Imogene Lim’s family has deep roots in B.C. Her grandparents lived in Cumberland and Vancouver’s Chinatowns and had to pay a discriminatory anti-Chinese head tax to enter Canada.

Now, she is one of the curators of a new exhibition at the Nanaimo Art Gallery titled Bleached by the Sun: Perspectives on Chinatown.

The exhibition features photographs from the Nanaimo Archives by Kin Jung, who lived in and documented Nanaimo’s third Chinatown from the 1930s through to the fire that destroyed it in 1960.

Over decades, Nanaimo has had various iterations of its Chinatown, which shifted through four different locations.

A research project on Nanaimo’s Chinatowns headed by Lim, who is a retired anthropologist, outlines the history of the various locations in Nanaimo.

The first Chinatown was built by the Vancouver Island Coal Mining and Land Company in the 1860s and was in the Esplanade and Victoria Crescent area.

Amid rising anti-Asian racism, the company moved Chinatown to its second location outside the city limits near what is now Bing Kee and View streets.

In response to rising rent in the second Chinatown, tenants formed the Lun Yick Company and raised money from 4,000 shareholders to purchase nine acres of land at Hecate and Pine streets, for Nanaimo’s Third Chinatown. However, the decline of the coal industry and impacts of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 lead to it becoming “increasingly derelict” and it was destroyed by a fire in 1960.

A fourth Chinatown, known as lower Chinatown, developed during the 1920s on Machleary Street.

The new exhibition at the Nanaimo Art Gallery takes the history of Nanaimo’s Chinatowns and places it in conversation with contemporary experiences of Chinese-Canadians today, who continue to experience anti-Asian racism. It includes photographs and multimedia artwork to help tell the story of Chinese heritage and the various Chinatowns of Nanaimo.

“I keep thinking Chinatown burned in 1960 and we’re in 2026,” Lim said. “Three generations have passed. So people who have arrived in the last decade, or even the past two or three decades, may have never known that Chinatown existed.

Kin Jung documented Nanaimo’s Chinatown through decades of photography

Jesse Birch, a co-currurator for the exhibit, said Kin Jung had multiple motivations for taking photos of life in Nanaimo’s Chinatown.

At first, he was unable to bring his wife Chan See to Canada due to the Chinese Exclusion Act. For 19 years he lived alone in Nanaimo and would take photos to share his life with her. He also worked as a stringer for news agencies reporting on Nanaimo.

Once his family joined him in Nanaimo, his photos “immediately started looking like everyone’s family photos,” Birch said.

“His work is just so important. Not only is it a record of a single person’s experience, but it’s a record of an entire community’s experience.”

One photograph in the exhibition is of a group of smiling Chinese women carrying a flag down a street.

Lim said she suspects the photo is from the 1940s during the Second World War and the women were using the flag to collect money for the war effort.

She said she has known about the photo for a decade and was initially drawn to it because of the Chinese women in the foreground.

“I was like, ‘Oh, wow, look at this. It’s exciting. There’s women in it. There’s this movement,’” she said.

It was only after she blew up the photograph that she noticed two Black women standing in the background.

“We basically have erased the black community,” Lim said. “We know very little [about it], and here is actual evidence of the community.”

Other photos in the exhibit include a photograph of former NDP Leader and Nanaimo MP Tommy Douglas in the cafeteria of Harmac, which Jung managed until he retired in 1974.

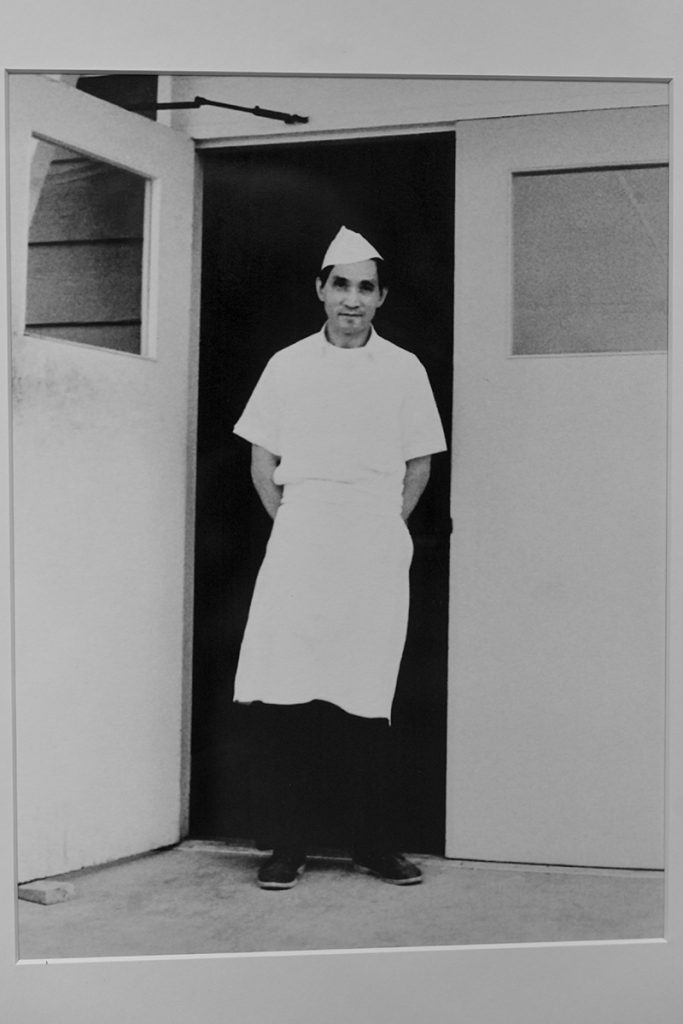

Another photo is what the curators call a “selfie” of Kin Jung standing in the doorway with his apron and cook’s hat on. This type of photo of himself, taken by someone unknown, is included alongside his original photos.

