Editor’s note, Sept. 27, 2023: At the time of publication, this article did not adequately include the circumstances surrounding Taiaiake Alfred’s resignation from the Indigenous Governance program he founded at the University of Victoria. Students alleged psychological harm resulting from a culture of toxic masculinity in the program, and enrollment was suspended for the 2018-2019 academic year after a third-party review. Taiaiake spoke to these circumstances in his hour-long interview with The Discourse, and this article has been updated to include some of that context. We regret the omission.

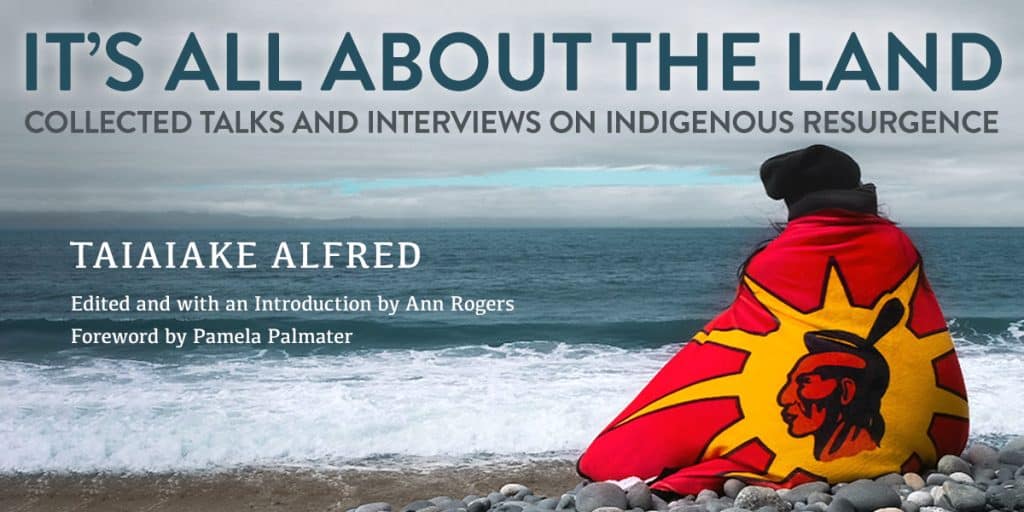

Any discussions about truth and reconciliation that don’t centre land, systemic change, and compensation for past harms are inherently problematic, says Kahnawà:ke Mohawk activist, writer and scholar Taiaiake Alfred. His new book, It’s All About the Land, is a collection of some of his best speeches, interviews and lectures over the last 20 years.

As the founder of Concordia University’s Native Student Centre and the University of Victoria’s Indigenous Governance Program — he stepped away from that role in 2019 — Taiaiake’s work focuses on the resurgence and revitalization of Indigenous political systems and the restoration of ancestral land-based cultural practices, among other topics.

The book critiques notions of reconciliation that have “allowed Canadians to continue to do these ineffective things and maintain themselves in positions of authority and ownership and power that are exactly the same as in the colonial period — exactly the same as in the ten years before they started doing reconciliation,” Taiaiake tells The Discourse. “So who does reconciliation benefit? It really only benefits the white settler society.”

For his fourth book, Taiaiake teamed up with author and former Vancouver Island University professor Ann Rogers to edit the collection. The book describes how the Canadian government’s reconciliation agenda is “a new form of colonization that is guaranteed to fail,” and carries an urgent message “that Indigenous peoples across the world face a stark choice — to reconnect with their authentic cultures and values or continue following a slow road to annihilation.”

The book’s concept emerged somewhat organically when Rogers was working on an unrelated project about national security issues, she says. She requested an interview after she became interested in Taiaiake’s writings on warrior societies.

However the more Rogers read and listened to Taiaiake’s work, the more engaged she became in his thoughts and ideas, and describes the process of going through his speeches and interviews as a transformational journey.

