Since April 2022, the Nanaimo Area Network of Drug Users (NANDU) operated a site at 264 Nicol St. that helped about 200 clients a day with safe consumption, drug testing and overdose prevention.

The peer-run site garnered mixed community reactions, and on Monday, Jan. 16 city council declared the site a public nuisance after a report and recommendation by city staff following what Dale Lindsay, general manager of development services, said were repeated calls for police and city services to deal with on-site incidents.

Delegations to council highlighted concerns around off-property drug use and safety issues — like aggression, crime and impaired driving — with members after they had left the site.

After the declaration Nanaimo City Coun. Erin Hemmens told the CBC that as a former coroner, she understands the toxic drug crisis deeply and fully supports safe consumption sites.

She also said her decision wasn’t directly influenced by the community group opposition to the peer-run site, but this site in particular revealed a community-level struggle to balance the need for safe consumption sites with the quality of living for those living and working nearby.

Read more: Analysis: People living on the streets are struggling. Their neighbours are too

NANDU’s safe consumption site has now shut down, but misconceptions still linger, says Sarah Lovegrove, registered nurse and co-chair of Nanaimo Community Action Team (NCAT).

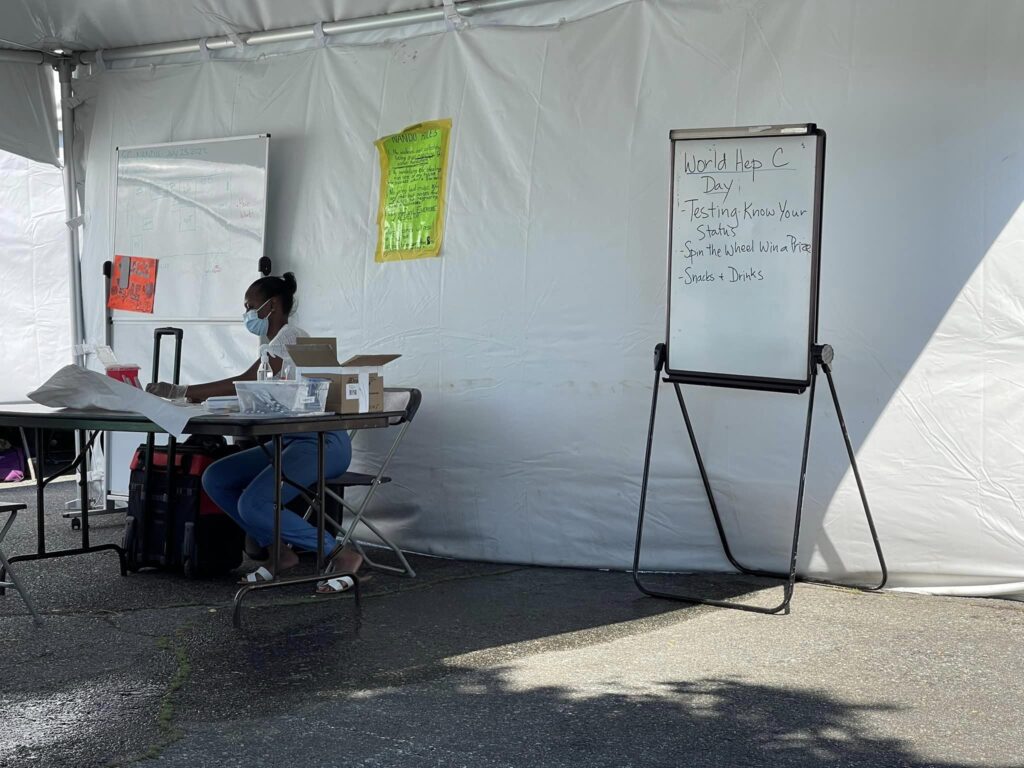

NCAT was created to bridge community-led projects focusing on drug use and mental health with provincial programs and supports. Lovegrove worked alongside NANDU and also provided first aid and wound care training for NANDU members.

To help us understand more about the situation from the perspective of mental health and substance use groups, The Discourse talked with Lovegrove about some of the most common misunderstandings regarding NANDU and peer-run safe consumption sites in general, and what information could help ease the division.

