This story is the final part of our series on homelessness, housing and mental health in downtown Nanaimo. Read part one here. Read part two here.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter for local news that uplifts, straight to your inbox.

For Chrissy Forsythe, running her Delicado’s deli on Wesley Street these days means being constantly vigilant.

She first noticed people starting to camp down the road a few years ago, not long after an overdose prevention site moved into the basement of the supportive housing complex there.

At the time, she says she did her best to be supportive, taking food out to everyone twice a week for about a year until it became unaffordable.

When the pandemic shutdown hit, the numbers of tents increased dramatically, according to Forsythe — and so did the chaos on the street.

“I had somebody overdose in the bathroom about a month and a half ago. It’s constant, right? I can’t even let people in here to use the bathroom anymore,” she says.

“One guy I pulled out, he was shaking on the floor so I dumped some water on his face because I didn’t have any Naloxone in here. And finally he came to, and I was screaming at him and shaking him, and it’s COVID, I’m not even supposed to be touching anybody. And there’s people all over in here, it’s the middle of lunch, and I’m dragging him out of the bathroom with his suitcase. It’s crazy.”

Forsythe says she’s done her homework on the issue and feels confident in saying that the community is now at the breaking point.

“It’s every day. People just don’t understand that. It’s an everyday event. And as much as I have compassion for these people there needs to be some other support systems in place that takes the pressure off of the general public,” she says.

Housing and mental health advocates have made clear what’s needed to get ahead of the crisis, from providing housing first to more streamlined access to detox and other mental health supports. But as various levels of government continue to struggle to respond, the community has taken action in a variety of ways.

Local business owners like Forsythe have banded together to maintain cleanliness and respond to safety concerns downtown so they can get back to business. Other organizations like the Nanaimo Aboriginal Centre are working to prevent chronic homelessness by connecting with youth.

Meanwhile, some people living on the streets say that in the absence of housing and other supports, there is safety and a sense of community in camps and displacing them only makes things worse, as a minority of residents have resorted to vigilante evictions and even violence against them.

A coordinated response

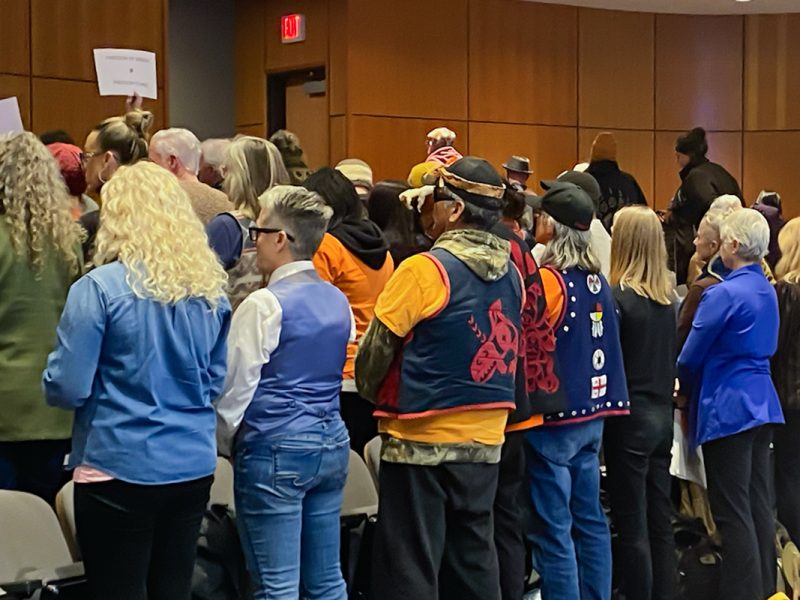

Earlier this year, the City of Nanaimo’s health and housing task force, the Nanaimo Homeless Coalition, and United Way Central & Northern Vancouver Island brought together more than 200 stakeholders to identify solutions. They said that among the key approaches needed was streamlined intake and assistance for people experiencing homelessness and mental health issues in order to navigate the complex web of disjointed community supports.

In response, Nanaimo’s Homeless Coalition is accepting proposals to develop an Integrated Coordinated Access system modelled from successes in cities like Calgary, Alta. and Abbotsford, B.C. that centralizes referrals to various community programs so that people can access help more quickly and avoid bureaucratic inefficiencies like being placed on multiple waitlists for similar services at the same time.