“Looking back now, it was just that extractivist, ‘I need this part for my work,’ right? And I was just so ignorant,” she says with a chuckle. “It was quite a long process, I guess it was three or four years that I was looking at the material. And I started as a complete neophyte. I was so naive, and looking back now, it’s hard to remember that. But I think the lesson I got from it was the importance of personal decolonization and that personal work.”

Taiaiake says he also learned a lot in the process of going through decades of material and looking at how his ideas and politics have both shifted and stayed the same over time.

“I think my ideas have been pretty consistent. So the whole purpose and intent of doing what I do, and the fundamental message about what we need to do to really gain some justice in this country has been consistent. But definitely my style, temperament, manner and vocabulary has changed over the years,” he says.

“When I started off, I [had] a young warrior mentality, coming to disrupt and coming to battle against colonial forces. And there was a need for that.”

Over the years, that mentality shifted, Taiaiake says. “I don’t want to say [it became more] conciliatory, but different. My function has been to try to bring people together. Unifying our people as opposed to fighting with outsiders.”

In 2018, CBC News reported that the University of Victoria’s Indigenous Governance Program, led by Taiaiake, would suspend admissions for a year after a third-party review found evidence of “dysfunctional classroom dynamics” that left students traumatized. Students reported to reviewers that there was “little tolerance for LGBTQ and two-spirited individuals” in the program. The emotional and psychological impact on students was “profound,” according to the review.

Taiaiake resigned from the program in 2019.

“At a certain time in my life, I embodied a toxic masculinity,” Taiaiake says, reflecting on it now. At first, “it wasn’t problematic; it was celebrated.”

Taiaiake, who used to be in the U.S. Marine Corps, says the program was designed like a bootcamp, to train warriors.

The idea was that “we’re going to train you to be the kind of leader that can withstand the struggle in the battle, and to engage in a very hostile environment. And I was perfectly suited for that,” he says.

“I’m gonna acknowledge that, yes, some people were harmed in it,” says Taiaiake. “But I’m also not going to write it off as something that should have never happened, right? It was a time and a place. And it served a great utility. I don’t do that now, because I believe I have a different role and a different mission now.”

One lecture included in the book is The Psychic Landscape of Contemporary Colonialism, which Taiaiake delivered at the University of Ottawa in 2011.

Developed in the wake of his work with the Mohawks of Akwesasne to hold major corporations accountable for their contamination of the natural environment, he spoke about what he came to understand regarding the psychic aspect of the struggle that Indigenous people are facing. He realized that “the cure for the colonial disease is the restoration of land-based cultural practices and reconnecting the generations of our people to their homeland in cultural, spiritual, and physical ways,” he writes.

Another talk, Reconciliation as Recolonization, given at Concordia University in 2016, looks at how many Indigenous and non-Indigenous people have a widespread dissatisfaction with reconciliation — that it seems “hollow and ineffectual given the seriousness of the crimes that have been committed against us,” and that the Christian roots of reconciliation “shapes the whole enterprise.”

Reflecting on those themes, Taiaiake says “Indigenous people are sick of hearing about reconciliation and land acknowledgements unless it’s directly tied to some sort of action on the part of the government or whoever’s offering those land acknowledgments to make some real, systemic changes and not just acknowledge the harms of the past without doing anything about it.”

A lot of Indigenous writing and thought has become somewhat de-politicized, Taiaiake says — less about encouraging people to act against and confront colonialism and systemic injustice, and more centred around themes of reconciliation and healing.

And though it’s good for people to be working through these issues and dealing with their traumas, “people are recognizing that the philosophy, the philosophical, the strategic, the political, has been edited out of our movement. And so this brings it back,” he says.

Additional book launch events will take place Wednesday, Sept. 27 from 2 to 4 p.m. at the Salish Sea Market in Chemainus, on Wednesday, Sept. 27 from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Ladysmith Museum and on Saturday, Sept. 30 from noon to 2 p.m. at Volume One Bookstore in Duncan.