Growing up along the Highway of Tears in Lax Kxeen (Prince Rupert, B.C.) on the territory of the Smalgyax-speaking peoples, Lugil Wilaaysm Hanaa (Hyla McQuaid) said she has seen first hand how the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls persists in Canada.

“I’ve seen family go missing, I’ve seen friends — I’ve seen everything,” said McQuaid, who is Ts’msyen (Tsimshian) and X̄aʼislak̓ala (Haisla) and belongs to the Laxgibuu (wolf clan). McQuaid is also the Indigenous students’ representative at the Vancouver Island University Students’ Union.

When McQuaid was 16, her older sibling went missing for a night.

“The first thing I thought of was Tamara [Lynn Chipman], who went missing at 22. Her story shaped my entire life,” McQuaid said. “She went missing at 22, at the same time that my mom was 22.”

McQuaid said her sibling was around the same age when they went missing.

“I was thinking how scary it’s going to be when we find my sibling if they’re dead, or how scary it’s going to be if we never find them.”

When the family called in the missing person’s report to police, they were asked if McQuaid’s sibling was Indigenous.

“We decided as a family that we’re not going to tell them that they’re Indigenous,” she said. “I think that hiding our Indigeneity for any reason — and especially for a reason of survival — is an issue that happens a lot without us speaking about it.”

Over the next eight hours, the family mounted a search for McQuaid’s sibling. She said her sibling was found the next day but that she felt the police lacked the training to handle the situation.

McQuaid said the issue also affects Indigenous men.

“Indigenous men face extreme ramifications of colonialism through their gender,” she said. “It’s not just Indigenous women who are going missing.”

When people go missing in her community, McQuaid said she rarely works with police and usually searches alongside family members.

“I’m always working with someone’s auntie, with someone’s grandma, with someone’s dad, and I think that that needs to be highlighted,” she said. “Not only the emotional stress, but the labor that goes into making up for what the police aren’t doing.”

This year, McQuaid and the VIU Students’ Union is also organizing the No More Stolen Sisters Memorial March on Snuneymuxw territory (downtown Nanaimo) on Friday, Feb. 13, in alignment with the national Sisters in Spirit movement. It will bring together Indigenous leaders, community members and allies to “honour the lives of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQIA+ (MMIWG2S+) people” and also “affirm the inherent rights, dignity and safety of Indigenous women, Two-Spirit and gender-diverse people.”

As the march weaves through downtown, it will also pause for a moment of silence outside Evolve Nightclub, where Lisa Marie Young was last seen before going missing in 2002.

“I know that there was a great turnout last year. And I think that this issue is becoming more and more visible in the community,” McQuaid said.

Calls for justice

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls website says “First Nations, Inuit, and Métis women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people live with an almost constant threat to their physical, emotional, economic, social and cultural security.”

The final report from the inquiry, released in 2019, documents testimony from survivors of violence and family members and adds context to the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous people. It notes that factors such as intergenerational trauma, marginalization, housing insecurity, employment and health care barriers, lack of cultural support and colonial and patriarchal policies all contribute to the issue and leave Indigenous people to be vulnerable to violence.