Meanwhile on Wesley Street, the Old City Quarter Business Improvement Association has partnered with the city on a pilot project to tackle some of the issues the camp of 50 to 100 people has caused for the neighbourhood and local businesses.

“I guess there’s the point of view that you can complain and say that someone else should be doing it, or you can take some chances, get off your ass and try something,” says Darren Moss, co-owner of the Cardea apartment complex in the area and a member of the business improvement association.

Moss, along with other property owners in the area, leads the jointly-funded pilot project, which is called Community Connect. It started over the summer and focuses on “rebuilding pride of place and providing some increase in safety and cleanliness,” according to Moss.

The way it works is that people call a number, any time of day or night, that then goes to a call centre to dispatch a safety patrol. Daily cleanup crews have also been implemented to maintain a constant presence in the area, but also to gather data and understand the issue better so they can look towards future solutions.

“I think what we’re finding is that the city and other bodies at a government level have a hard time getting things moving really quickly because they have more inertia and more public outcry. And so we can’t just say that they ‘should’ fix it, because they’re trying hard, and they have a lot of great initiatives going. But they can’t do it on their own,” he says.

“I think most business owners don’t feel that way, they feel that it’s a municipal, provincial and national challenge and it’s up to those levels of government to find the solution. But I think it takes collaboration between all those different groups to find some long-term solutions.”

Reaching out to youth

The City of Nanaimo’s five year action plan to end homelessness, released in 2018, points to the need for more early interventions before people become habitually homeless, especially for youth, and the need for more culturally specific services for Nanaimo’s diverse Indigenous population.

Another initiative focused on the Wesley Street area aims to do just that. The Mobile Youth Outreach Team was started in March by the Nanaimo Aboriginal Centre’s youth advisory council, whose members are all currently in government care.

Every week, the outreach team goes to the Wesley Street area to offer toiletries, food, blankets, harm reduction supplies, journals and books to homeless youth, with funding from the City of Nanaimo’s Community Action team and in partnership with Literacy Central Vancouver Island.

Almost 39 per cent of the homeless people surveyed in March reported that they had first experienced homelessness while under the age of 25. Approximately one-third of respondents identified themselves as being of First Nations, Métis or Indigenous ancestry, though they represent just six per cent of the general population of Nanaimo.

This month, the Nanaimo Aboriginal Centre gave their youth outreach program a boost with a new 24-foot RV that is capable of meeting youth and offering supplies and support wherever they are, instead of expecting them to find their way to the service providers, says Joel Harry, director of program development.

“We’re not saying this is supposed to solve youth homelessness, we know that we can’t do that. But we do want to do as much as we can,” he says. “The core value of this service is to provide youth with basic-need items and to maintain optimal health and wellness through housing and security, but also to develop and maintain those relationships in the community.”

Lack of hope leading to citizen evictions

Still, as the number of people experiencing homelessness in Nanaimo has increased by an estimated 200 to 300 per cent in the last four years, some frustrated residents have taken even more direct action.

In February, approximately 40 to 50 residents cleared out an encampment on Hill Road in South Nanaimo that was on private property, with the permission of the property owner.

“We have been victims long enough as the crime levels and invasion on our community had reached [a] breaking point,” local resident Greg Stolz wrote in a social media post about the eviction of what he calls a “camp of rats”. “With little or no support from the legal system, mental health care or addiction treatment we felt we had no alternative [but] to take matters into our own hands.”

Just a week later, another group of residents in the north end of the city removed a camp on crown land across from the Woodgrove Centre shopping mall.

Prior to the construction of two temporary modular supportive housing sites on Terminal Avenue North and Labieux Road in 2018, the city had an estimated 60 encampments scattered throughout the city, according to Nanaimo RCMP. Today, they estimate there are between 30 and 40, with the north end of the city experiencing increased pressure.

Clint Smith, a mechanic who lives in Lantzville, estimates that he has participated in or organized 20 to 30 community removals of encampments and evictions of nuisance properties in the last year, including the one by Woodgrove.

Motivated by what he describes as increasing crime levels in Lantzville and the north end of Nanaimo, he started the social media hashtag #takebackourcommunity to help organize local people online, and frequently posts to a popular Facebook group called Thieving Nanaimo.

“What that hashtag is meant to do is to empower each individual neighbourhood to look after their own individual neighbourhood concerns. Because of that, many more blockwatches and many more organizations have sprung up around the city,” he says.