Each claim was confirmed on various social media threads by The Discourse reporters.

CLAIM: There’s no evidence that peer-run safe consumption sites work.

Fact check: False

While it can seem that peer-run consumption organizations and overdose prevention sites (OPS) are more recent responses to the opioid crisis, they’ve existed in Canada since the mid-1990’s in response to the HIV epidemic, and Canada’s first sanctioned safe consumption site opened in 2003.

These sites vary widely, but they generally offer supervised consumption services in simple, non-medicalized environments with support from trained peers. In response to the public health emergency declared in 2016, the number of safe consumption sites in B.C. was rapidly scaled up. The science around them is long standing and the federal government encourages their development.

The premise underlying these sites is harm reduction — a model that has evolved in Canada as early as the late 1950s as a way for people who use drugs to take control over rising death rates within their communities.

It focuses on removing as many barriers as possible to aid with the belief that meeting individuals where they are leads to higher chances of that person surviving.

In her research studying the development of overdose prevention sites, University of British Columbia’s Michelle Olding found that leadership and expertise from drug users themselves enabled “comprehensive, specialized, and collective practices” to emerge around overdose management.

That peer knowledge and support was a key factor in NANDU’s success in preventing overdose deaths, Lovegrove says.

Studies at the Society for the Study of Addiction and British Columbia Centre on Substance Use have found that peer involvement in consumption sites creates a more accessible environment for those wary of interacting with health and government institutions.

Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA)’s overdose prevention site at 250 Albert St. is run by health professionals, though it includes peer support and people with lived experience working alongside health workers.

Both sites have still been vital lifesavers, Lovegrove states. “There is no evidence of fatal overdoses ever occurring at a safe consumption site. That includes NANDU and the current OPS on Albert Street.”

(On March 7, the BC Coroners Service reported the first two deaths at OPS sites, one in 2022 and one in 2023).

One major difference between the two sites is the volume of clients and the level of resources.

CMHA’s overdose prevention site operations coordinator Destiny Herman tells The Discourse they have averaged 600 weekly visitors — an average of 85 people a day — though she notes those are not all unique individuals. The NANDU site served about 200 clients a day, and was largely volunteer-run.

“When you have volunteers providing a service as opposed to a designated site that has full time staff, it really contributes to the types of impacts that the neighbours have described,” said Dave LaBerge, manager of community safety for the City of Nanaimo, during the Jan. 16 city council meeting discussion.

With a local illicit drug supply often tainted with fentanyl, benzodiazepines, and xylazine and with fatal overdoses often happening when the user is alone and isolated, sites such as NANDU provided additional supervision and first-hand knowledge on how to respond to overdoses.

As the chemical makeup of illicit drugs continues to change, methods of intervention have also changed. Naloxone has been a proven aid in reversing opioid overdoses, but for overdoses involving tranquilizers and depressants (such as benzodiazepines), it is not effective, according to the BC Coroners Service review of toxic drug deaths, published last year.

“Lately, what people are seeing in terms of overdose is actually more sedation related to benzodiazepines. So [safe consumption sites] actually support people in coming out of that, or keeping them breathing, keeping them at least as conscious as they can be. Because there is no reversal agent that we can use in the community. So safe consumption sites keep people alive,” Lovegrove explains.

NANDU also provided inhalation spaces, a key safety factor as overdose deaths from inhalation rose from 31 per cent in 2016 to 56 per cent in 2020, the BC Coroners Service reported.

In the BC Coroners Service 2022 review, a focus on safe inhalation sites was listed as a provincial focus, since many safe consumption sites do not currently offer these services at all or to the extent needed.

The effectiveness of safe consumption sites, both peer-run and health organization-run, have been shown to decrease overdose deaths, reduce the number of ambulance calls and emergency visits, decrease the transmission of infectious diseases and improve access to other community services.

CLAIM: “The drugs are coming from NANDU”

CLAIM: “I heard that you can get whatever you want there when I was going into Dairy Queen which is right beside there some guy told me you can get even a pound of cocaine if you want”

Fact check: False

While there are some peer-run drug user organizations that can offer members a safer supply, such as Drug User Liberation Front in Vancouver, NANDU never had the resources and support to provide safe supply to their members.