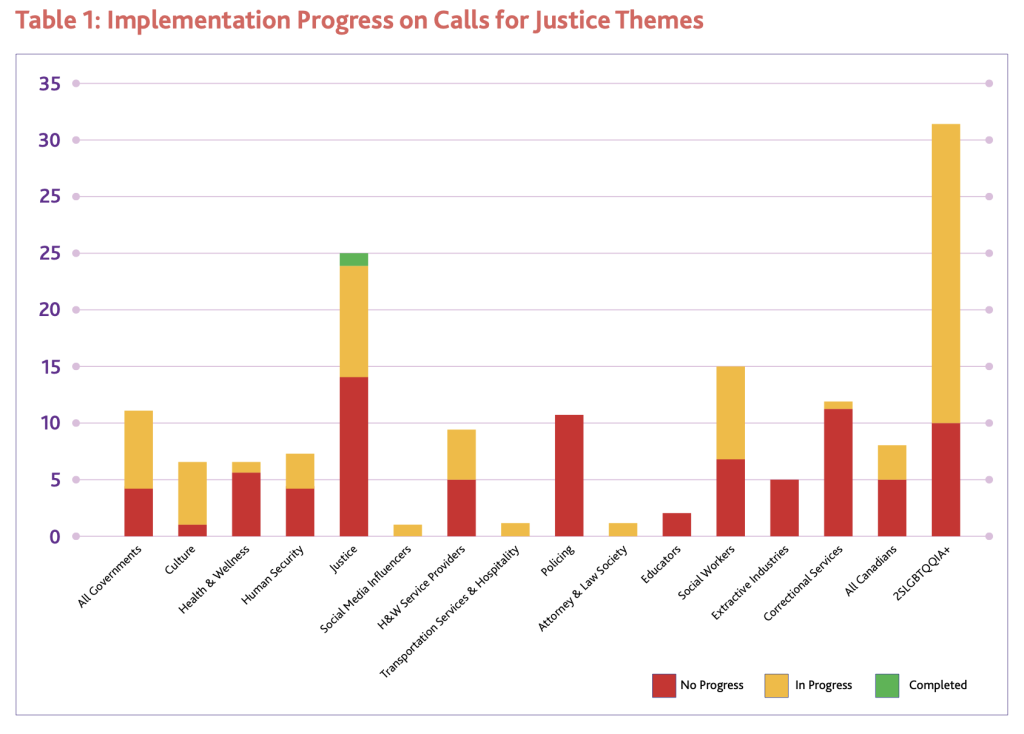

The inquiry also released 231 Calls For Justice along with the final report, providing a path forward “to end and redress this genocide.” The calls explore four pathways that address “historical, multigenerational and intergenerational trauma; social and economic marginalization, maintaining the status quo and institutional lack of will and ignoring the agency and expertise of Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people.” The inquiry says these Calls for Justice are not optional.

Each year, the federal government releases the Federal Pathway Annual Progress Report, which outlines actions taken under Canada’s National Action Plan for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people. While the report offers key highlights of steps the federal government has taken in response to the Calls for Justice, there is no concrete number offered to reflect which calls have been implemented in full.

A 2024 progress report from the Assembly of First Nations noted that two of the 231 Calls for Justice had been fully implemented by the federal government at the time.

“This reality indicates that many of the initiatives and programs being reported by all levels of government that ‘assist’ in addressing and supporting the 231 Calls for Justice are mainly existing programs and funding initiatives framed to appear as substantially and meaningfully accomplishing the [Calls for Justice],” the report says. “There are also a number of initiatives that began as a response to the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action that are now framed as responding to the Calls for Justice without using a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ Peoples (MMIWG2S+) lens.”

It calls on institutions such as governments, police forces, courts, hospitals and the criminal justice system to review their practices and policies and “uncover their built-in systemic biases against First Nations people and commit to making real substantive change.”

The Assembly of First Nations also released a progress report in 2025 focusing on what it calls “the growing crisis of human trafficking impacting First Nations women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people.”

After listening and learning from survivors and their families, the assembly says it chose to highlight human trafficking as a key theme in this year’s report. It says this violence is rooted in a legacy of colonialism, racism and systemic inequality and that it is not new.

“The report shows that responses to trafficking remain underfunded and inconsistent across sectors and regions,” National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak said in a 2025 press release. “Survivors and families are excluded from decision-making, and community-led solutions lack sustainable funding.”

McQuaid said she would like to see safe transportation options for Indigenous people in remote communities.

“It’s really unfortunate that getting from one place to another is dangerous for anyone,” she said.

“Once they took away things like the Greyhound, our travel got a lot more difficult and with that, hitchhiking became more prominent,” she said. “That’s our government putting us in vulnerable positions by not prioritizing safe transportation for people.”

‘The issue impacts everyone,’ march organizer says

The No More Stolen Sisters Memorial March will start with a gathering at 3:30 p.m. on Friday, Feb. 13 in Diana Krall Plaza. At 4 p.m. it will proceed through downtown to Maffeo Sutton Park.

McQuaid said the Vancouver Island University Students’ Union is organizing the march with the help of the Indigenous Studies Club at VIU and family and friends of local missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

A sign-making station will be at Diana Krall Plaza and the event will open with a blessing by an Indigenous Elder before the march. When the march ends at Maffeo Sutton Park, there will be speakers and an Indigenous food truck.

“It’s an issue that impacts everyone,” McQuaid said. “It’s your neighbours, it’s people in the community. I think that what people don’t understand is that this isn’t just affecting Indigenous peoples, this affects a wide range of the population.”

With files from Shalu Metha.