Smith then speaks with the individual groups planning their particular cleanups and advises them on how to deal with issues like needles, garbage, or aggression, and how to work with city bylaw officers, the RCMP and the media.

The emphasis is to try and keep things positive and compassionate, says Smith.

“Nobody I have come across ever in any of this work has an appetite to kick somebody who’s already down just because they’re down,” he says. “Maybe they’re just somebody who’s down on their luck and is transient on their way from one place to another. […] So I’m trying to spread a little bit of empathy, but stand firm and don’t let your neighbourhood get overrun.”

By organizing neighbourhood cleanups and harassing the problem makers, “the problem will wind up where it needs to be, in the public eye, ” Smith writes in a Facebook post. “So provincial, local municipal, legal, etc. are FORCED to deal with it.”

City bylaw manager Dave LaBerge says that they have encouraged people in more public spaces and visible encampments to instead take overnight shelter in local parks where they are permitted, rather than private property, and recognizes that the situation “is not sustainable for us, or the police, or quite frankly for the people who live around that area.”

However staying in a park isn’t a realistic option for Renee Mayers, who resides in the Wesley Street encampment where she says they have formed a community of people who are accountable to and look out for one another.

“We care about things. So for safety, I feel perfectly safe here. I would not feel safe going to one of the parks they’re trying to get us to go to,” she says. “I don’t know what other strangers we’re going to meet out there, and there are people going around burning down people’s tents. Vigilantes. People who are supposed to be the good people.”

Vigilante actions

Tension over homelessness in Nanaimo is nothing new, but has intensified as the numbers of people without homes rises.

In the summer of 2018, frustrations from those both in support and against Discontent City, a large encampment on an empty lot in Nanaimo’s downtown, boiled over into a confrontation on August 5.

A rally organized via a Facebook page called “Action Against Discontent City”, was attended by the Soldiers of Odin, an anti-immigration vigilante group who claimed that residents of the city had “asked them to come,” according to a media report at the time.

Though the street in front of the camp was blocked for several hours, the day ended without arrests or assaults. However the event illustrated the increased tension in the community over the issue.

Last fall, two people in Nanaimo were attacked with baseball bats as they slept in their tent. One of the victims says he was threatened and told to “get out of town.”

“We get fireworks thrown in at us. They light them and throw them in,” says Mayers. “They shoot paintballs at us, they throw water bottles and shit at us. It’s pretty gross. And again, that’s judgement, right? [They] don’t have a clue.”

In the Nanaimo Homeless Coalition’s recent design lab on solutions to the crisis, participants called for better education around the trauma associated with homelessness and the need to humanize the experiences of people living on the streets.

Jen McMillan, who also lives in the Wesley Street camp, says she’s been sprayed with a fire extinguisher several times. “People will stop, looking like they’re going to ask for directions or something and spray me with a fire extinguisher. How is that helpful? What exactly do they think they’re going to accomplish?” she says.

The Nanaimo RCMP’s position is that they do not endorse the neighbourhood evictions or the violence, but recognize it’s a significant community issue. They seek to remain impartial but not neutral, says Nanaimo RCMP spokesperson Gary O’Brien, with a primary role to keep the peace and make sure no illegal actions such as violence take place.

“There’s going to be a continuous pushback, and I hear that from neighbours and residents all the time,” says O’Brien, whose detachment has attended evictions in Cedar and several in Lantzville.

“They’re not going to accept that they are sharing their neighbourhoods with homeless people. And we understand that. We do. Because three years ago they didn’t have to share their neighbourhoods with people who couldn’t find homes. Now, it’s in everybody’s sight.”

As a former property manager in Nanaimo, Mayers says she knows many of the people in the camp because she both rented to and evicted some of them, and realizes the challenges associated with getting people housed and why it’s frustrating. But everyone has a story of how they ended up here, she adds.

“My mom passed away a few years ago and it threw me for a loop. That’s why I’m here. I haven’t worked since. My dog has major separation anxiety, I can’t go anywhere without him,” she says.

“Understand that we are people. We’re looked upon so negatively. Not everybody down here is a junkie. Not everybody down here is here because of drugs. And for those that are, so what? Don’t judge them. You don’t know what happened to them prior to them becoming a drug addict.” [end]

This story is part three in our series on homelessness, housing and mental health in downtown Nanaimo. Sign up to receive updates on our reporting straight to your inbox.