“They’ve never participated in that. They’ve never offered any free or safe supply to anyone, any of their service users,” Lovegrove explains.

However, the BC Coroners Service review states that as tainted drug supplies continue to be a leading factor in overdose deaths, providing a safe supply is a first order of response to stop people from dying.

Currently, B.C. allows prescribed safe supply as part of a 2021 public health measure.

What NANDU did provide was drug testing for all who asked, which required samples to be mailed out to testing sites and results emailed or texted back to users.

NANDU also offered a possibly much more vital role in preventing overdose deaths: community support.

When asked about community claims on social media that NANDU was keeping their overdose stats at zero by dragging individuals in the middle of an overdose outside of the perimeter, Lovegrove countered, “If anything, they’re pulling people in.”

That attempt to bring users into the space meant NANDU often had to weigh the effects of members losing access due to violence or breaking rules when those members were the ones most needing the service.

“They had a number of people that they were trying to create better relationships with in terms of being able to access the space, and follow the rules, and keep everyone within the behavioral range,” she said.

This often means walking a fine line between allowing struggling members into the service but also retaining the ability to remove them if anyone’s safety is jeopardized.

A key factor of NANDU’s directive, and with peer-run support groups in general, is a focus on meeting individuals where they’re at, as opposed to holding unattainable expectations around who can and can’t access supports and services.

CLAIM: “They like this place because there are no rules and they are not monitored.”

Fact check: Partially false

NANDU operated as a peer-run members group. Those wishing to access NANDU and their resources needed to become a member, and that meant agreeing to NANDU’s rules, posted outside the site. These included noise restriction, removal if unable to comply and other safety measures.

Members using the site were required to halt all activity and place supplies on the table when a nurse, support worker, or RCMP entered, Lovegrove explains. “Everyone drops what they’re doing. No one smokes, no one injects. No one even really moves. Everyone just kind of leaves all their supplies on the table to ensure the safety of the people coming in and out of the tent who aren’t users.”

Nursing support was not able to be on-site at all operating hours, but medical aid was provided by peers on-site who were given medical supplies from Island Health and wound training from nurses such as Lovegrove. And Naloxone was readily available for when overdoses required it.

“People operated under the Good Samaritan Act, which allows individuals to administer Naloxone to anyone experiencing a fatal overdose. And that is a part of the public health mandate from the federal government,” says Lovegrove.

NANDU was also able to connect members with housing services, social services and warming shelters provided in town. Island Health’s primary care outreach van connected with the site at least once a week, providing supports and connections to medical aid.

“It’s just a safe space for people to go, rather than using in isolation,” Lovegrove says.

CLAIM: People who use drugs do not have a quality of life worth saving.

When asked what myth she comes across the most, Lovegrove points to the false assumption that safe consumption sites do not save lives, or worse — that those using the sites don’t deserve to be saved.

This sentiment can be attributed to viewing addiction as a personal failure, when in reality many factors contribute to problematic substance use, including those outside of a person’s control, like acquiring an addiction to prescribed drugs following an injury, or enduring childhood trauma.

This viewpoint can also create shame, which in turn makes people who use drugs less likely to seek help and more prone to use alone, increasing their risk of overdose.

In addition, people tend to attempt recovery from drug or alcohol addiction two to five times before they are successful.

A 2021 study by the University of British Columbia showed that after the expansion of OPS sites started in 2016, participation in addiction treatment increased.

“It was just heartbreaking to imagine that people don’t understand how many lives are actually being saved in these spaces,” Lovegrove says. She notes that comments on social media claiming that users don’t deserve help eventually led her to deleting her personal accounts as a way to save emotional energy needed for supporting community users.

“Just because people perhaps only perceive it to be a certain demographic of individuals, perhaps those lives don’t matter to them. I’m not sure. But there are a significant number of lives being saved simply by the presence of these overdose prevention sites.”

March 8, 2023 Editor’s Note: This story was updated to include new data from the BC Coroners service related to overdose prevention site deaths.