History in conversation with contemporary experiences

The exhibition also features a number of other artists whose works are put in conversation with Jung’s photos.

A number of the artworks feature coal and coal mining as central themes.

Jackie Wong’s Coal Mountain shows a pile of coal against a gold background, evoking the term “gold mountain” used by Chinese migrants to describe North America as a land of wealth and opportunity.

However, when they arrived in Canada, many Chinese men found themselves working in Nanaimo’s coal mines where they experienced long hours, dangerous working conditions and employers who wouldn’t even bother to learn their names.

This is depicted in Wong’s painting, Just Numbers, which uses the employee numbers of Chinese workers who died in the No. 1 Esplanade Mine Disaster in 1887 that killed 150 people, a third of them Chinese. The Chinese workers who died are only known today by their employee number.

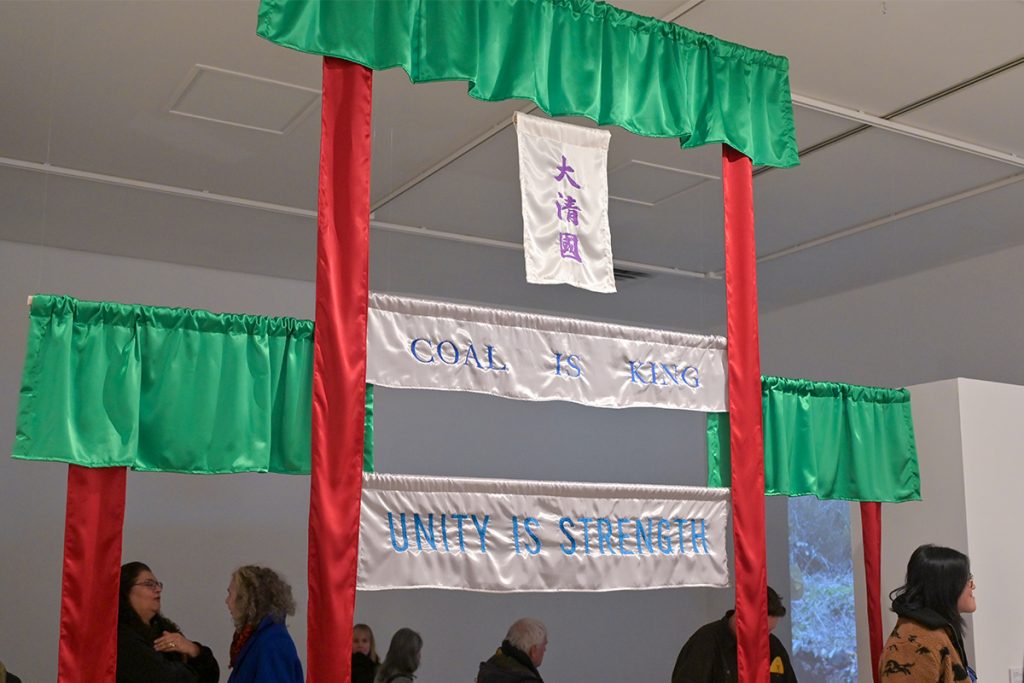

At the gallery, there is a fabric recreation of a Chinese gate with the words “Coal is King” on it. Patrons who walk under it are met with a screening of the film Pine Street, Now and Again by filmmaker Charlotte Zhang.

The film was originally commissioned in 2019 for the exhibit, Estuary. Zhang worked closely with former residents of Nanaimo’s third Chinatown to tell the story of Nanaimo’s Chinatown from the perspective of people who were living there instead of that of an outsider.

For this exhibition, Zhang went back to her original research from the Nanaimo Archives, including additional interview and unseen footage turning what was a “two-channel installation” into a new film.

As a first-generation Chinese-Canadian, Zhang said the experiences of Chinese immigrants who lived in Nanaimo before her “inform her existence in Nanaimo.”

“It’s very moving to work through those memories and through those narratives to understand my position here as well,” she said.

Anti-Asian racism from past to present

A hanging tapestry in the gallery by Karen Tam connects historic racism, such as the anti-Asian rioting in Vancouver in 1907 to ongoing anti-Asian hatred, which was brought to the forefront again during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

“You’ve got this juxtaposition of past and present and the violence between that community,” Lim said.

She also links anti-Asian racism of the past with today’s anti-immigrant sentiment.

“When they’re talking about immigrants taking away jobs, it’s racialized immigrants. They’re not talking about white immigrants,” Lim told The Discourse. “That’s the same thing that happened in the late 1800s and early 1900s. So in some sense, nothing has changed.”

Bleached by the Sun: Perspectives on Chinatown is on display at the Nanaimo Art Gallery until March 22 with lunchtime tours every Friday at noon starting on Feb. 6.