current on-the-ground information can be shared with the public and accessed by all levels of government.

“Where we’re heading with this in the future… is to take the lab to the sample rather than bringing samples to the lab,” says Erik Krogh, co-director of VIU’s AERL.

To accomplish this, the AERL has developed a mobile mass spectrometry laboratory in a Sprinter van and this fall, the team plans to park it near roadways so they can make measurements in real time as the rains fall, says Krogh.

How does 6PPD-Q affect coho and other species?

Researchers speak about 6PPD-Q’s toxicity being in the range of nanograms, which is one-billionth of a gram — or the equivalent of one drop of water in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Every time someone buys a new set of tires for their car, if they weigh roughly 100 pounds, that means they contain about a pound of 6PPD mixed into the rubber, according to Kolodziej.

Its lethality at such low levels “suggests that 6PPD-Q is among the most toxic chemicals known for aquatic organisms, at least to coho salmon,” which ranks it “among a very small group of pollutants, mostly organo- phosphate or organochlorine pesticides, with acute toxicity expectations at tens of nanograms per liter,” states a paper written by Tian et al in 2021.

“It’s not a lot of chemical that’s killing fish acutely, within very short timeframes,” says Markus Brinkmann, the Centennial Enhancement Chair in Mechanistic Environmental Toxicology at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) and the director of its toxicology centre.

Right after the 2020 paper was published, Brinkmann says their team wanted to help out in any way they could, so he contacted Kolodziej to see what they could do.

“There clearly was a need to better understand how widespread the sensitivity to 6PPD-Quinone was, and what the mechanisms are that drive this,” he says, so they zeroed in on looking at why and how it affects some species of fish more than others.

“We were quite lucky, we had a couple of different species of fish in our aquatic toxicology research facility at the University of Saskatchewan at the time it came out, so we could basically start right away,” says Brinkmann.

Thus far, the USask research team have found that in addition to coho, there are varying levels of sensitivities in brook trout, rainbow trout and lake trout, dependent on factors such as age, concentration of 6PPD-Q and exposure time.

They found that the chemical also affects fish species in a number of ways, including dramatic spinal and jaw deformities, yolk sac retention and the development of edemas (fluid retention).

“We focus a lot on those acute lethalities but we tend to forget about those sub-lethal effects, right? Things that you can observe in fish before they actually start dying,” says Brinkmann, who also presented at the conference.

During his talk at VIU, he displayed a photo of the tail fin of a healthy rainbow trout.

“This is after exposure to 6PPD-Quinone — do you see all the blood pooling in between those blood vessels, where it shouldn’t be? This should be flowing right back,” says Brinkmann. “We sent this picture out to a number of fish pathologists, and they all tell us they have never seen anything like it.”

One area that needs further research is 6PPD-Q’s effect on the gill tissue of various sensitive fish species, as preliminary lab testing has shown that fish were transporting less oxygenated blood through their bodies. This could potentially account for the twisting, gasping behaviour displayed by affected fish, says Brinkmann.

During their testing on fish gallbladders, the research team also found evidence that suggested the lethality of 6PPD-Q might be connected to the fish’s capacity — or lack thereof — to rid the toxin from its body, a process generally known as toxicokinetics.

“Toxicokinetics might actually play a role here in those species’ differences in sensitivity,” says Brinkmann.

Another crucial finding of USask researchers was an unusually high number of dysregulated genes in exposed fish, roughly half of which directly correlated with the concentrations of 6PPD-Q the fish had been exposed to.

These dysregulated genes could potentially affect things like the fish’s immune system, inflammatory responses, and cell differentiation, development, says Brinkmann. “As well as cell death — basically, individual cells being triggered to die from this exposure.”

Is there a solution to dealing with 6PPD-Q?

Though researchers have yet to figure out a definitive answer on why 6PPD-Q is so lethal for coho, a coalition of researchers, environmentalists, community stewards and legal experts have joined forces to put pressure on the Canadian government to regulate the toxic substance.

The Canadian environmental law charity Ecojustice made an urgent request in February on behalf of Raincoast Conservation Foundation, Watershed Watch Salmon Society and Pacific Salmon Foundation that the federal government prioritize its assessment of the chemical.

“Globally, 6PPD-Q has been found in snow, soil, dust, drinking water and air,” states the letter sent by Ecojustice lawyers Daniel Cheater and Lindsay Beck. “6PPD-Q is also likely widespread in humans. It has been frequently detected in human urine samples and has been found to be ubiquitous in human digestive fluids.”

“Given the available scientific evidence,” the federal government will grant Ecojustice’s request, stated an April 30 response from Steven Guilbeault, Minister of the Environment and Climate Change.

“Before chemicals can be regulated, there first needs to be an assessment to prove that they’re toxic, and to prove that they’re harmful. So our request was essentially to jumpstart that process, put 6PPD at the top of the queue to be next assessed, speed up its listing under [the Canadian Environmental Protection Act] and get it regulated as quickly as possible,” says Cheater, who also presented at VIU’s conference.

The government is expected to publish its priority plan and timelines for assessments next summer, Cheater says.

In June, the U.S.-based Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set a screening value or maximum level for 6PPD-Q at 11 nanograms a litre “based on currently available science,” to support the protection of aquatic life from acute effects in freshwater streams and lakes.

Representatives in Washington and California have “undertaken formal processes that could require tire manufacturers to replace 6PPD in tires with one or more less-toxic chemicals,” reports the Puget Sound-based Salish Sea Currents magazine.

Most researchers agree that though there are highly effective mitigation strategies being innovated by universities like green infrastructure, living roofs and rain gardens, at-source changes to the manufacturing process of tires is the most crucial step in dealing with 6PPD-Q.

“As a chemist, I’d be really surprised if great alternative anti-ozonants don’t exist. We have some of the best chemists in the world. We can figure this out,” says Kolodziej. “We have an amazing amount of knowledge on how to do things like design a safe replacement anti-ozonant — if we choose to do so.”

Editor’s note, July 12, 2024: The article has been edited to also credit the NOAA-National Marine Fisheries Service as part of the team that discovered 6PPD-Q

Editor’s note, Aug. 1, 2024: The federal government is expected to release its priority assessment plan by summer 2025, not this summer, as previously stated.